Geo-Historical Sleuthing: New Jersey Edition

- Submitted on

- 4 comments

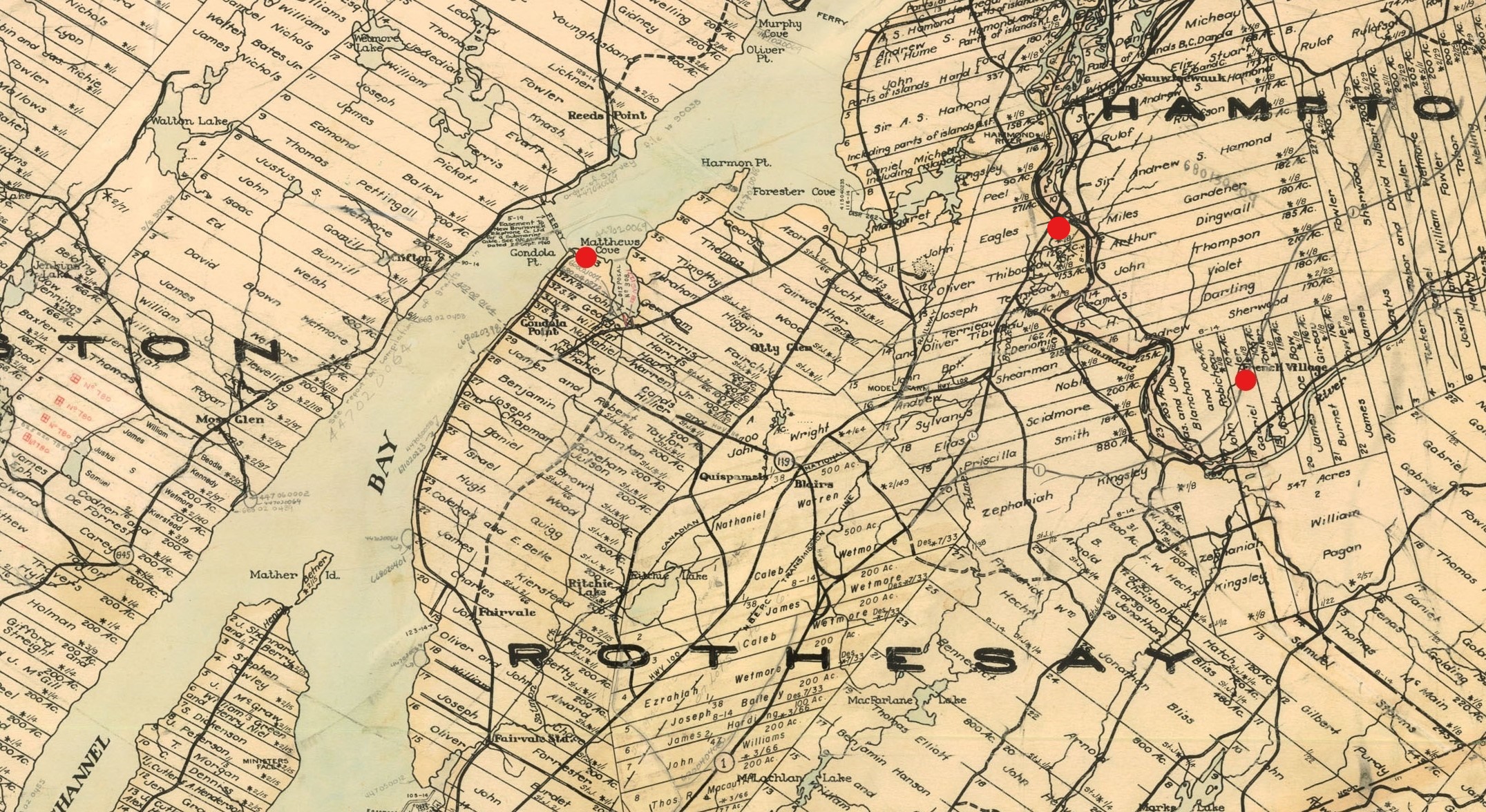

How do you go about locating where a person lived 240 years ago in a place you’ve never been? This was my situation when I started researching New Brunswick loyalist, Gasper Maybee, who was originally from Bergen County, New Jersey. Through using a series of modern and historical maps, first-hand accounts, and some very helpful local expertise, I was able to pinpoint the area where he grew up and inherited land.