- Submitted on

- 0 comments

Loyalists who tried to return home at the end of the American Revolutionary War often faced the threat of violence. Daniel Babbit was one of those Loyalists. He was left so frightened by his experience, he chose to leave the country rather than risk his personal safety by remaining.

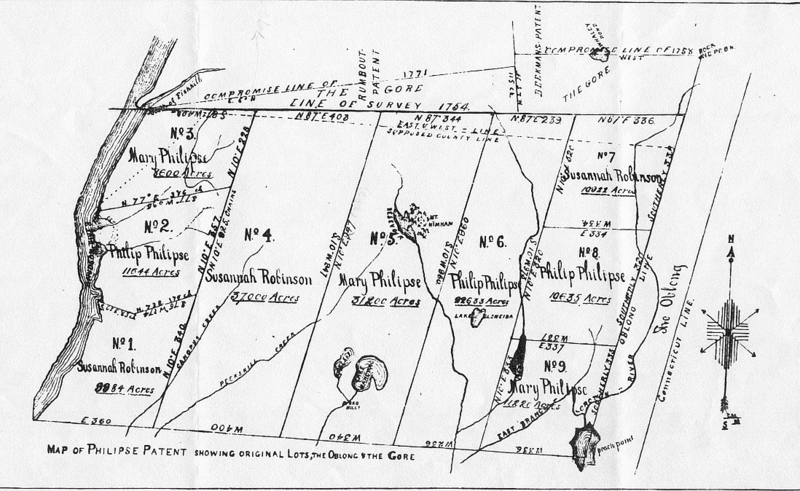

Daniel Babbit was born in 1744 at New Milford, Connecticut. When the Revolution began in 1775, he lived in Fredericksburgh, New York, then located in southeastern Dutchess County. He had a tenant farm from Beverly Robinson’s portion of the Philipse Patent consisting of eighty-seven acres. Babbit drew the ire of patriots early as October 1776, when a revolutionary committee ordered that he be “disarm’d apprehended and secured.” Three years later, Babbit decided to flee to British lines at Kingsbridge, just north of New York City, arriving on July 16, 1779. He then went to British-occupied Long Island where he took the oath of allegiance and worked as a blacksmith the remainder of the war.

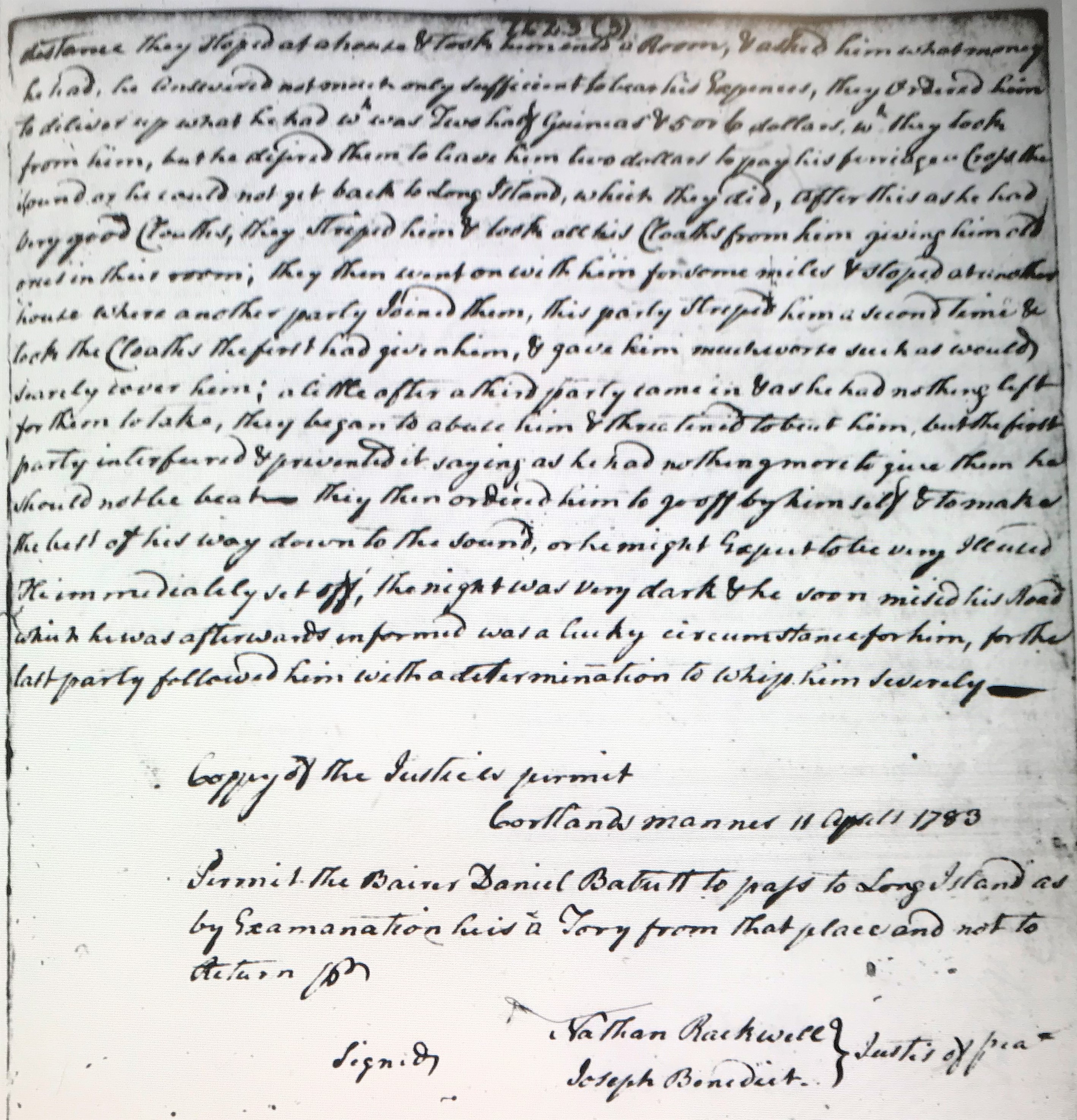

Like most Loyalists, he wanted to return to his home at the end of the conflict. In April 1783, he decided to risk the attempt, traveling northward towards Fredericksburgh. After getting within about fifteen miles of his home, Babbit was apprehended and brought before Joseph Benedict, a justice of the peace. Babbit told Benedict that because there “was now peace he thought he might go up to the place of his former residence to see his friends & to look after his property.” Benedict responded that because he was a “Tory,” he was not permitted to return home and he must immediately return to Long Island. Babbit was ordered to a separate room where Benedict’s son insulted Babbit and stole his hat.

Babbit was given a pass to return to Long Island. By this point, however, Babbit feared for his safety, commenting that the “people were much in raged against him” and asked that some men accompany him for protection against violent reprisal. Benedict sent his son and another unnamed man to protect Babbit. After traveling a short distance, the two men, rather than providing protection, took Babbit into a room. There they stole his money and clothes, giving him old clothes instead. After traveling some more miles, they stopped at another house where they were joined by a second party of men. These men stripped Babbit of the old clothes he had been given and gave him clothes that were “much worse such as would scarcly [sic] cover him.” A third party of men soon arrived who “began to abuse him & threatind [sic] to beat him” but were dissuaded by the first party. Babbit was then warned he ought to flee quickly for his own safety, which he did. The third party “followed him with a determination to whip him severely” but Babbit escaped and returned to Long Island.

Realizing he would face physical violence if he tried to return home again, Babbit decided to leave the United States and settle abroad. He moved to the Saint John River Valley in 1783, which became a part of the province of New Brunswick the following year. Babbit settled in Gagetown, Queens County, where he drew a town lot. He was also granted a farm on Washademoak Lake, but he later exchanged this property for land on Grand Lake, saying that the former property was too far from his house. Babbit became a prominent figure in early Gagetown, serving as a captain in the militia and working as both a blacksmith and a farmer. He was also a leading member of St. John’s Anglican Church, where he served as a warden for forty years and donated land where the first parish church was built in 1790.

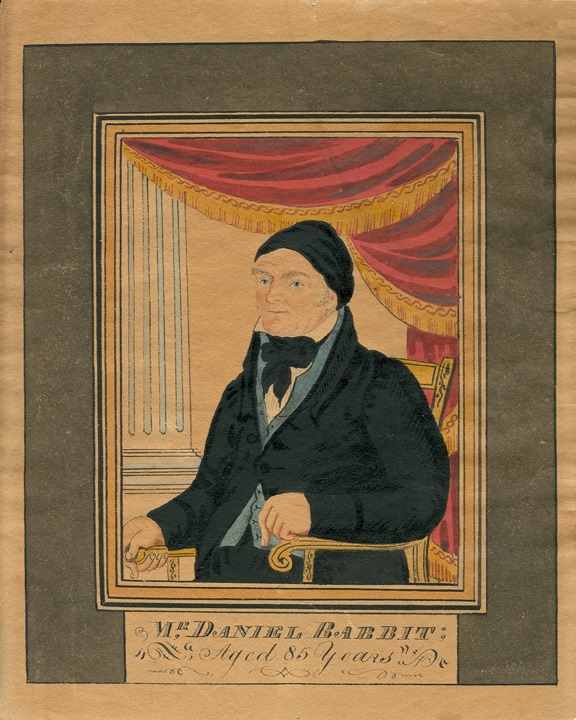

Babbit married twice. His first wife, Mary Close, died in 1795. He remarried to Rhoda Annis Cronk a few years later. Babbit had several children by each wife. In 1829, at the age of eighty-five and one year before his death, artist Thomas MacDonald painted a watercolor portrait of Babbit. The old Loyalist died the following year at age eighty-six or eighty-seven.

Babbit’s story shows how Loyalists who wanted to return home were sometimes deterred by the threat of violence. Instead, they were forced into exile abroad where they made a new life for themselves within the British Empire.

Primary Sources

Guy Carleton, British Headquarters Papers: 1747-1783.

New Brunswick, Surveyor General, New Brunswick Land Petitions: 1783-1834.

Victor Hugo Paltsits, ed. Minutes of the Committee for Detecting and Defeating Conspiracies in the State of New York: December 11, 1776-September 23, 1778. 2 vols. New York: New York Historical Society, 1925.

Secondary Sources

Browne, William Bradford. The Babbitt Family History: 1643-1900. Taunton, MA: C.A. Hack & Son, 1912.

Kieran O’Keefe is a Ph.D. candidate at The George Washington University. His dissertation examines Loyalists in the Hudson River Valley, exploring how conflict, upheaval, and forced migration to Canada shaped Loyalist communities during and after the war. Prior to attending George Washington, he received his M.A. from the University of Vermont and his B.A. from Mount Saint Mary College.

Add new comment