- Submitted on

- 0 comments

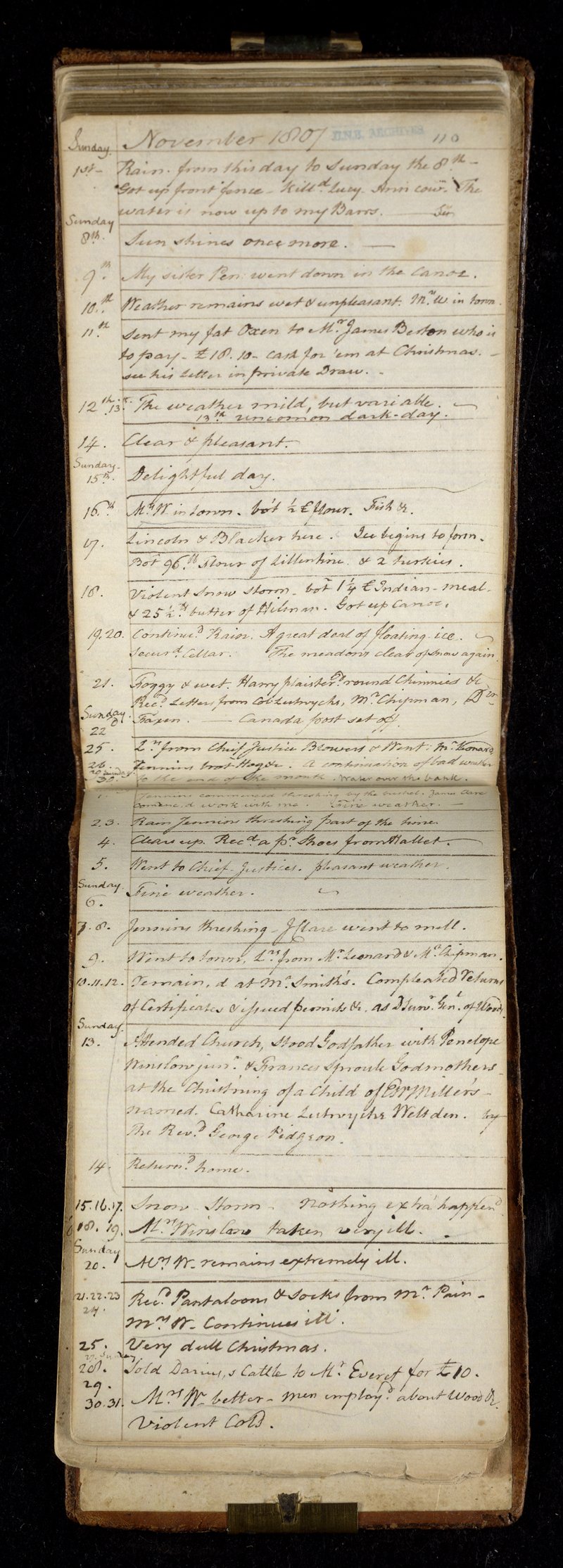

On December 25, 1807, New Brunswick Loyalist Edward Winslow, Jr. wrote in his diary: “Very dull Christmas.”

In the days before this entry, Winslow notes typical NB weather: “Snow storm--nothing extra happen. Mrs. Winslow taken very ill” and “Rec’d pantaloons and socks from Mr. Pain.” There is no mention of visiting with friends or family, feasting or going to church to hear a Christmas sermon, things we associate with Christmas today. In other Christmas entries in his diary, Winslow complains of gout, mentions killing hogs, carrying wheat to the mill, and other day-to-day business. At first blush, Christmas does not seem to be much of a holiday for Winslow.

Perhaps it was because Edward Winslow, Jr. was descended from the Puritans who founded Plymouth, Massachusetts, where he grew up in a mansion overlooking Plymouth Rock.

(Photo by Swampyank via en.wikipedia)

Back in 1765, when Winslow had just graduated from Harvard College, Christmas for the Puritans was certainly not the celebration it is today. Shops in Plymouth remained open for business on Christmas Day and it was often treated like any other workday. Diary entries from contemporaries in the late 1760s would often say things like: “Kept Christmas at home, and did a good day’s work.”

The following Christmas poem illustrates how Christmas was celebrated in 1765 in general by other residents of the American colonies, in this case from Virginia, which may have differed from Puritan Massachusetts:

Christmas is come, hang on the pot,

Let spits turn round and ovens be hot;

Beef, pork, and poultry now provide,

To feast thy neighbours at this tide;

Then wash all down with good wine and beer,

And so with Mirth conclude the Year.

Now Christmas comes, 'tis fit that we

Should feast and sing, and merry be;

Keep open house, let fiddlers play;

A fig for cold, fling care away.

And may they who there at repine,

On brown bread and on the small beer dine.

When New Year's Day is past and gone;

Christmas is with some people done;

But further some will it extend

And at Twelfth Day their Christmas end.

Some people stretch it further yet,

At Candlemas they finish it.

-Christmas is Come, Source: Joseph Royle, ed., The Virginia Almanack, 1765

Christmas celebrations back in England, and as imported by other immigrants to America, were frequently more secular than religious -- a time of feasting, drinking and boisterous behaviour, beginning for much of December and into January, which did not sit well with the Puritans.

Being a Tory, Winslow was forced to leave his ancestral, albeit Puritan home in 1776. He went with the British troops to Halifax, Nova Scotia, ultimately settling his family in the town of Fredericton in the newly formed Province of New Brunswick.

On a typical Christmas Day in the 1780s, after a long day in a court or council session in town, Winslow may have stopped by for a visit to the Officers’ Quarters as he made his way to his home out in Kingsclear, York County. The officers were probably celebrating Christmas by drinking rum, skating, or playing cards, or perhaps they would be holding a ball, dance, or assembly. “I am determined to figure at the Assemblies…” wrote Winslow to John Wentworth in 1784, so Winslow may have occasionally joined the officers in a Christmas assembly.

Perhaps he stopped at the market house open to buy a present for his wife, although perhaps he did what other Loyalists did and sent away to England for presents. Along the road home, Winslow may have dropped in on neighbours. As he wrote to Wentworth in 1784: “Till this winter, I had no idea of the jollity and sociability which a good neighborhood may enjoy in the coldest weather.”

Or Winslow may have stayed home to keep Christmas and to comfort his wife, as in 1784 his seven-year-old son Murray had been sent to school in England and would be spending the Christmas holidays there. Murray was supposed to spend Christmas with the Geyer family, but in a letter from Thomas Coffin to a Loyalist friend we find out it was not convenient for the Geyers to keep the “riotous” boy and he “remained a fortnight at school” over the Christmas holidays, which brings to mind lonely young Ebenezer Scrooge’s Christmas away from home and family.

In later years it appears Winslow kept Christmas with friends or family. In 1803 he writes in his diary that “all the remaining Winslows, Millers and Cloppers…kept Christmas at Kingsclear. No snow yet, good travel on the ice,” and in 1804 Lieutenant-Colonel James Chalmers wrote to Winslow saying: “I wish to acquaint you that you would gratify me exceedingly by dining with [me] on Christmas Day.”

“We only have time to say we have been all collected at Christmas from the Venerable Colonel and Mrs. Miller downwards,” writes Winslow to his son December 1811, “making with the young ones about 30, all in great spirits and good health, and all uniting in a flowing bumper to your long life and prosperity.”

And here’s a flowing Christmas bumper to all our readers!

Christine Lovelace is Academic Archivist at UNB Libraries, Archives & Special Collections.

Add new comment