- Submitted on

- 0 comments

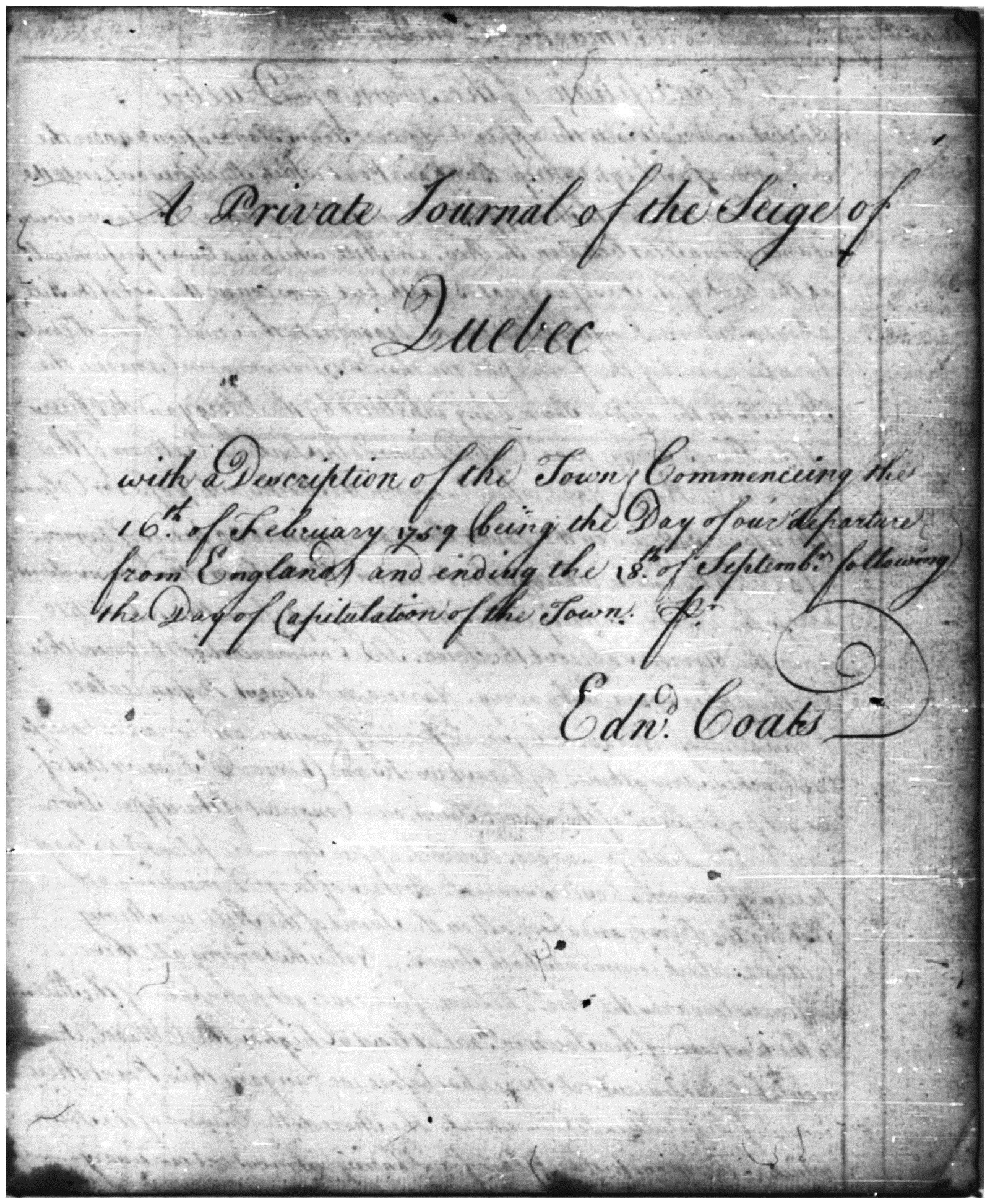

An eyewitness to the Siege of Quebec in 1759, Edward Coats accompanied the British on their journey up the St. Lawrence River to Quebec and eventually Montreal. Though his official position or title is not known, the fact that he was able to read and write and do so at a time of war, shows that he was not a common soldier, more likely a naval officer under the Command of Vice Admiral Saunders. Coats was not necessarily even involved in the conflict in any way, as a read through his journal gives an impression that much of what he wrote had been relayed to him by other men or commanders.

This journal is an excellent and interesting resource for those intrigued by this dynamic time in Canadian history. In his writing, Coats discusses the daily notable happenings on the ship, the troop and ship movements, British strategy, and various interactions the British troops had with the French and Indigenous peoples. The journal is much more descriptive than it is personal; we do not really get to see Coat’s personal musings or feelings at this time. Instead we must read between the lines, using the language and way in which he wrote about particular groups to understand his attitude. Given the high stakes at this time and the general French-English disdain for one another, it is unsurprising that this rhetoric would appear in his journal. It is also unsurprising that Coats would have a particular attitude towards Indigenous peoples, purely based on the time period and the fact that he was British.

Rather than go through the whole journal chronologically by entry date, I found it useful to “classify” my focus when looking through the journal. Being interested in the French – Indigenous – British dynamic at this point in Canadian history, I separated out these three groups and searched through the journal to find bits of information, recollection or description on each. At the beginning of Coats’ journal is also another unique piece of information: a full and detailed description of the town of Quebec. Not only was this very useful for the British plotting an attack, it is extremely useful today when we attempt to piece histories back together.

On Quebec City:

This unique piece of writing at the beginning of his journal starts as a sort of preface and allows the historian, and others who love history, excellent insight into what the town looked like and to visualize these surroundings in today’s modern world.

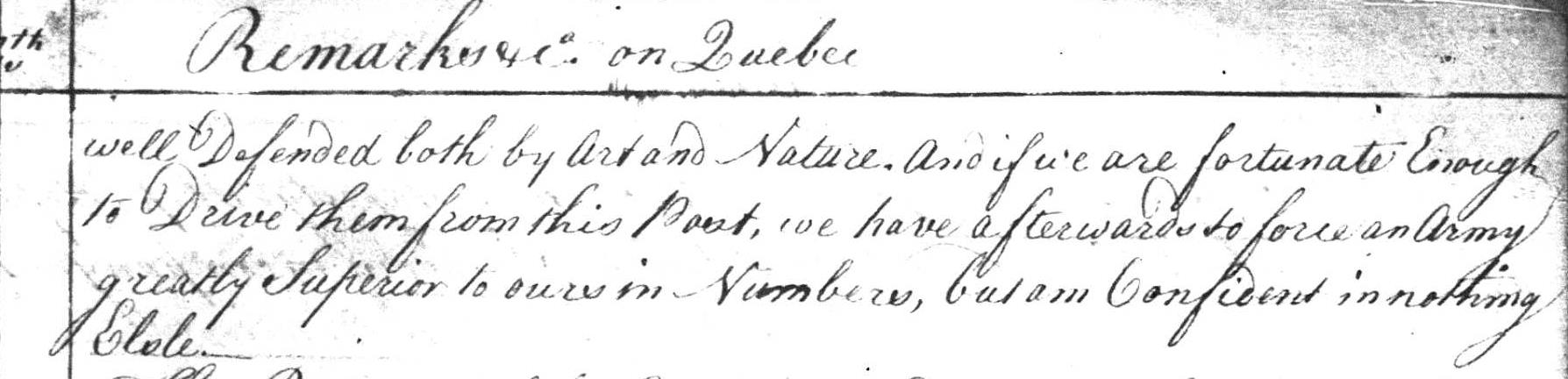

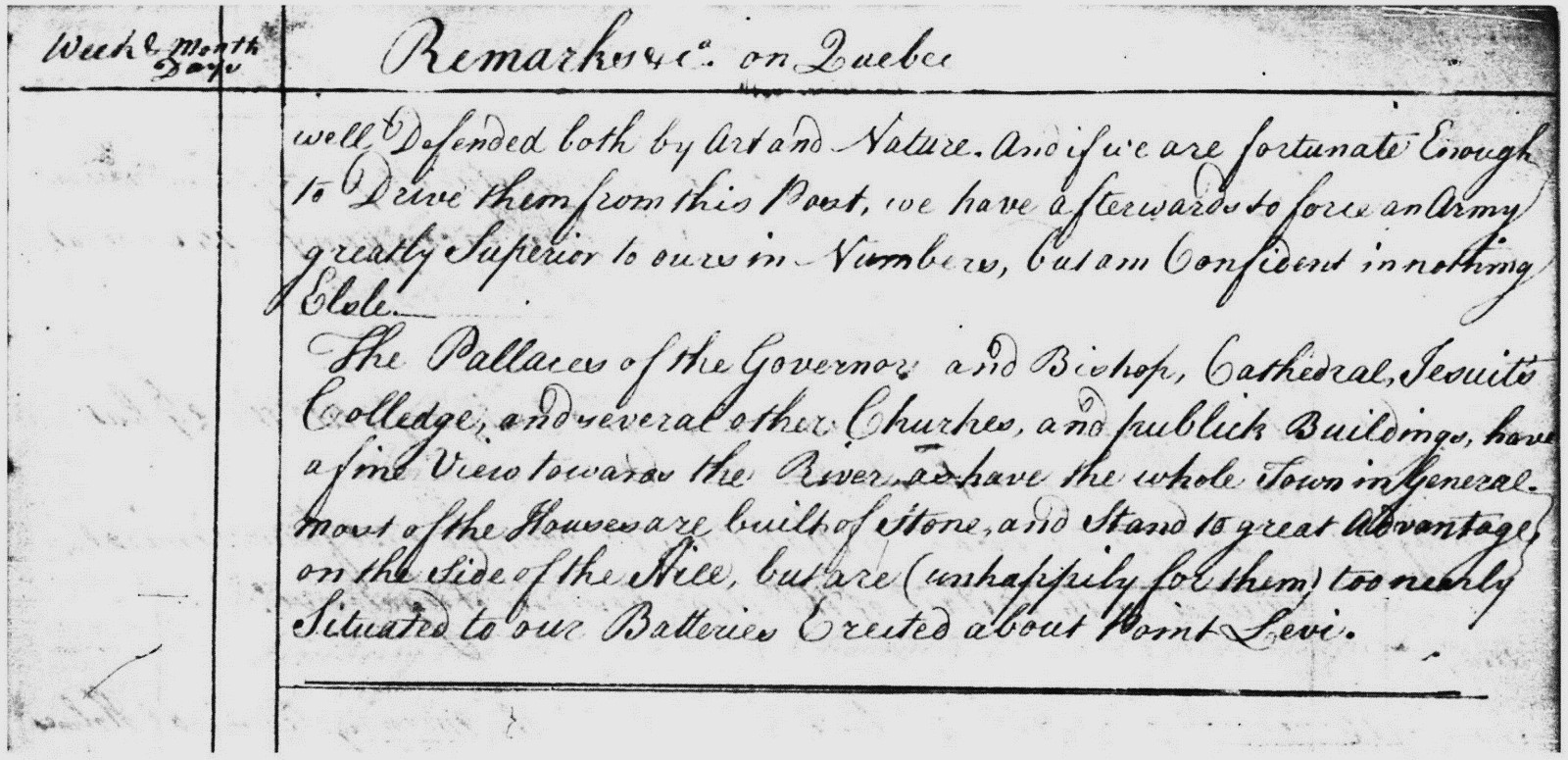

Coats remarked on the divisions in the city: the upper and lower town. The upper being inhabited by the clergy and the top military officers while the lower town is inhabited by the merchants and tradespeople. He made detailed notes of the town’s defenses: the locations and size of the cannons and various entry points and landing points to the city. He also took into consideration the various factors that would complicate each strategy. From his description, the taking of the city seemed insurmountable, but Coats remained optimistic:

At the end of his description of the town and surrounding area he commented on the civilian housing and the array of the public buildings within the town. His description is clearly more of a strategic record for the British, who were attempting to figure out at this early point how to overtake the town. He notes that “unhappily for them” many of the public buildings and residential areas are in striking distance of British batteries and as such would make good targets when overtaking the city.

On the British Force:

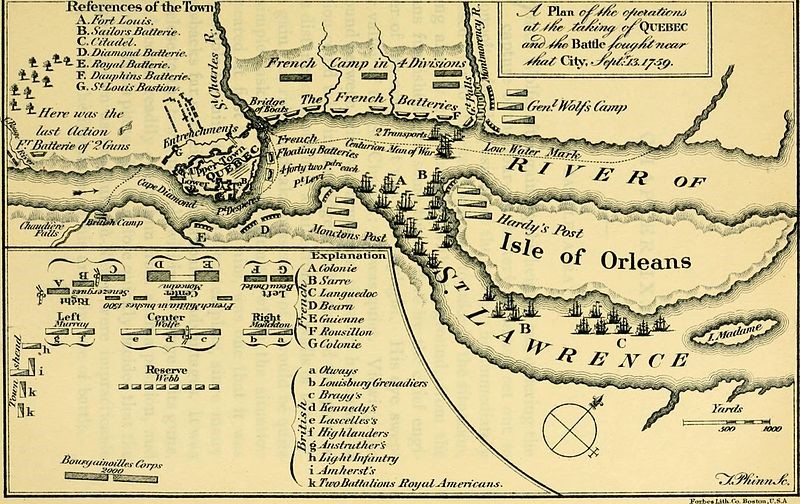

Coats’ journal starts with short entries on the progress the fleet has made past Louisbourg and down the St. Lawrence until they arrive at the French stronghold, Quebec City. Coats was aboard the Neptune. Listed at the back of the journal is his account of the various ship names and commanders, along with how many guns they had and the type of ship it was. The Neptune appears to have been the largest in this war fleet with 90 guns commanded by Broderick Hartwel. There are 34 additional ships, with the smallest of them having 20 guns. Along with these warships there are four sloops, three fire ships, an armoury ship and a cutter.

On Indigenous Peoples:

The first mention of Indigenous people is found on June 30, 1759, when Coats wrote about a “falling in” with the “Indians:”

“A body of Canadians and Indians incommoded our Troops at Pt. Levis, the Ground being Woody, but on their commanders being killed they dispers’d, with small Loss on our Side.”

Just this small excerpt gives us insight into the tense skirmishes that would be taking place due to the siege and in the lead up to the Battle of the Plains of Abraham. The passage also gives us an example of the variety of troops the French used as defense and the allegiances playing out. Their force was mainly made up of inexperienced Indigenous allies and French Canadians. While the Indigenous allies and French Canadians had been trained in French military practices and fire arms, they were not career-hardened troops who, because this was their living, were extremely disciplined. Only a small portion of defenses at Quebec City were made up of French regular troops. It is interesting to note, as earlier on in the journal Coats commented on the fact that the French were far superior in number. While the British had lesser numbers, all of their troops were trained regulars. This factor became decisive when the Battle of the Plains of Abraham was fought.

He also made reference to the practice of scalping, particularly by the Indigenous peoples, writing “[and] that inhumane Practice of Scalping either by Indians or others may be put a stop.” And in another passage he detailed the correspondence the British sent to the French in the city, firmly requesting that the barbaric practice of scalping on both sides be ended. The French did not heed this request, as Coats recalled in his journal.

On the French and their Defenses:

Much of Coats’ journal is concerned with describing troop movement and the progress that has been made by the British. But we also get a good description of the state of the French defenses at Quebec. On June 30, 1759, he wrote: “By Prisoners we learn that the Greatest part of the Canadian forces is drawn to Quebec for [?] Defense of it [?] are Encamped between the City and the Falls of Montmorency, about 18,000 strong, that their Regulars don’t exceed 3,000, the rest being Canadians and Indians train’d to Arms.”

Later, on July 4, he wrote about a correspondence received from the French. It was almost comical the way he wrote about the French response to the original British communication and it is easy to tell from his writing that the British were quite offended by it:

“They made no scruple of acquiring our Officer that they were well acquainted with our Force, and were greatly surprised we should attempt the Conquest of this Country with such a Handful of men – a great Instance of the Gasconading Disposition of the French.”

Clearly the British were displeased with the confidence that the French displayed in their correspondence. For those that were initially confused by the wording like I was, “gasconading” comes from the French word “gasconade” which means to extravagantly boast or have an air of bravado; arrogance.

Coats’ journal stops abruptly after the French surrender and British take over Quebec City in September of 1759. He included the Articles of Capitulation as one of the last entries. The journal provides extensive information regarding this short period of months during the siege and lead up to the Battle of the Plains of Abraham. There is much more that can be gleaned, studied, analyzed and written about from this document. It would also be intriguing to find more out about the figure behind this journal, Edward Coats. His journal provided much information regarding British troops and positions, the French and their Indigenous allies as well as on the city itself. Coats’ journal will continue to be a valuable resource in the study of Quebec and early Canadian History.

Oriana Visser is a student assistant in the Microforms Unit at the Harriet Irving Library. She is a third year Honours History Student who has a particular interest in pre-confederation (1867) Canadian history.

Add new comment