- Submitted on

- 2 comments

Blood-curdling shrieks filled Peter Huggeford’s operating room. Trails of blood pooled onto his oaken table, seeping into its crevices and staining the wood a dark burgundy colour. The sickly smell of gangrene and death filled the air. With a newly sharpened bone saw in hand, Dr. Huggeford went to work.

Born around 1725, Peter Huggeford grew up in England until his early twenties, when he crossed the Atlantic to emigrate to Westchester County, New York in 1745. Once in New York, Peter settled down and married a woman named Elizabeth (b. 1730, d. August 24, 1792). Before their deaths in the late 18th century, Peter and Elizabeth had 12 children, four of whom have been confirmed to have been named Martha, Jane (b. circa 1750), John (b. 1750, d. October 14, 1795), and Peter (b. 1766, d. September 27, 1795). Martha and Jane went on to marry Elias Hardy and Tertullus Dickinson respectively, two prominent New Brunswick loyalists, whilst John and Peter chose to follow in their father’s footsteps and became physicians in New York. In Westchester, Peter established his medical practice, choosing to specialize as a surgeon- a relatively grisly affair at the time.

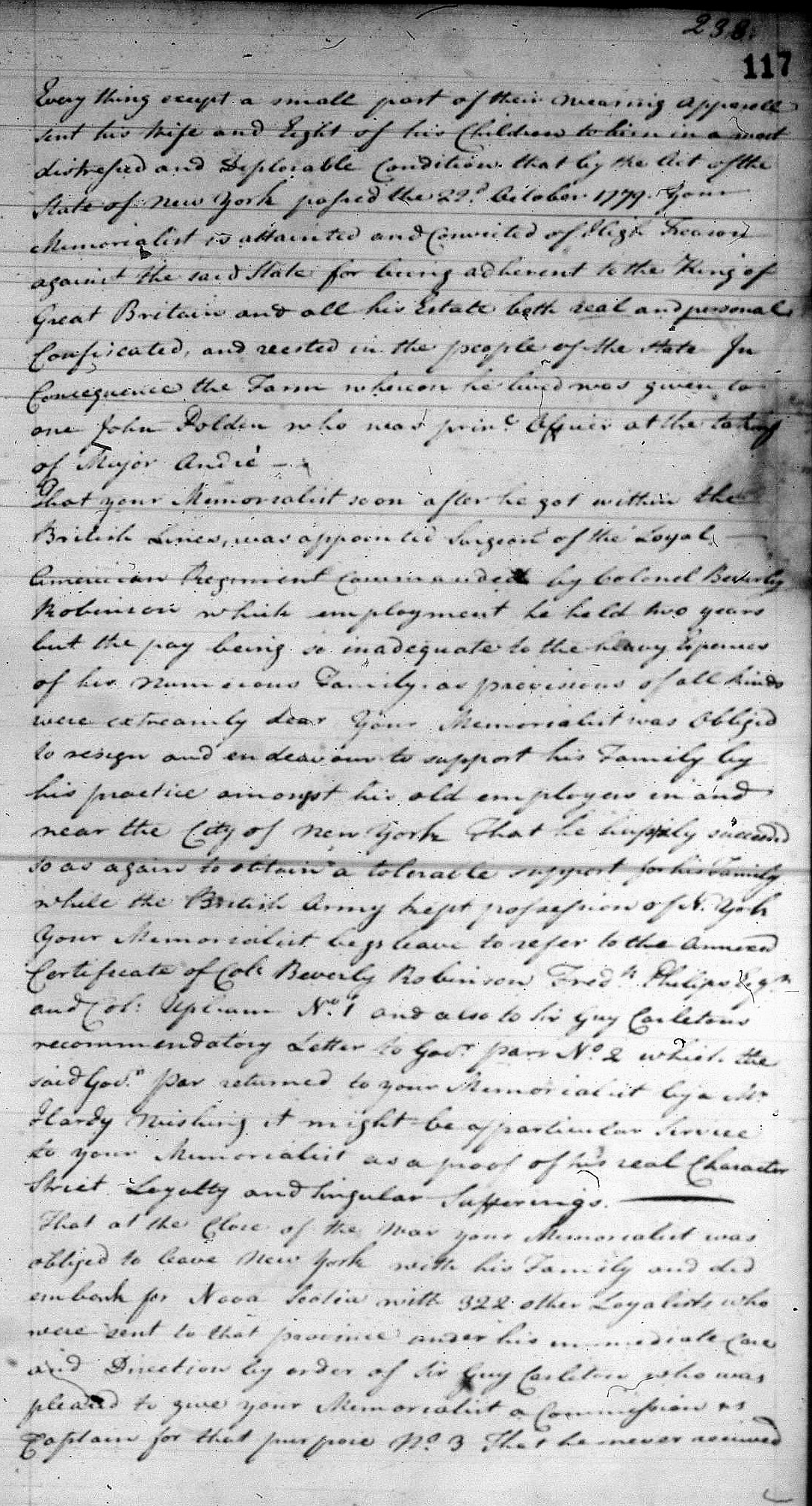

Peter was fiercely loyal to Britain throughout his entire life, a trait that would evidently be tested by the mid-1760s. Peter operated in Westchester up until the earliest rumblings of the Revolutionary War, choosing to stay loyal to the British rather than comply with the American revolutionaries. Peter stayed in New York until 1776, at which point he was “violently taken from his Family” and “carried to the White Plains,” where he would be confined in jail for the next two months. Upon his release from White Plains, Westchester, Peter was banished and sent to the early colony of Massachusetts Bay, where he was quickly detained and held captive for over six months. Afterwards, Peter was sent to Poughkeepsie, New York, where he was meant to stand trial for High Treason, a crime punishable by death. However, whether by brilliance or sheer luck, Peter managed to escape from where he was being held in Poughkeepsie and retreated back to the British Army, then stationed in New York. In 1779, his wife Elizabeth, along with eight of their children, removed to New York “in a most distressed and deplorable condition.”

(Great Britain Audit Office. Claims, American Loyalists: Series I (AO 12): 1780–1835. Vol. 21, reel 6, originals The National Archives, England)

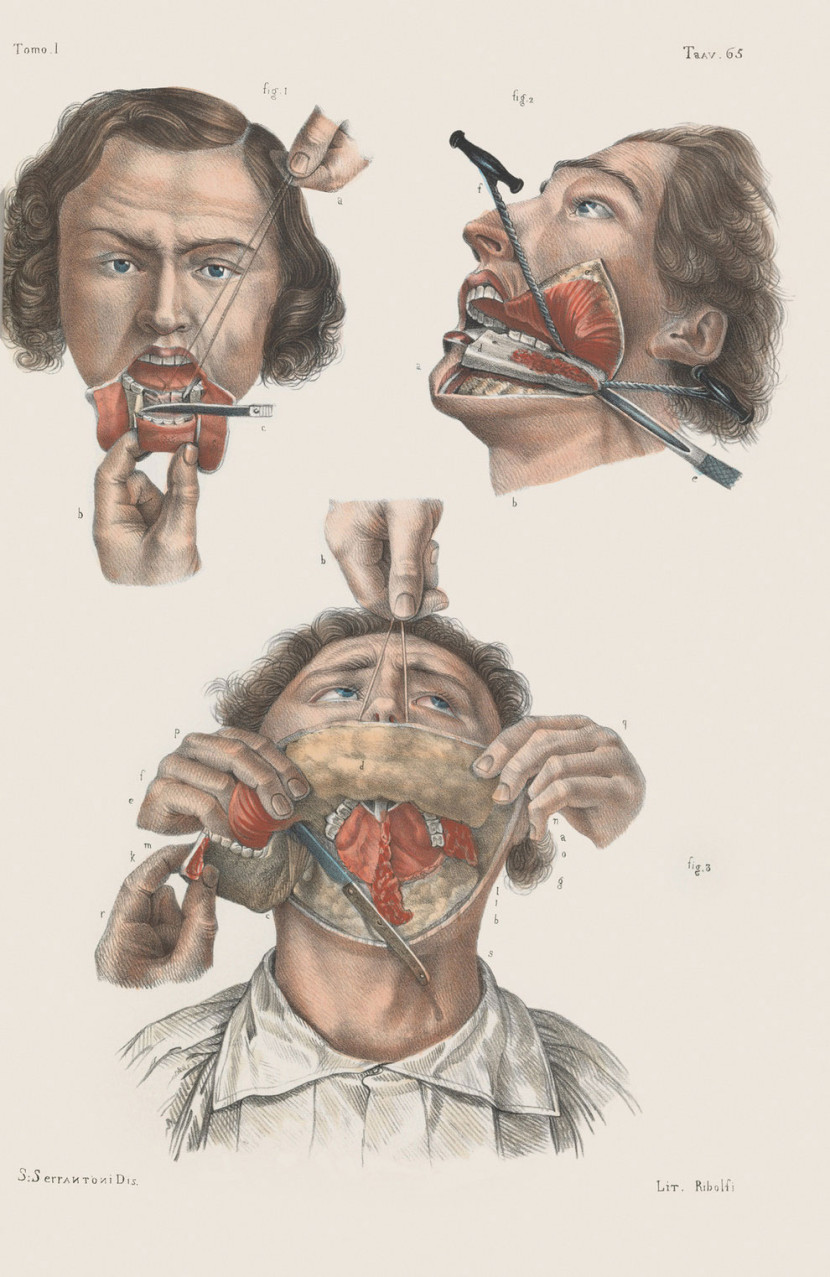

Once safely stationed in New York, Peter was appointed a surgeon for the Loyal American Regiment, commanded by Colonel Beverly Robinson. As a military surgeon, Dr. Huggeford tended to men on the brink of death, their mortified limbs blackened and reeking of infection. Stab and musket ball wounds riddled the bodies of British soldiers, while others suffered broken bones that jutted out of their diseased flesh. Yet, more often than not, the men who died on the battlefield had been the lucky ones. The others had to face the knives and saws of the military surgeons or otherwise face certain death.

(Barnett, Richard, and Roger Kneebone. Crucial Interventions: An Illustrated Treatise on the Principles & Practice of Nineteenth-century Surgery. London: Thames & Hudson, 2015 via The Wellcome Collection)

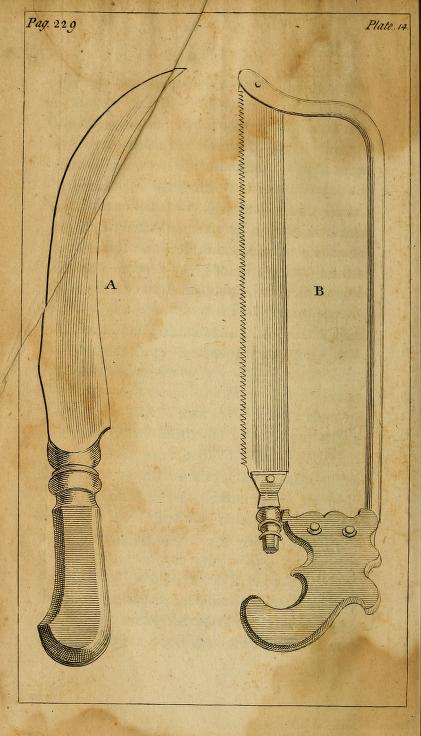

During the Revolutionary War era, surgery was a last resort. In 1750, anatomist John Hunter described the practice as “a humiliating spectacle of the futility of science,” while his brother William once said that a surgeon was “a savage armed with a knife.” A manual written in 1712 entitled “A Treatise of the Operations of Surgery” was once used to provide surgeons with gruesome details regarding a wide array of operations, including castration, amputation, cancer removal, and abdominal surgery. The treatise describes the practice of amputation in grisly detail:

“With a crooked Knife in his [the surgeon’s] right Hand, he makes an Incision to the Bone round the Member, and with the back of the Knife he divides the Periosteum, and at the same time cuts the Flesh and Membranes he finds between the two bones, lest he tears them with the Saw… You take the Saw and carry it obliquely on the Tibia, which serves as a support to saw the Fibula, which is by much the weakest.”

(Sharpe, Samuel. A Treatise on the Operations of Surgery, with a Description and Representation of the Instruments Used in Performing Them: To Which Is Prefix'd an Introduction on the Nature and Treatment of Wounds, Abscesses, and Ulcers. J. and R. Tonson, 1761. Public Domain via Internet Archive.)

Of course, all of these operations were performed without the help of any sort of anesthetic, the discovery of which only occurred in 1846. The surgeons themselves rarely fared much better than their patients. René Fülop-Miller, author of Triumph Over Pain once explained that “many surgeons became so haunted with the suffering, which was inseparable from their work, that they broke down mentally.” Dr. Peter Huggeford was no different, and he was left to suffer through the mental anguish of his profession for the better part of half a century. Those who remained relatively unscathed from their work must have been, at best, emotionally detached, and at worst, sadistic and cruel. During his stay in New York, Peter was largely underpayed and soon could not afford to support his wife and twelve children.

Eventually, Huggeford thought it wise to move on from New York. In 1783, at the close of the Revolutionary War, Peter was commissioned as a Captain for the 7th Company of Loyalists, destined for the Bay of Fundy aboard an unnamed vessel. With him was his wife and five of his children, as well as three servants. For a time, Huggeford and his family stayed in Parr Town (modern day Saint John, New Brunswick), before travelling to England to follow up on his claim for £3144 in lost property, £900 of which he was granted, along with a pension of £160 per year. Peter returned to the Maritimes in April of 1786, eventually settling in Digby, Nova Scotia. In Digby, Peter continued his practice as a surgeon and general physician, working primarily among the poor and downtrodden. According to Reverend Roger Viets, a Digby native, Peter’s work had been “unselfish and largely unrewarded” during his time in the province.

In 1790, Peter left Nova Scotia and returned to Westchester, New York, where he stayed with his wife Elizabeth for the remainder of their lives. In his old age, Peter chose to put down his scalpel and instead focus on pharmaceutical care. Elizabeth died on August 24th, 1792, and, as recorded in the newspaper, Peter died three years later in 1795: “On Sunday morning last, at Mamaroneck, after eight days illness, Peter Huggeford, Jun. Druggist of this city.”

Harrison Dressler is an Arts student entering his second year at UNB and worked as a summer student in the Microforms Unit.

Primary Sources

The Argus & Greenleaf’s New Daily Advertiser (New York), October 2, 1795 via America's Historical Newspapers.

Great Britain, Audit Office, Claims, American Loyalists: Series I (AO12): 1780-1835, (The University of New Brunswick, Harriet Irving Library, The Loyalist Collection).

Joseph de La Charrière, A treatise of the operations of surgery. Wherein are mechanically explain'd the causes of the diseases in which they are needful, grounded on the structure of the part; their signs and symptoms. Also many new remarks after each operation. To which is added, a treatise of wounds, and their proper and methodical dressings. Enlarg'd with an account of the bandages, and other apparatus necessary in each operation. Translated from the third edition of the French, enlarg'd, corrected and revis'd by the author, Joseph de la Charriere. London, MDCCXII. [1712] via Eighteenth Century Collections Online.

Samuel Sharpe, A Treatise on the Operations of Surgery, with a Description and Representation of the Instruments Used in Performing Them: To Which Is Prefix'd an Introduction on the Nature and Treatment of Wounds, Abscesses, and Ulcers. J. and R. Tonson, 1761 via Internet Archive.

Recommended Secondary Sources

Richard Barnett and Roger Kneebone, Crucial Interventions: An Illustrated Treatise on the Principles & Practice of Nineteenth-century Surgery (London: Thames & Hudson, 2015).

Allan Everett Marble, Surgeons, Smallpox, and the Poor: A History of Medicine and Social Conditions in Nova Scotia, 1749-1799 (Montréal: McGill-Queens University Press, 1993).

Watch for our next post: Medical Pioneers Part 2: Freaky Pharmaceuticals and Quack Cures

Comments Add comment

Peter Huggeford

Huggeford Images

Thank you for this great piece of information! This will be useful for an ongoing project on loyalist doctors.

Add new comment Comments