- Submitted on

- 9 comments

Ship names may be commemorative or symbolic, hold a social significance, indicate political change, or offer a perceived protection in the dangerous world of the sea. What thinking can be detected behind these naming choices? Often we do not have a record of who named the ships, but we might understand the motivations behind the name or the vision that the namer wanted to project. Ship names were important for the practical purposes of nautical law and business records. Ships, however, were also treated as something akin to a living entity; they were endowed with their own personality, and therefore, their names could be very significant.

(by Ambroise Louis Garneray, 1783–1857, Source: Maritime Museum, Public Domain via Wikimedia).

A particular grouping of ships that make an interesting study are privateers, ships licensed to seizure of valuable cargoes or whole ships belonging to enemy nations, who cruised the Atlantic waters of North America from the American Revolution to the War of 1812. The prizes of these privateer ships—the enemy ships they captured which were also known as “causes” in nautical courts of law—also provide an intriguing array of naming practices. For more background on privateering, see our previous post, “License for Piracy.”

The most commonly used names found among privateers on the British side who made declarations for letters of marque in the American Revolution included Active, Lively, Enterprize, Hazard, Defiance, Hope, Dolphin, Union, Fame, Betsey, Sally, Nancy, Eliza, William, Friendship, and Ann.

Ships often changed hands, and frequently captured ships turned were into privateers for the opposite side. Sometimes their names were changed, frequently because the original names had a political or historical connection to the adversary. An example of a name change of an American ship that became a privateer for the British colonies of New Brunswick and Nova Scotia during the War of 1812 was the Portsmouth Packet, which was changed to the Liverpool Packet when purchased by Enos Collins of Liverpool, Nova Scotia. Also, the American privateer Actress became the Dart, Juliana Smith was renamed Broke (likely for Captain Philip Broke), Commodore Barry (an officer in the Continental Navy during the American Revolution) became the Brunswicker, Governor Plumer (for William Plumer, Federalist Governor of New Hampshire and senator) became the Lunenburg (an important shipping town in Nova Scotia), and the American privateer Armistice became the well-known Nova Scotian privateer, Rover.

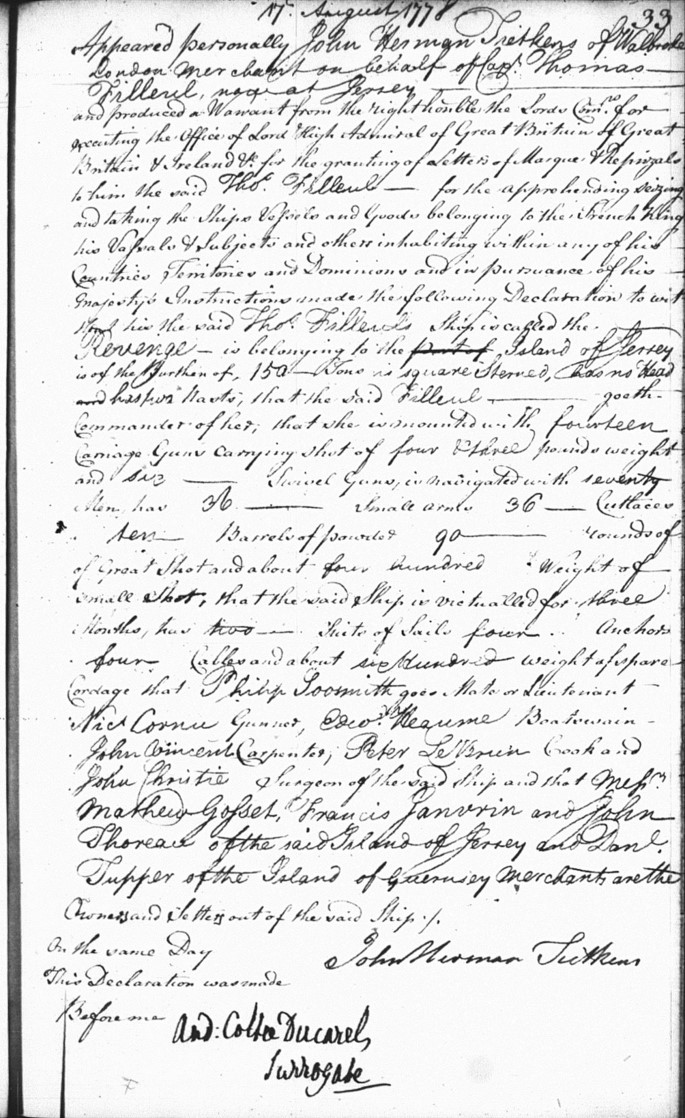

(Great Britain. High Court of Admiralty. Letters of Marque: Declarations Against America (HCA 26/60-7; ADM7/317-318) : 1777 - 1783. The Loyalist Collection, original held by The National Archives)

Names that did not change when captured ships came under new ownership in the British colonial Maritimes included the Gleaner, Rolla, Snapdragon, and Saucy Jack. Another interesting example was the Bunker Hill, named for a Revolutionary battle of significance to both the British and Americans; the American publication, Niles’ Weekly Register noted the capture of the American ship thusly, “Like the memorable place after which this vessel was named, she has cost the enemy more than the possession is worth.” For further information on privateering in the War of 1812, please see Faye Kert’s extensive work.

From 1784 to 1813, letters of marque were granted by the British against France and Spain, as well as America. Sometimes names of captured ships were translated, and this particularly occurred when French for Spanish ships were captured, although sometimes the original names were retained. Some examples of ships captured with names of French origin in the Atlantic included: La Prevoyante (foresighted), La Raison (the reason), Le Levriere (greyhound), de la Furieuse (the furious), Le Fantome (ghost), La Reine des Anges (the Queen of Angels), and Guerrier (warrior). Examples of Spanish derivation included: La Feliz (happy), La Liebre (hare), Alianza (alliance), and San Joaquim (St. Joachim). At times, an “alias” was included in the list of causes (e.g. Three Friends alias HMS Pictou and Santiago alias Caravan). The names chosen among Spanish and French ships appear to have been similar in type to American and British ships.

Ship names can easily be categorized into groups, the first of these being people’s names. Female names, coinciding with the tradition of ships being seen as female entities, were popular. Nick names and common names (e.g. Hetty, Fanny, Nancy, Lucy, Jane) were frequently chosen, but also more uncommon names (Felecity, Roxana, Alvira, Eunice) or a name with an adjective (Charming Sally, Little Charlotte) were used as well. Of course, male names were used also used, with nicknames also dominating, and adjective combinations appearing such as Loyal Sam. The motivation behind the names of ships given common first names is hard to uncover, perhaps with family members of ship owners or builders often being the inspiration.

Other ship names came from last names, but some referred to a specific person, using both their first or last name, often to honour an original owner or builder of the ship. A group of people could be unnamed (such as Two Sisters, Three Friends, Three Williams, Four Sons, Three Brothers) or named (Joseph & Elizabeth, Mary & Ann), indicative of partnerships or familial relationships. Occupations and nationalities were also employed in ship naming such as Indian Trader, Arab, West Indian, New Zealander, Micmack, Acadian, Hussar, Post Boy, Ploughboy, Mentor, Bachelor, Freemason, Old Carpenter, and Mariner, all found in causes (captured ships) brought to Nova Scotia from the American Revolution to 1813.

Contemporary “celebrities” offered a great pool of name choices inspired by military figures, political figures, and royalty. Privateers named after British administration and royalty operating circa 1812 out of Nova Scotia included: Charles Mary Wentworth (named for son of then governor of Nova Scotia, Sir John Wentworth), Sir John Sherbrooke (originally the American privateer brig Thorn from Marblehead, Massachusetts, renamed after the former colonial administrator Sir John Coape Sherbrooke), and Duke of Kent (King George III's fourth son, Prince Edward Augustus).

On the other side of the American-British divide, prize ships brought into Halifax, Nova Scotia named for persons of renown from 1784 to 1813 included heroes of the American Revolution and early American politics: George Washington (the ship was captured in 1794), General Green (named for Major General Nathanael Greene of the Revolution) as well as Lady Green, Jefferson, Adams, Hamilton, Franklin, Moses Myers (a Jewish-American merchant Norfolk, Virginia), General Putnam (referring to Israel Putnam, 1718-1790, American officer nicknamed “Old Put” who was famous during American Revolution), and Governor Shelby (for Isaac Shelby, 1750-1826, the first governor of Kentucky who fought in the Revolution and War of 1812). Interestingly, European nobility was also accounted for among the captured American ships, such as Frederik Augustus (likely referring to the Kings of Saxony from 1806-1827) and Prince of Austria (probably Crown Prince Ferdinand, first Heir to the Austrian Empire). Also from history and literature respectively, Montazuma (Moctezuma I and II were Aztec emperors in the fifteenth and sixteenth centuries) and John Milton (English poet and civil servant of the seventeenth century) were used as ship names.

Make sure to stay tuned for the second part of this post: Revolutionary Names: Privateer and Prize Ships, 1777-1814, Part 2

Please see The Loyalist Collection’s Piracy and Privateering Subject Guide for more sources and information.

Leah Grandy holds a PhD in History and works as a Microforms Assistant at the Harriet Irving Library.

Comments Add comment

Source for "Broke'

Thank you!

Thank you for this further information and your interest; it is much appreciated and edits have been made.

American prize master

Prize Master

Thank you for your interest. You can find the second installment of the post here: https://loyalist.lib.unb.ca/atlantic-loyalist-connections/revolutionary…; Any research queries may be sent to mic@unb.ca.

Captain Perkins Allen

Captain Perkins Allen

Captain Perkins Allen

Curvo, Maine

Curvo, Maine

Add new comment Comments