- Submitted on

- 0 comments

“A letter of marque came from the king to the scummiest vessel I’d ever seen,” is a line which rings familiar to many ears thanks to Stan Roger’s popular song, Barrett’s Privateers (1976). Letters of marque were issued by nations during times of war allowing privateering activity, which consisted of the seizure of valuable cargoes or whole ships belonging to enemy nations, an approach to war often termed guerre de course. The Loyalist Collection contains a wealth of material linking Loyalists to the larger Atlantic world, and one of the most compelling group of documents which demonstrates these connections are documents surrounding privateering activity.

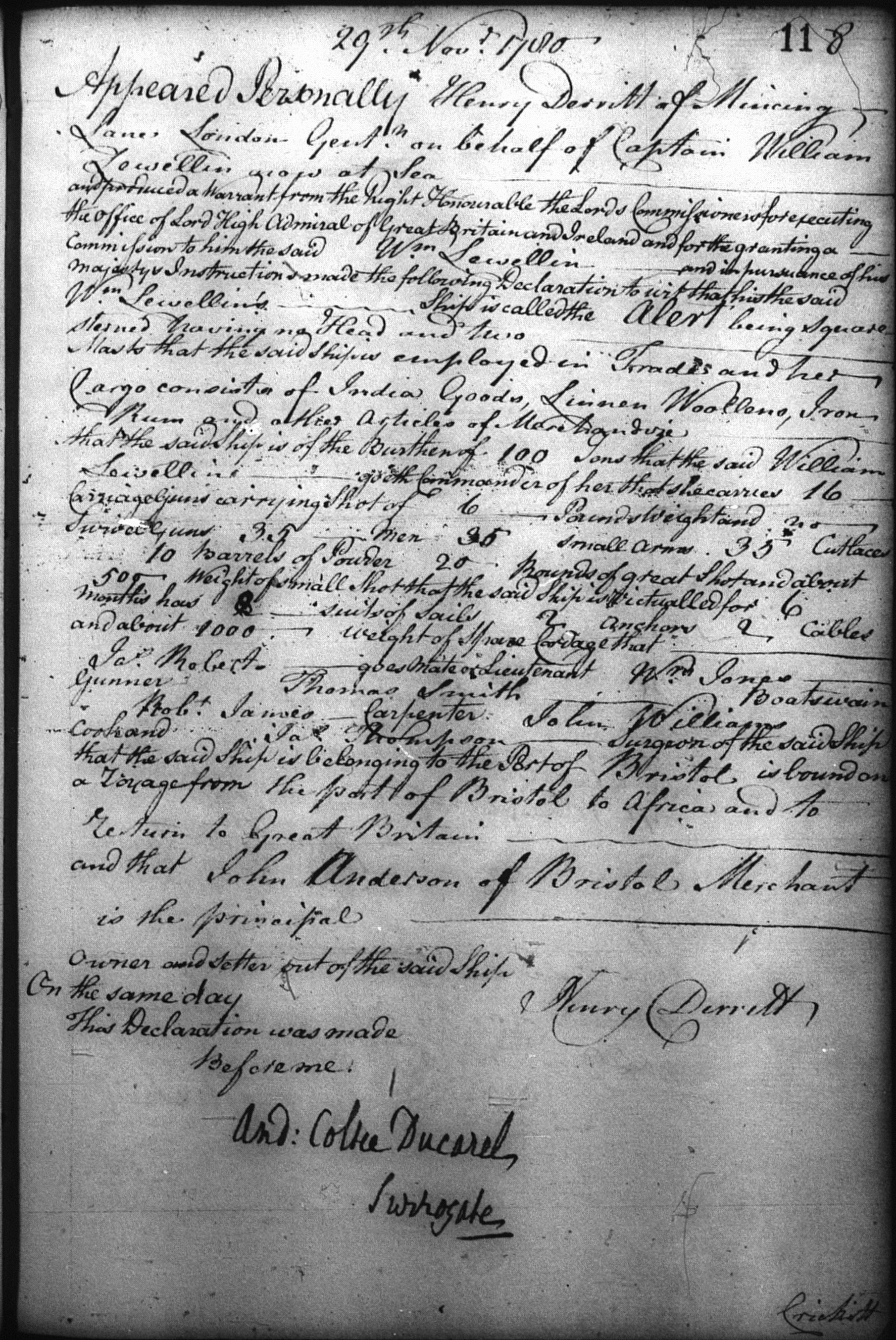

Declarations, which ship owners or their representatives submitted to receive letters of marque, provide a trove of information on vessels, their crews, and sea commerce. One of the interesting items which may be gleaned from a perusal of declarations are the names of privateering ships, some which express power and speed—Speedwell, Heart of Oak, Fearnought; some displaying outright aggression—Terror, Kidnapper, Vengeance; and some of a more gentle nature—Olive Branch, Good Intent, Resolution. Vessel types for privateers are also easily gathered from the documents, the most common types being schooners, sloops, brigs, ships, and brigantines, and less frequently pinks, frigates, shallops, snows, barques, and luggers. The real insights into the experience of privateering, however, arise once documents from various collections are combined.

(Courtesy of the Queens County Museum)

Using the Nova Scotia Court of Vice-Admiralty records as a starting point, the name of the schooner Retaliation, a privateer out of Liverpool, Nova Scotia, appears; it was formerly the American privateer known as the Revenge, a particularly interesting renaming choice! Originally from Salem, Massachusetts, the Revenge/ Retaliation while under the command of John Sinclair Jr. was captured on December 14, 1812 by the Paz. The Retaliation was very successful in its cruises out of Nova Scotia, receiving three letters of marque under three commanders in 1813, and seizing nineteen captured ships or “prizes”.

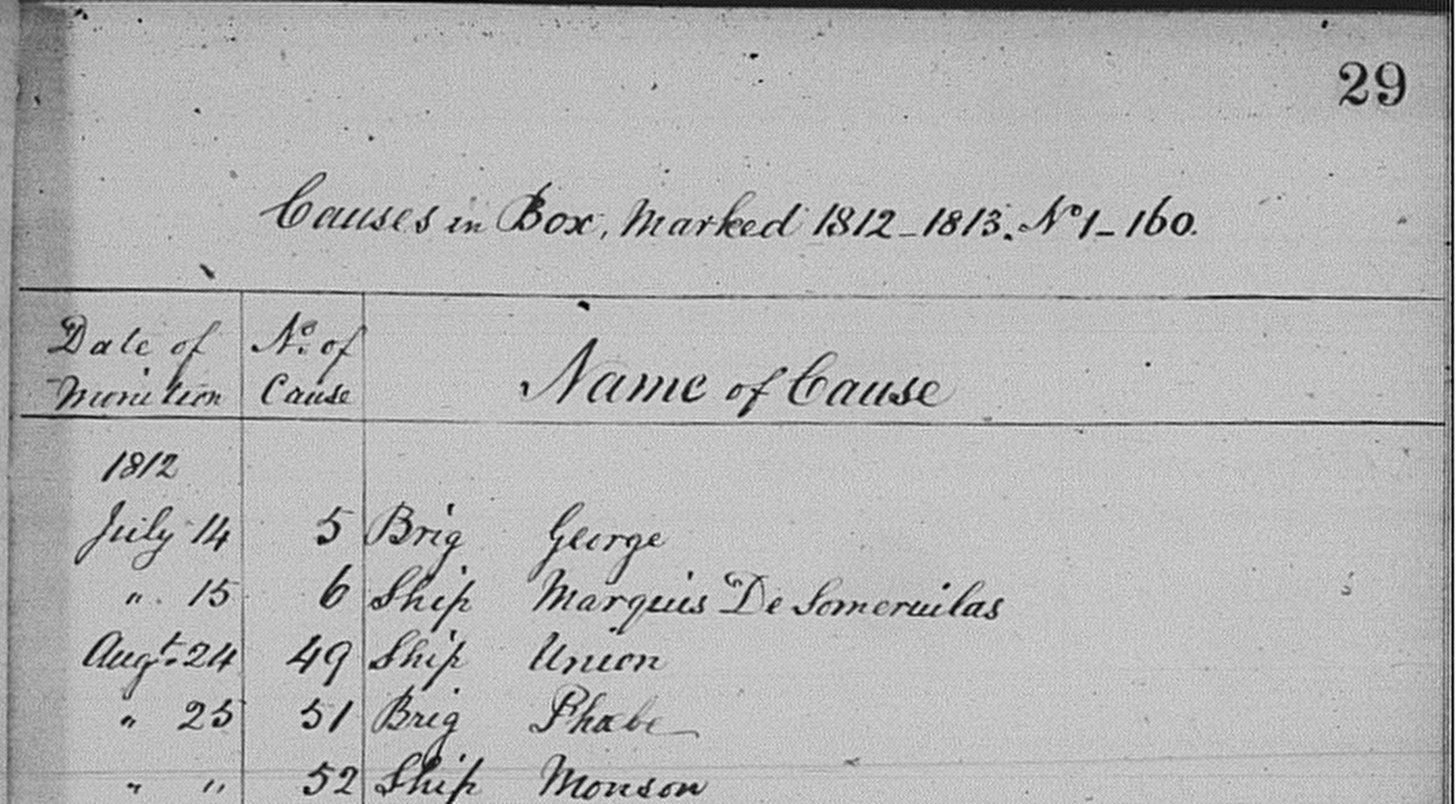

The intriguing case of the Salem trading ship, the Marquis de Someruelas emerged from two sets of records found in The Loyalist Collection. The Marquis de Someruelas (named for a governor of Cuba) while returning from Civitavecchia, Italy with cargo including art for the Academy of Arts in Philadelphia, was captured at the very outbreak of the War of 1812 on July 19, 1812 by the HMS Atalante, commanded by Frederick Heikey or Hickey. The owners of the Marquis de Someruelas sent a letter, preserved in the American Department of State's War of 1812 Papers, on August 31st to James Monroe, American Secretary of State at the time, pleading for intervention and describing the events that had transpired, saying at the time of the capture, neither vessel had known about the outbreak of war. The captain of the Atalante suspected the Marquis de Someruelas of carrying goods from Leghorn in Tuscany, an enemy port, and brought her in to Halifax for examination, where a decision regarding the ship was suspended. The Marquis de Someruelas (variously spelled) is indeed listed among the records of the Nova Scotia Court of Vice-Admiralty as a prize or cause:

The ship had already been attacked by pirates in Sumatra in 1806, but escaped to return to Salem, while its captor, the Atalante, suffered ill luck as well when it was wrecked off Halifax on November 10, 1813.

Through the broad span of documents available within The Loyalist Collection, an overall picture of privateering and prize taking in the Atlantic world from the midst of the American Revolution to beyond the War of 1812, and from Bristol, England to Halifax, Nova Scotia to Savannah, Georgia may be glimpsed. Although administrative documents, the examination of privateering records hint at the possibility of the enterprises, conflicts, and exploits which they made possible.

Leah Grandy holds a PhD in History and works as a Microforms Assistant at the Harriet Irving Library.

For more material on privateering, see the guide to The Loyalist Collection: Piracy and Privateering.

Add new comment