- Submitted on

- 0 comments

18th century New Brunswick and Nova Scotia was home to a slew of great and respected doctors and physicians, including but not limited to Drs. William Paine, Samuel Moore, John Gamble, Charles Earle, Thomas Emerson, Azor Betts, David Brown, Nathan and William Howe Smith, and Peter Huggeford, an English surgeon and subject of the last blog entry. However, respected doctors like Huggeford and Paine were not alone in the Maritimes. In fact, they had to consistently fight for a portion of the market share against hordes of small-time peddlers and quacks, selling potions, elixirs, and powders in the hopes of making a quick buck. This was the age of faux doctors and “patent medicine”, proprietary cures marketed to the masses with colourful imagery and striking slogans, all available without prescriptions or a referral.

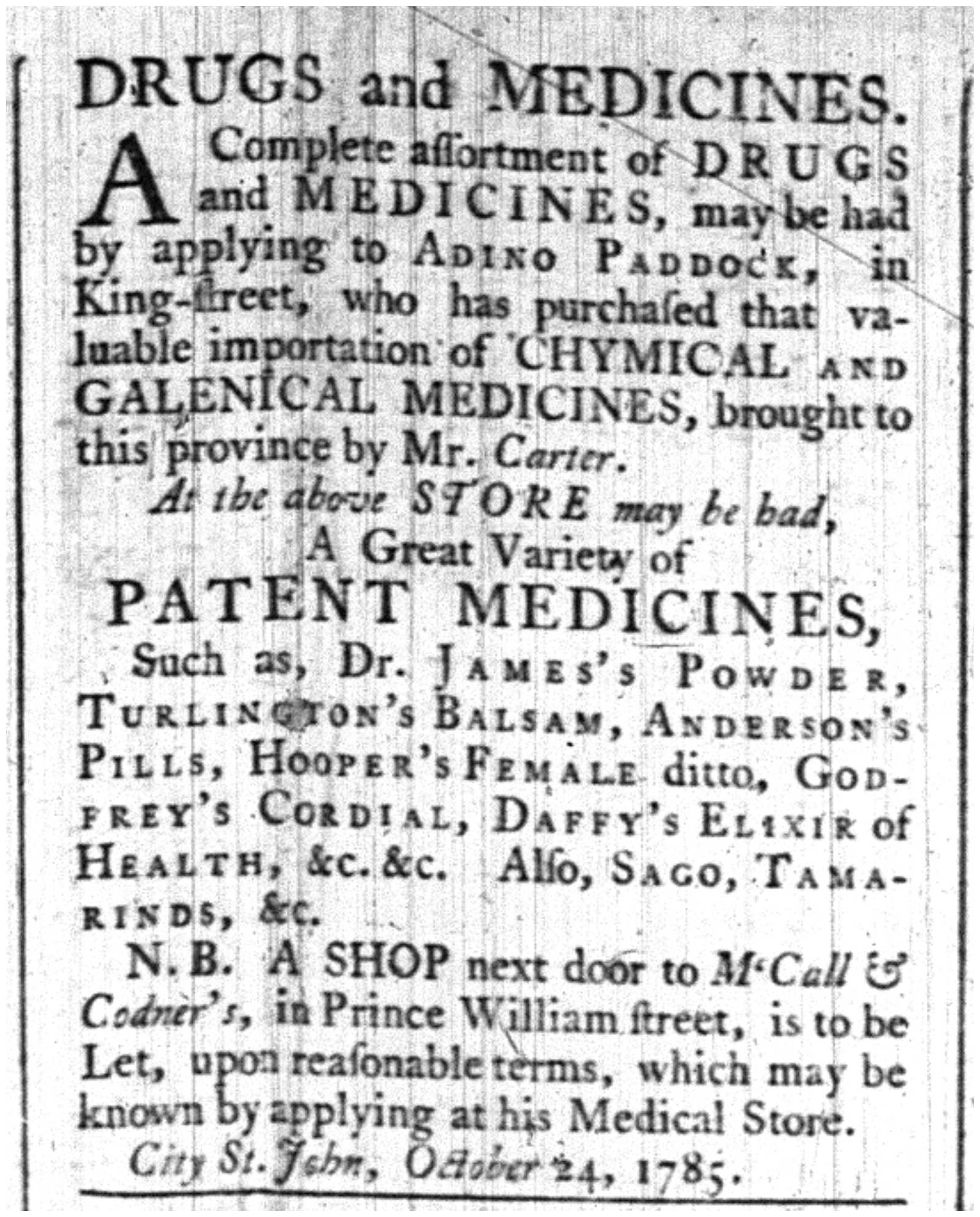

The Royal Gazette and New Brunswick Advertiser (Saint John), November 1, 1785. (UNB Libraries, Microform Newspaper Collection)

New Brunswick’s early newspapers were littered with advertisements for these same pills, potions, and powders. One notice posted in the Royal Gazette and New Brunswick Advertiser in 1785 announced the arrival of a number of new medicines at Adino Paddock’s medical store, including Dr. James’s Powder, Turlington’s Balsam, Anderson’s Pills, Godfrey’s Cordial, Daffy’s Elixir of Health, and Hooper’s Female Pills.

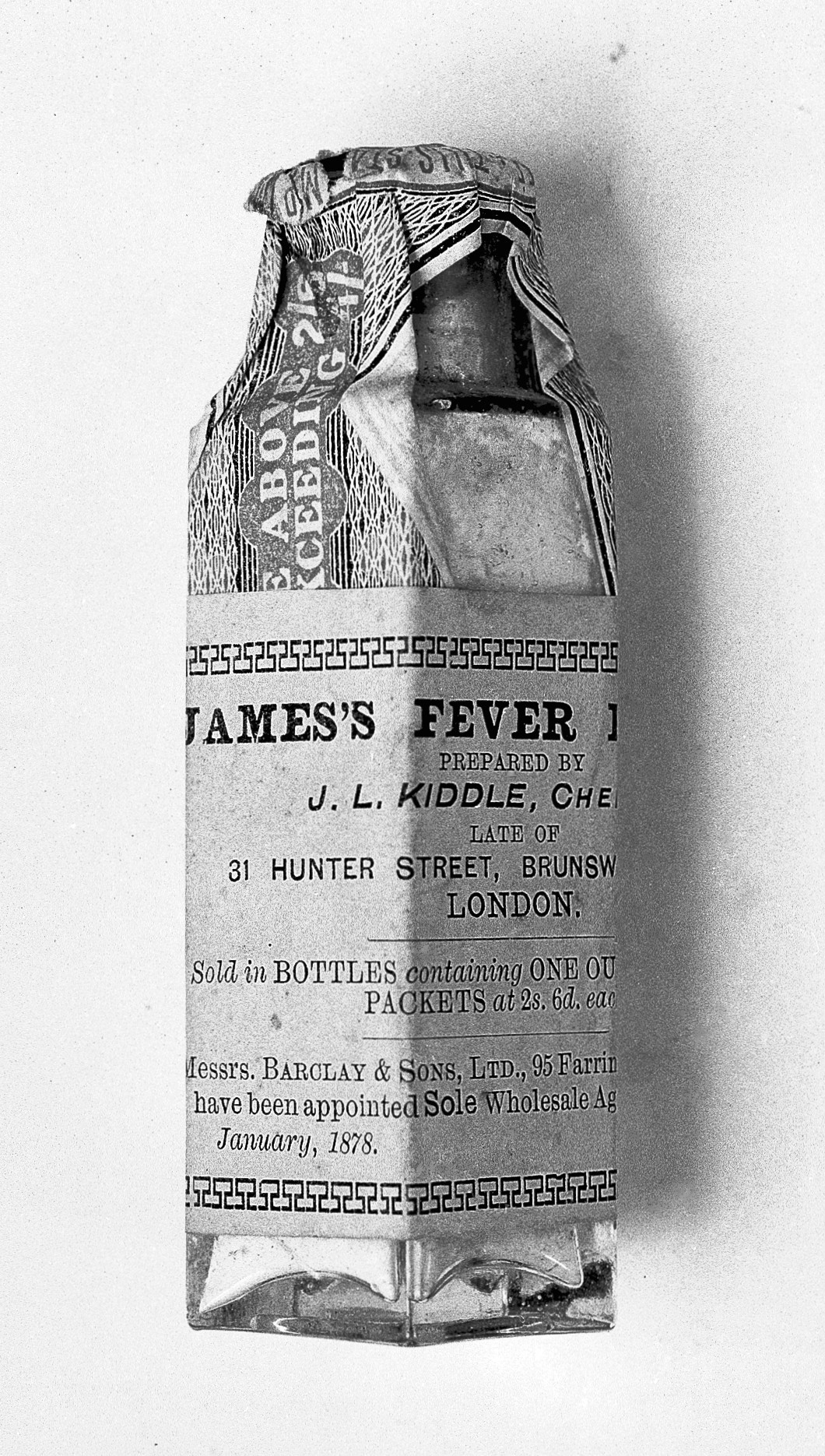

(Courtesy of Wellcome Collection)

The first of this list, Dr. James’s Powder, refers to Dr. James Fever Powder, a popular patent medicine created by English physician Dr. Robert James. His “Fever Powder” claimed to be able to cure a wide array of ailments, including gout, scurvy, general fevers, and even distemper, a viral disease found in dogs and cattle. Just like many other patent medicines, the powder’s efficacy was often questioned, but its “long tradition of usage” meant it remained a household name up until the 20th century. In 1791, chemist George Pearson was able to determine that the concoction was made up of a blend of antimony and calcium phosphate. A toxic substance, antimony can cause respiratory irritation, pneumoconiosis, spotting of the skin, and gastrointestinal problems.

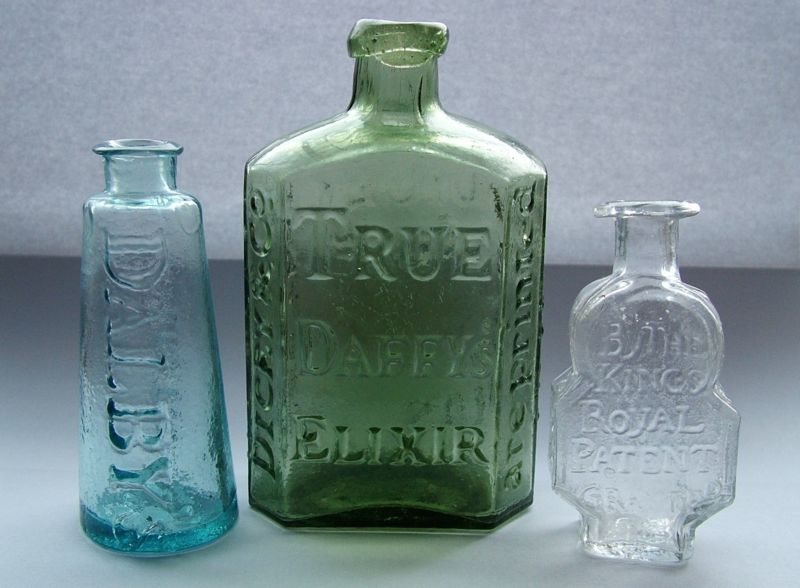

(Courtesy of Wikimedia under public domain)

Another massively popular medicine at the time was Daffy’s Elixir or Elixir Salutis, which literally means elixir of health. The quack medicine was invented at some point during the mid-17th century by Reverend Thomas Daffy, and marketed as being “the choise drink of health or health-bringing drink … a secret far beyond any Medicament yet known.” The formula that made Daffy’s Elixir was published in 1836 by Pharmacopoeia Londiensis as follows:

“Take of senna three ounces and a half,

Caraway, bruised, three drachms and a half,

Cardamom, bruised, a drachm,

Raisins five ounces,

Proof spirit two pints;

Macerate for 14 days and strain.”

While Daffy’s Elixir may not have been as inherently dangerous as Dr. James Powder, it’s doubtful that it did anything more than make its users a little lightheaded and tipsy.

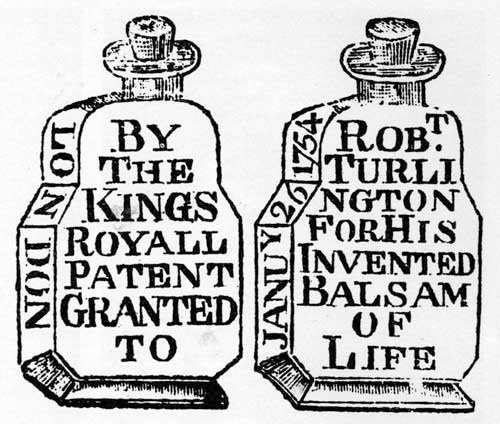

(Courtesy of Wikimedia under Public Domain)

Other patent medicines proved to be even more heinous. When it was produced, Turlington’s Balsam of Life contained a slurry of essential oils and ammonia, a toxic chemical that can cause permanent burns and even death if inhaled or ingested in high concentrations. The product was marketed as a miracle cure, capable of curing “everything from cough to stomach complaints to kidney stones to paralysis.”

Somehow even worse was Godfrey’s Cordial (also marketed as Mother’s Friend), a concoction that claimed to be capable of curing a myriad of ailments in infants. However, Godfrey’s most definitely killed far more children than it cured: “Despite their innocuous names, they were sinister preparations because of their opium content; Godfrey's Cordial contained one grain of opium in each two ounces.”

“Many infants died from opium poisoning in the early 1800's, usually as a result of its surreptitious use by nurses to keep infants under their care in a deep state of sleep and thus of no bother to the nurse responsible for them.” (Pediatrics 45, no. 6.)

(Courtesy of Duke University Libraries under Public Domain)

Often times, these medicines reflected the fears, worries, and values of the people of their era. For example, Hooper’s Female Pills were said to be able to cure “giddiness… Sinking of the Spirits, a dejected Countenance, and Dislike to Exercise or Conversation” among other things. In a sense, society’s response to a woman who “didn’t smile enough” was to prescribe concoctions of ferrous sulphate, ferrous carbonate and “therapeutically significant amounts of iron,” which Hooper’s Female Pills always had in excess.

All of these patent medicines and more were available at Adino Paddock’s medical store on King Street, Saint John. During his lifetime, Paddock had been a respected doctor in NB, making it even more challenging for consumers to distinguish the actual medicines from the often times deadly quack remedies.

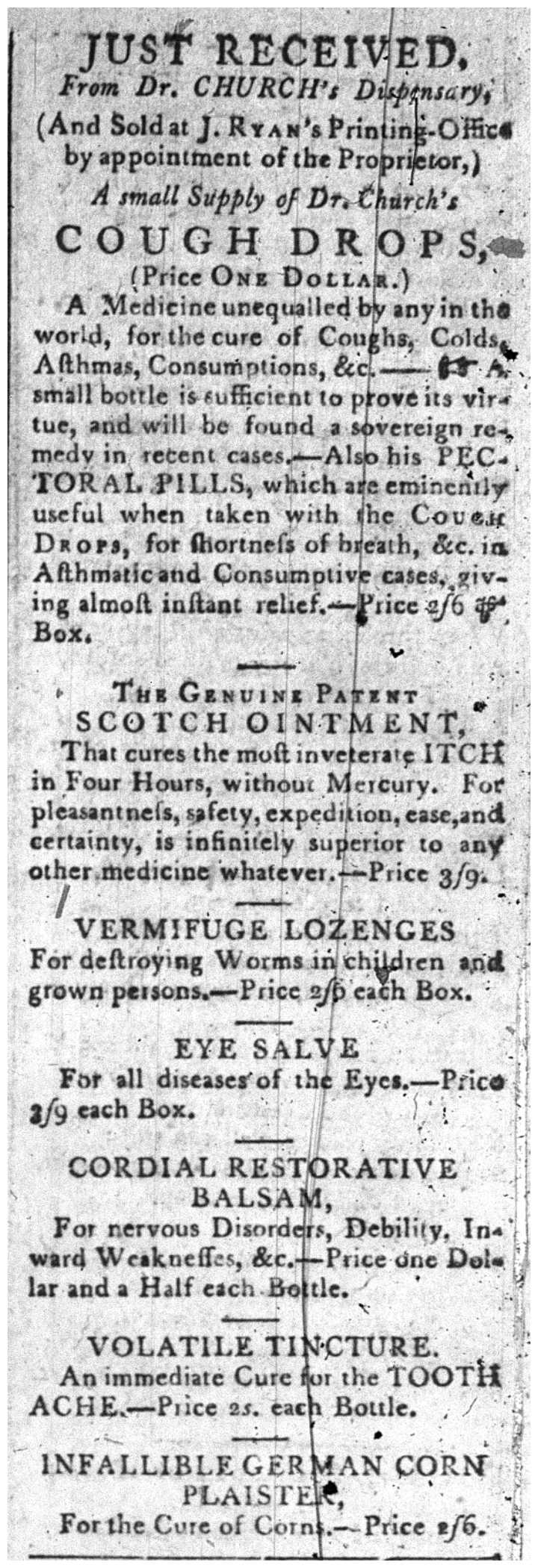

The Royal Gazette and New Brunswick Advertiser (Saint John), April 15, 1800. (UNB Libraries, Microform Newspaper Collection)

Other postings in the Royal Gazette advertised Scotch Ointment, Pectoral Pills, Vermifuge Lozenges, Jesuit’s Drops, and Infallible German Corn Plaisters. Another article, originally posted in Liverpool, England, suggested the use of yeast to cure “putrid fevers”, known today as diphtheria: “A table spoonful given in a little beer, ale or water, every hour or two, effects to speedy a cure.”

While some of these “medicines” were in fact harmless enough, many and more contained a number of toxins, opioids, and concentrated alcohol, marketed to mothers, children and the elderly. Most of the medicines’ formulas were hidden or completely fabricated, making it impossible for the ill and sickly to make informed medical decisions. The culture of patent medicines was a dangerous one. They preyed on the easily manipulated and desperate in order to make a quick profit, all under the guise of being genuine medication.

Harrison Dressler is an Arts student entering his second year at UNB and worked as a summer student in the Microforms Unit.

Recommended Secondary Readings

P.S. Brown, "Female Pills and the Reputation of Iron as an Abortifacient, " Medical History 21, no. 3 (1977).

"The Composition of Certain Secret Remedies. Viii. ‘Female Medicines.’" The British Medical Journal 2, no. 2449 (December 07, 1907).

T. E. C., Jr, " WHAT WERE GODFREY'S CORDIAL AND DALBY'S CARMINATIVE?" Pediatrics 45, no. 6.

Peter G. Homan, "Daffy: A Legend in His Own Preparation," Pharmaceutical Journal (December 23, 2006).

"The Medical Men of Saint John in Its First Half Century." Blog of johnwood1946.

Jennifer Welsh, "Dr. James Fever Powder," The Scientist Magazine (October 1, 2010).

Add new comment