- Submitted on

- 3 comments

Nova Scotia was one of the thirteen colonies which remained in the British fold during the American Revolution. Within the province, there existed a stark divide in sentiment, in particular between urban and rural inhabitants. Halifax was the focal point of British support, but the out ports, communities like Liverpool, which were further removed from the influence of the capitol, were much more fluid in their opinions. Observers all along the coast of Nova Scotia were trying to make sense of this change in status quo, including a man named Simeon Perkins. Perkins, a notable figure in the study of the Atlantic World, though surprisingly forgotten in the study of the American Revolution, was recording the events as he witnessed them in a diary which would eventually total over twenty, hand-written volumes and span almost fifty years.

Born to a merchant family from Norwich, Connecticut in 1735, his father, in-laws, brothers, uncles and other relatives earned their livelihoods by trade. After the death of his first wife, he moved to Liverpool in 1762 as part of the Planter movement in hopes of setting up a trading business. Perkins struggled during his early years in the province; at one point, he returned to Connecticut because of the dire financial situation of trade in the region, however, by the 1770s, his business was firmly established in his adoptive hometown as was his proclivity for keeping his diary.

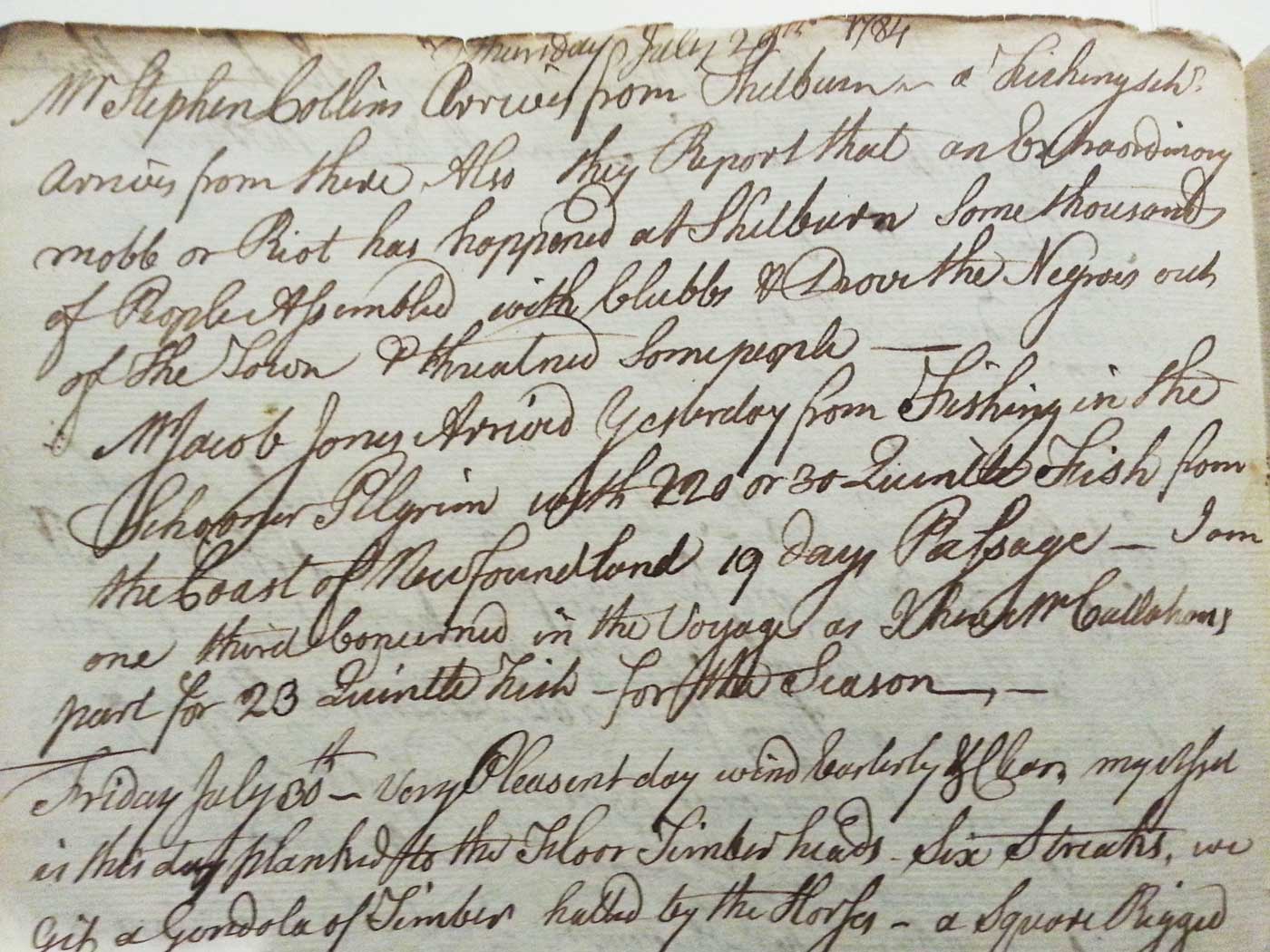

The Diary of Simeon Perkins is an invaluable tool for understanding life in rural Nova Scotia during the 18th and 19th centuries. Perkins started keeping his diary in 1766 and by 1774, he made almost daily entries, a habit which he continued until the month before his death on May 9, 1812. Owing to the political, military, and judicial posts which he occupied over the course of his life, the Perkins diary offers a unique perspective in what daily life was like in rural Nova Scotia, including insight into what people thought about the American Revolution. Perkins’ diary allows readers to challenge what they think they know about Nova Scotia and its place during this pivotal event.

Perkins primary occupation during the American Revolution was that of a merchant, magistrate, and politician, but as the war came closer and closer to Liverpool, Perkins assumed a new roll, that of privateer. Perkins entered this particular business venture in 1779 in partnership with several other Liverpool merchants who felt that the province and the Royal Navy were not doing enough to secure the town. While privateering was typically intended to interrupt enemy shipping, it could also be used as a means of defense, which is what happened in Liverpool; it allowed the merchants of Liverpool a chance to fight back against American raiders.

At first, Perkins sympathised with the rebels and it was not until he suffered his fourth privateer loss that he started to show any anger towards his American brethren. For Perkins, loyalism was not a cut and dry question but rather one which was informed by his war time experience. Many like Perkins were not loyalists because they were die- hard supporters of King George, the “G-d Save King George” loyalist which has become part of the creation story of modern Canada, but rather because there were more advantages to be had by remaining attached to the British Crown. Simeon Perkins’ loyalism afforded him military protection for his home and business interests against American privateers which frequently raided the communities along the South Shore of the province. Once the war was over in 1783, Perkins almost seamlessly resumed his trade and his communication with family and friends in the newly formed United States of America, as if nothing had changed. War-time interactions were forgotten and there was money to be made in trade with this new nation.

The discussion of the loyalism of Simeon Perkins raises the question of how does one define the term “loyalism” and “Loyalist”? Can there be degrees of loyalism? Can loyalism be on a continuum? Can loyalism be coercive in nature or, must loyalism be concrete in order to be authentic? Perkins and his diary serves as a reminder that loyalism wasn’t and shouldn’t be viewed in one single- faceted way but rather something which was unique to person and to each group of people. It’s essential to use the unique cases of specific individuals when we are presented with them in order to paint a broader and more accurate picture of history.

Recommended Sources

John Bartlet Brebner, The Neutral Yankees of Nova Scotia : A Marginal Colony during the Revolutionary Years, (Toronto: McClelland and Stewart, 1969).

Robert M. Calhoon, "The Loyalist Perception," Acadiensis 2, no. 2 (1973): 3-13.

C. Bruce Fergusson, “PERKINS, SIMEON.” In Dictionary of Canadian Biography, vol. 5, (University of Toronto/Université Laval, 2003).

Simeon Perkins, The Diary of Simeon Perkins, Vol. 1 and 2, (Publications of the Champlain Society: Toronto, 1948).

Patricia Rogers, “The Loyalist Experience in an Anglo- American Atlantic World,” In Planter Links: Community and Culture in Colonial Nova Scotia, edited Margaret Conrad and Barry Moody, (Fredericton: Acadiensis Press, 2001).

____________, “Loyalist Expectations in a Post- Revolutionary Atlantic World,” In The Nova Scotia Planters in the Atlantic World, 1759- 1830, edited T. Stephen Henderson and Wendy G. Robicheau, (Fredericton: Acadiensis Press, 2012).

Robyn Brown is a high school teacher from Nova Scotia and is a second year MA student at Dalhousie University.

Comments Add comment

Simeon Perkins journal -- quality of transciption?

Perkins transcription

Hello Dr. Bell, We can refer your question to the author of this blog post, but the Queens County Museum in Liverpool, Nova Scotia is likely the authority, as they hold the original diary and offer portions scanned on their website: http://queenscountymuseum.com/perkins-diary/

Thanks for your comment!

Further information

Out of the volumes of transcribed diary, it's actually the Innis volume (vol. 1) which we know has been edited for content- in the forward he states that he purposely removed entries which were not related to Nova Scotia.

The Harvey- Fergusson editions have entries missing as well but from what they said in their forward, they were minor entries ("Nothing of Note" or things related to the weather). It should be noted that the Harvey Fergusson vol. 2 is significantly longer than Innis vol. 1, longer forward/ intro, more footnotes, and a shorter time period, just longer, given that it covers a shorter time period.

Add new comment Comments