- Submitted on

- 8 comments

In this special edition of Lost Loyalists you will learn about five amazing women’s lives during the American Revolution. Loyalist women are often under-researched as they did not typically participate in the war as part of the military, but that does not mean that they did not have an impact on its outcome. These women have fascinating stories, and I am happy to share them with you.

The only surviving sources for women often are Audit Office claims that have been put in for them (or by them) because they were widows. However, some of these extraordinary women were never married and were loyalists because they personally helped in the British war effort.

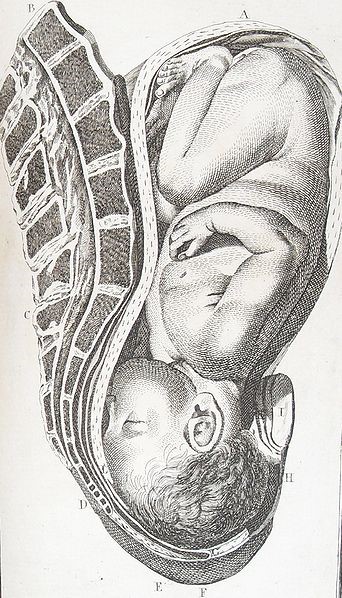

1. Janet Cumming was living in Charleston, South Carolina when the American Revolution began. She was a widow, and a native of Scotland. She was also a midwife—a profession she had practiced for many years before this war began and where she would earn £400 sterling per annum. Her midwifery fees were £40 for white women and £10 for black women. Her daughter and son-in-law were forced to leave Charleston because of their British sympathies, and in 1777 Cumming followed them back to England. Cumming claimed to have lost £2,600, but was not compensated because her claim was disallowed for want of proof.

(Image Courtesy of Wikimedia Commons, found on archive.org)

2. Lorenda Holmes was a native of America and she lived for many years with the family of Jacob Walton (who eventually became a loyalist). Holmes is a fascinating figure because she helped sneak letters off of the ship Asia to assist the loyalist cause in New York. After doing this for some months, she was seized by a Mr. Gibbs—a member of the Committee of Safety. Gibbs then forced her to take off all of her clothing to find any hidden letters and exposed her in a drawing room to a mob. In her claim she writes that thousands watched her being paraded naked, but often people exaggerated in claims. Nonetheless, this was a traumatic experience for Holmes. After this disturbing event, Holmes went to Mrs. Mortier’s home in Greenwich, Connecticut where her aunt also lived. General Washington was also housed there, and because plots against him were frequently suspected, Holmes and her aunt, now prisoners in the home, were once accused of poisoning Washington’s peas. Holmes and her aunt were forced to eat the presumed poisoned peas and survived. After this event, Holmes and her aunt escaped and were able to find a passage to England thanks to Henry Cruger.

(Great Britain, Audit Office, Claims, American Loyalists : Series I (AO 12) : 1776-1831, AO12/30/338)

3. Eleanor Lestor, from South Carolina, was a native of Ireland. She immigrated with her husband in 1770 to Charleston. Together, they kept a shop where they sold liquor for the entertainment of sailors. They also owned seven or eight slaves. Eleven months after their arrival her husband was killed by “some blacks”; Lestor kept the business going until her shop was destroyed by a fire in January 1778. In 1780, she said that she was the first to welcome British troops in Charleston, and that she even harboured some British sailors in her home. She estimated her wealth at £80,000 in local currency when she returned to England in 1782 with one slave.

4. Margaret Locke was from Pennsylvania. She claimed to be the wife of Captain Josiah Locke of General Skinner’s Corps who had left her with a small child; however, a German woman that she later lived with told the Commissioner that Margaret was not married to Locke. In her claim, Locke writes that she had given intelligence to the British while they were occupying Philadelphia and that this information helped capture a spy.

5. Sarah McGinn (maiden name Cass) was from New York. Her husband, Timothy, was killed during the French and Indian War. When the American Revolution began, McGinn and her son George were living on her father’s property in Mohawk River in Tryon County, New York. Because she spoke an indigenous language, the Whigs (or Patriots) demanded that she act an interpreter, which she refused. Because she would not work under the Patriots, she was held under suspicion of acting for the British. After this incident, McGinn travelled to Fort Stanwix, and under Sir John Johnson she was sent into Indian County to do work for the British. Her son George was wounded while also serving as an interpreter under the “Indian Department.” She appeared to have another son who was deemed insane who had been confined in chains for several years; she abandoned him when she left Fort Stanwix. Years after his mother left him, he was burned alive.

(Image courtesy By NPS Photo [Public domain], via Wikimedia Commons)

Annabelle Babineau was a student assistant at the Harriet Irving Library. She is entering her first year of the English Masters Programme at UNB.

Comments Add comment

Lorenda Holmes

Lorenda Holmes

Good morning, and thank you for your interest and kind offer. We have excerpted one of Holme's claims in the above article. Is this the same claim you have transcribed? We do hold a copy in our collections. Claims are such a treasure trove of information!

Lorenda Holmes

More info on Lorenda Holmes

Hello, thank you for your comment. We only did basic research on Lorenda Holmes, so we have not collected any other information on her. If you are in the Fredericton, New Brunswick area, you are welcome to come and do further research in The Loyalist Collection.

Loyalists in North Carolina

North Carolina Loyalists

Hi, thank you for your question. Do you know if she submitted a claim to the commission set up by the British government to compensate loyalists? If you know the town/city/village where she lived, contacting a local historical organization is often useful or searching archive.org for an early history written on the community.

Who is the author?

Author of blog post

Hi, thanks for your interest in our blog, Atlantic Loyalist Connection. You will find the byline of the author at the bottom of the entry, Annabelle Babineau.

Add new comment Comments