- Submitted on

- 2 comments

Volunteers of Ireland

The second Irish-based regiment was also raised in Philadelphia and New York during 1777 under the Northern Irish commander Colonel Francis Lord Rawdon. General Sir Henry Clinton, writing in a letter to Lord George Germain in October 1778 regarding the idea for the formation of the Volunteers of Ireland realized the antipathy many Irish felt towards the British government. He stated that, “The Emigrants from Ireland were in general to be looked upon as our most serious Antagonists. They had fled from the real or fancied Oppression of their Landlords. . . To work up on these latent Seeds of national Attachment appeared to me the only Means of inciting these Refugees to a measure, contrary perhaps to the particular Intrests of most of them. On this ground I formed the Plan of raising a Regiment whose Officers as well as Men should be entirely Irish.” A recruiting notice was printed in the The Royal Gazette, New York on May 9, 1778 proclaiming that, “ALL Gentlemen, Natives of Ireland, who are zealous for the Honour and Prosperity of their Country, are hereby informed, that a Corps, to be st[y]led the VOLUNTEERS of IRELAND, is now raising by their Countryman, LORD RAWDON.”

This regiment would be staffed primarily with regular officers, so to avoid the issues that had arisen with the discipline-lacking of the Roman Catholic Volunteers, particularly since the regiment recruited 380 deserters from the Continental Army by October 1778. The use of deserters was explained in a letter from Lord Rawdon to Major John André written on May 21st, 1780 which revealed that, “The great proportion of Irish in the Rebel Army & their constant desertion from those Provincial Corps into which upon their coming over to the British Troops they were generally enlisted, made it appear advisable that a national Regiment should be formed; which might not only instigate them to quit the opposite party; but also, by retaining them, draw service to the King.”

(Public Domain via Wikimedia Commons)

The regiment would quickly prove to be a military asset the British. By June 1778, the Volunteers of Ireland had participated in the Battle of Monmouth Courthouse in New Jersey, followed by the Mathew-Collier Raid in Portsmouth, Virginia in May 1779. The regiment was then sent to Charleston, South Carolina in December 1779 where they fought with distinction. The Volunteers were participants in the Siege of Charleston in April 1780, fought at the Battle of Camden (South Carolina) with General Cornwallis on August 16, 1780, and at Hobkirk’s Hill (Camden, South Carolina) under Lord Rawdon on April 25, 1781. They had been placed on the American establishment as the 2nd American Regiment on May 2, 1779 and were then taken into the British Army as the 105th Regiment of Foot on December 25, 1782. In August 1783 the regiment—mainly composed of officers at this point—went to Ireland, then were officially disbanded in England 1784. Near the end, veteran soldiers of the regiment had also been sent to provincial regiments in Charlestown, particularly the Prince of Wales American Regiment, New Jersey Volunteers, and DeLancey’s Brigade, many of whom were shortly resettled in the region which later became the Maritime Provinces of Canada.

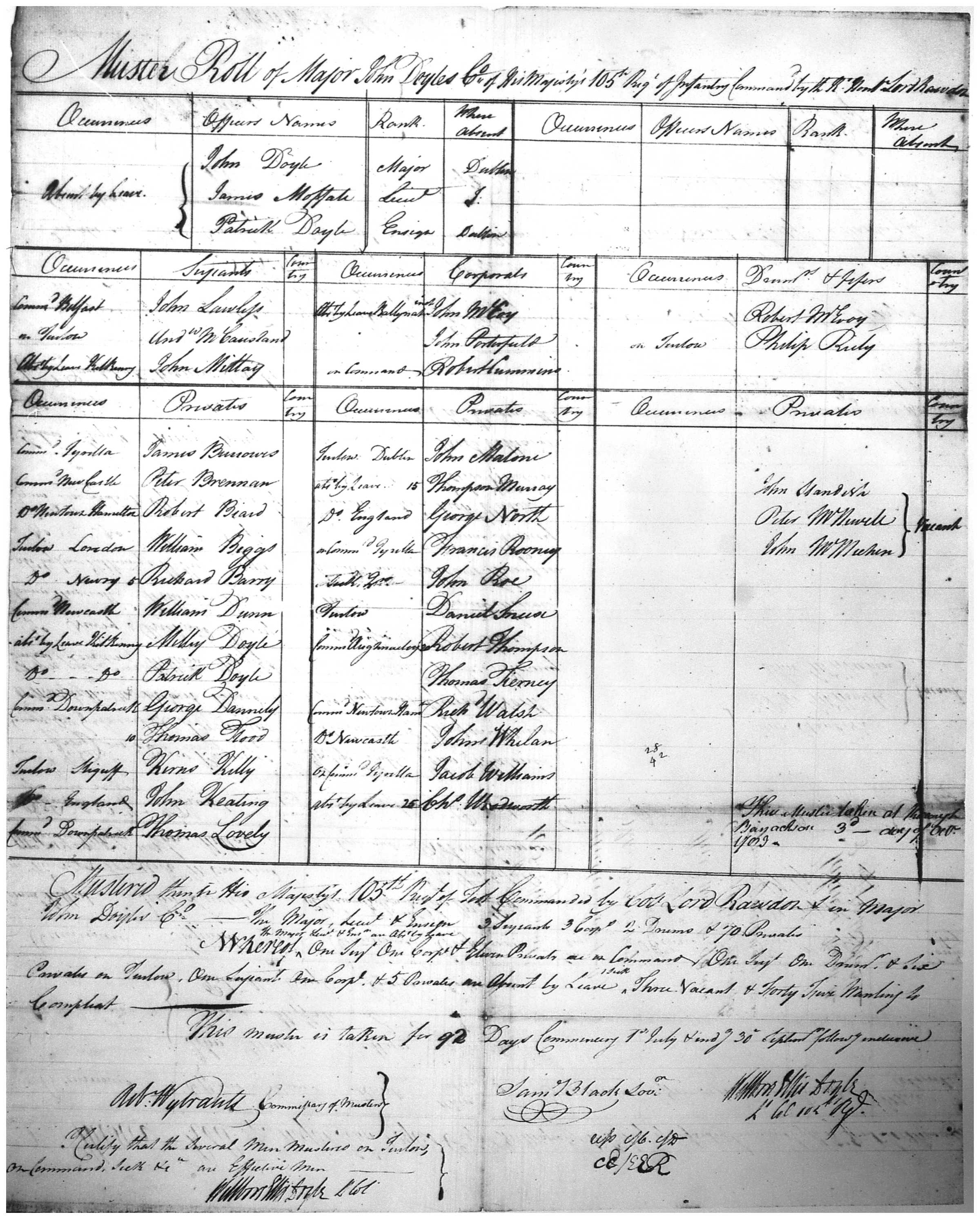

An example of a possible career of an Irish Catholic loyalist soldier can be found by following a name through a trail of muster rolls: Patrick Donnelly. He first appears in the rolls of the Roman Catholic Volunteers from 1777 to 1778, then in the Volunteers of Ireland from 1779 to 1782 (see the Index from Library and Archives Canada for the British Military and Naval Records). The name next shows up amongst the ranks of the Prince of Wales in 1783, followed by appearances in land petitions from veterans of that regiment in St. John County and York County, New Brunswick. There is the possibility that it was more than one “Patrick Donnelly” who generated these records, but the dates on the documents do follow a plausible timeline.

(Great Britain, War Office, Muster Books and Pay Lists (WO 12/9967): 105th (Volunteers of Ireland) Regiment of Foot: 1782-1784, 1794-1795, The National Archives)

Although on the surface, early Irish Americans, particular Irish Catholics, would not be an obvious population from which to draw loyalist military support in the colonies; they did, however, form the basis for two provincial regiments, one a failure, and one which became an accomplished unit. The Irish role in the American Revolution merits more in-depth investigation to untangle the complex pressures at work in ethnic, religious, and national allegiances.

See New Brunswick Loyalist Journeys story maps for the biography of an officer of the Roman Catholic Volunteers, Samuel Richard Wilson.

Select Secondary Sources

Todd Braistead, The On-Line Institute for Advanced Loyalist Studies.

Rene Chartrand and G.A. Embleton, American Loyalist Troops 1775-84, Oxford: Osprey, 2008.

Harry T. Dickinson, “Why did the American Revolution not spread to Ireland?,” Valahian Journal of Historical Studies Vol. 18-19 (2012-2013), pp. 155-180.

Leroy V. Eid, “’No Freight paid so Well’: Irish Emigration to Pennsylvania on the Eve of the American Revolution,” Eire-Ireland Summer 1992, Vol. 27 Issue 2, p35-59. 25p.

A.W. Haarmann, “The Roman Catholic Volunteers, 1777-1778,” Journal of the Society of Army Historical Research 49 (1971), pp. 184-185.

Philip R.N. Katcher, King George's army, 1775-1783: a handbook of British, American and German regiments, (Reading : Osprey Pub., 1973).

Robert Kee, Ireland: A History, London: Abacus, 1998.

J. S. McGivern, “Catholic Loyalists in the American Revolution: A Sketch,” CCHA Study Sessions, 48 (1981), pp. 91-99.

Neil York, “American Revolutionaries and the Illusion of Irish Empathy,” Eire/Ireland Vol. 21, 2, (Summer 1986), pp. 13-30

Leah Grandy holds a PhD in History and works as a Microforms Assistant at the Harriet Irving Library.

Comments Add comment

Irish catholic loyalists

Irish Catholic Loyalists

Thank you for your comment. Indeed, neither side of the Atlantic was a hospitable place in the Revolutionary period for Irish Catholics.

Add new comment Comments