- Submitted on

- 0 comments

Often, we can only guess at what children of the past experienced in their young lives as it was not usual for them create documents of their own. This was poignantly true for the children of the African Diaspora during the eighteenth century. A record as basic as a name, however, can offer a way into an historical culture. The Book of Negroes holds the names of many children leaving New York City at the end of the American Revolution, although an equal number of children's names were not put to paper at this time.

Children of African descent are one of the most difficult subgroups to uncover in the eighteenth-century Atlantic World. Most studies of enslaved children and children of African descent in North America and the Caribbean pertain to plantations in the West Indies and Southern United States just prior to the American Civil War, thus any contribution to understanding the history of childhood among this group must be approached with a creative use of primary sources.

An examination of the cohort of children who were born during the American Revolution and the period immediately before the outbreak of war (1773 to 1783) demonstrated the range of life experiences among peoples of African descent living in North America. Of the children found in the Book of Negroes, some were enslaved, some were born enslaved but escaped slavery and gained a marginal freedom, and some were born free due to their parent’s leaving former masters. More background information on the Book of Negroes is available in the post “The Importance of the Book of Negroes.”

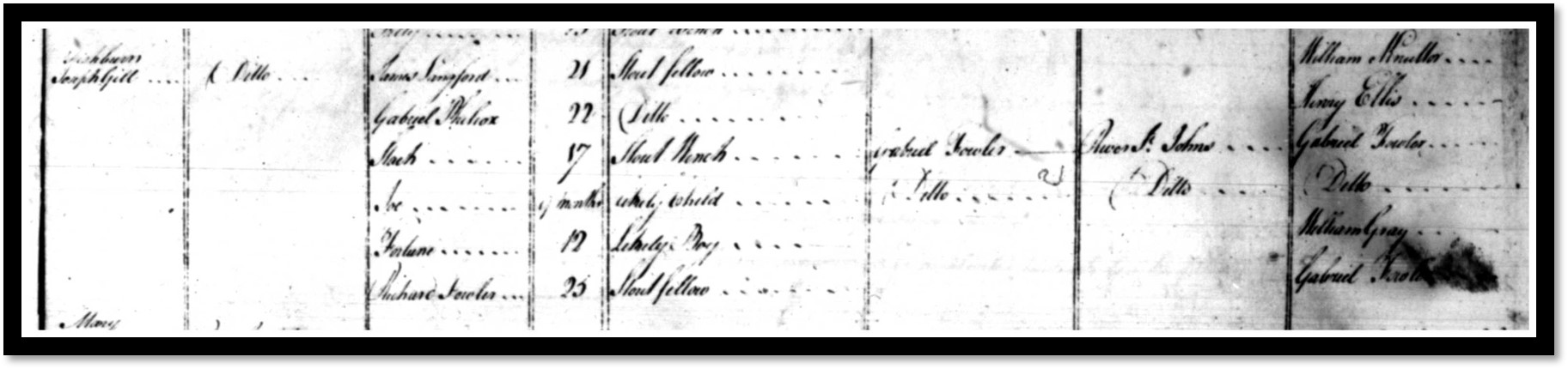

(Guy Carleton, 1st Baron Dorchester, British Headquarters Papers: 1747-1783)

The question of what defines a child needs to be addressed, and certainly childhood by the current North American definition did not exist for many people of the African Diaspora. For the purposes of this study, all individuals born between 1773 and up to and including 1783 have been profiled, or ten years old and younger as of the time the Book was produced. In total, the book recorded around 3,000 individuals including 900 women, over 1300 men, and 750 children. However, about half of the children remained nameless, so could not be included in a study examining names. Of the named children, there were 157 boys, 175 girls, 10 of unknown gender, and 342 in total, allowing for a gendered analysis as well. For an overall analysis of names in the Book of Negroes, see “Naming Culture in the Book of Negroes.”

|

|

Top Adult Female Given Names in the Book of Negroes |

Top Child Female Given Names in the Book of Negroes |

|

1 |

Nancy |

Sally |

|

2 |

Sarah/Sara |

Betsey/Betsy |

|

3 |

Hannah/Hanna |

Jenny |

|

4 |

Mary |

Sarah |

|

5 |

Dinah/Dina |

Sukey/Suky |

|

6 |

Betsey/Betsy |

Nancy |

|

7 |

Sally |

Mary |

|

8 |

Jenny |

Dinah, Fanny, Hannah, Judith, Polly |

|

9 |

Jane |

---------------------- |

|

10 |

Phillis |

---------------------- |

Comparison of most frequently found female adult first names versus child first names from the Book of Negroes. Nicknames in italics.

Gender and Names

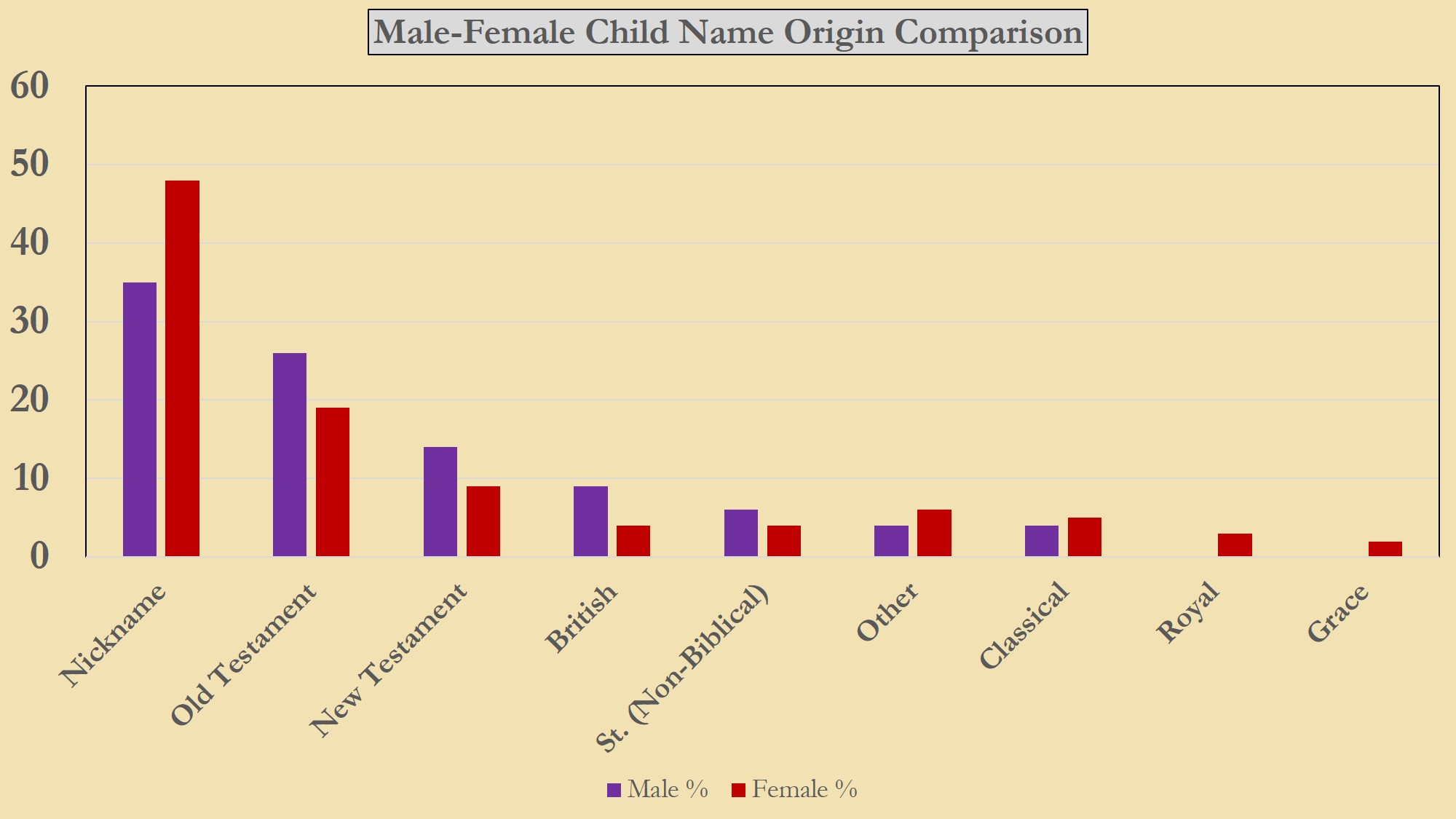

The practice of recording nicknames as formal names was found throughout the Book of Negroes but was especially evident among women and children. Female children had the highest usage of nicknames as formal names, likely indicative of their low status in the society of the British Atlantic World which made it an acceptable norm. Old Testament names were not as common among girls as the overall group, with New Testament names being used with more frequency.

|

|

Top Adult Male Given Names in the Book of Negroes |

Top Child Male Given Names in the Book of Negroes |

|

1 |

John |

John |

|

2 |

James |

Sam |

|

3 |

Thomas |

James |

|

4 |

William |

Harry |

|

5 |

Peter |

Peter |

|

6 |

George |

Abraham |

|

7 |

Jack |

David |

|

8 |

Samuel |

Jack |

|

9 |

Robert |

Billy, Dick, George, Joe, Robert |

|

10 |

Henry |

----------------------- |

Comparison of most frequently found male adult first names versus child first names from the Book of Negroes. Nicknames are in italics.

New Testament male names are the most common type of name origin. Boys more frequently than men had nicknames as their recorded formal name, assumedly demonstrating their lower patriarchal position.

(Male- purple, female- red)

In a comparison between male and female children’s names, girls (red) have a significantly higher instance of nicknames (48% versus 35%), while boys (purple) have a higher instance of Biblically derived names and, also a greater use of British names. As in many Atlantic World cultures—where the maintenance of paternal lineages is demonstrated through more stable and traditional naming practices—girls showed more diversity in name origins then boys, although the exact same number of unique names was used between the two genders of children.

Born Free or Enslaved

The status of an individual—born free, enslaved, formerly enslaved, or escaped—may also have had an impact on the name carried, or indeed on how a name changed over time. Also, it is important to note that the designation “free” was not a firm status for those of African descent in the Atlantic World and was a precarious state of which to keep hold.

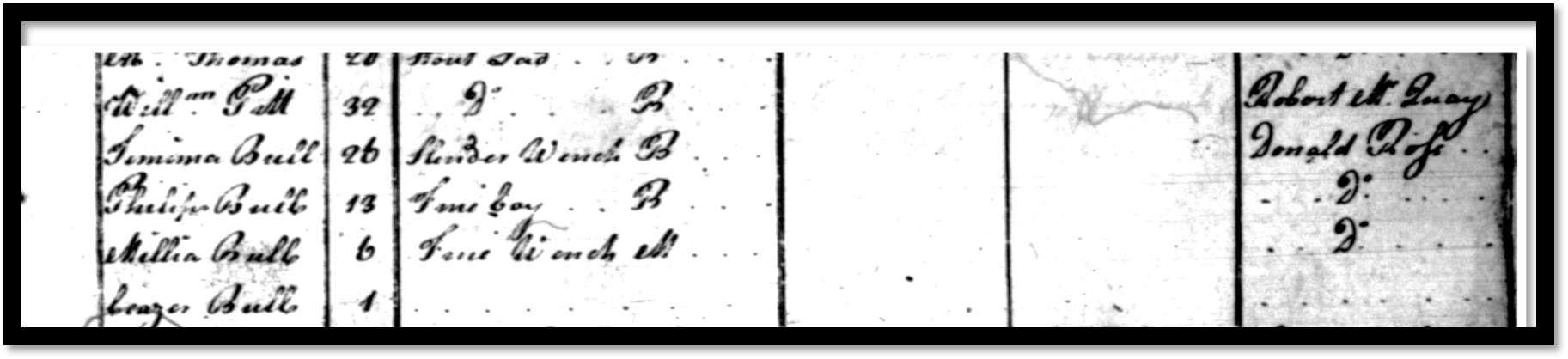

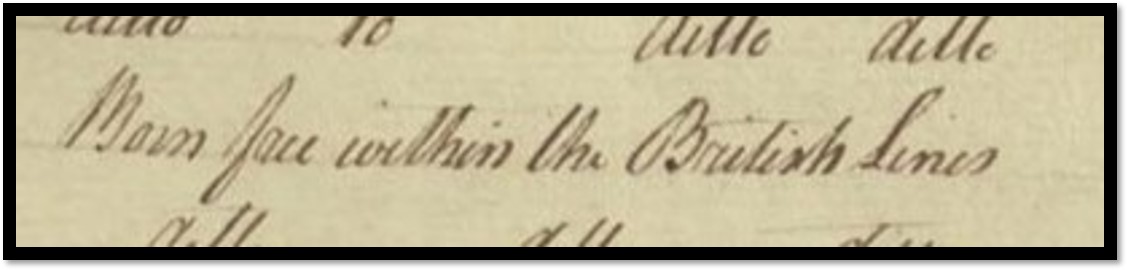

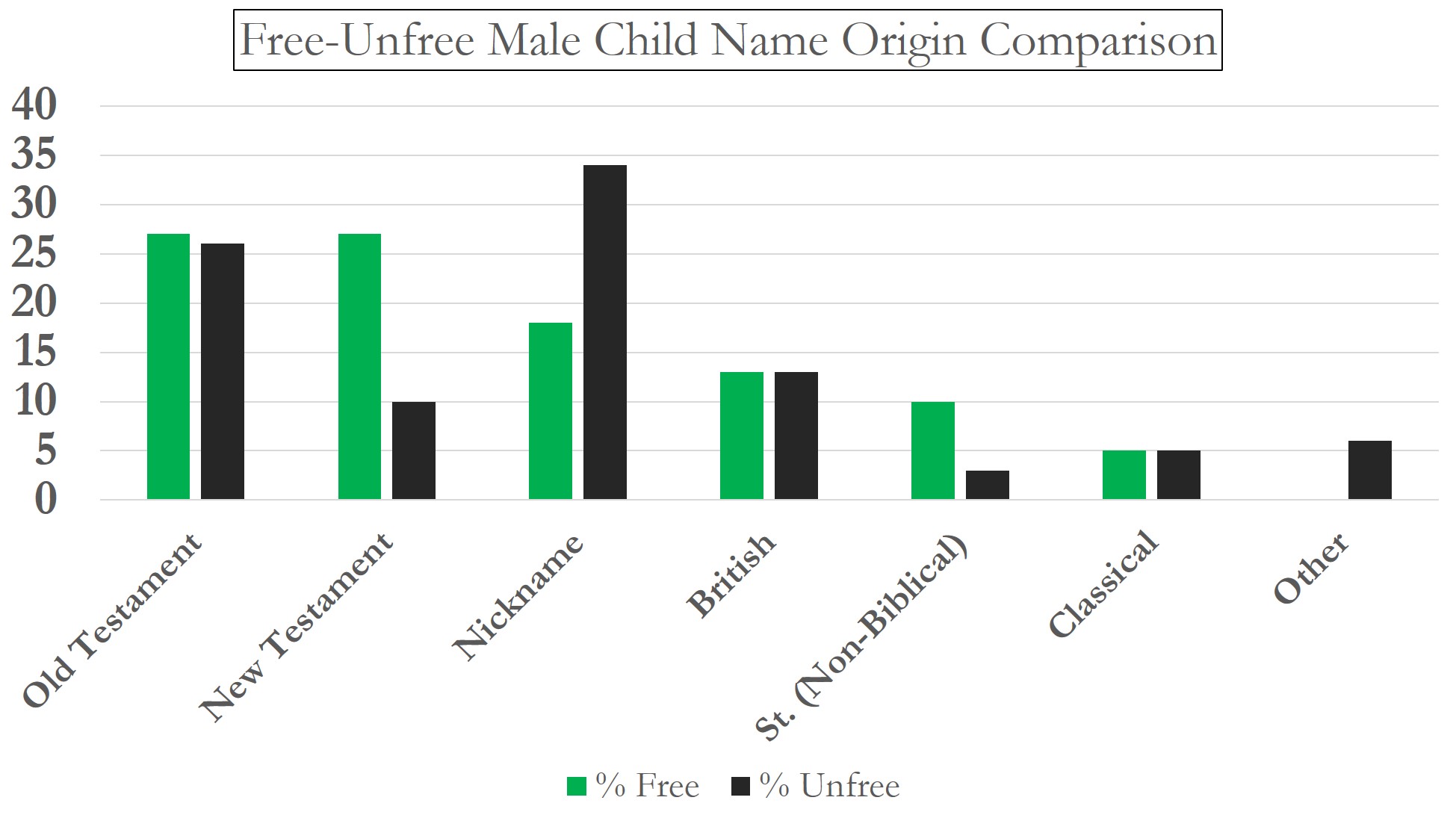

An important subgroup among children in the Book of Negroes were those recorded as being “born free within British lines” after their parents had achieved a type of freedom by leaving their former masters and joining the British forces. Another group under the heading “unfree” included those who were enslaved at the time the record was made or had been named while enslaved. Differences appeared in the types of names chosen for children who were born into freedom versus those who were enslaved.

(Free- green, unfree – dark green)

The pattern which emerged showing a difference in naming according to whether the child was free or enslaved was the increased use of New Testament names and a decrease in the use of nicknames as formal names. Among boys, this pattern was most pronounced: free boys had many more New Testament names (27% free versus 10% unfree) and the unfree more nicknames (18% free versus 34% unfree). This new pattern was associated with children who were born after their parents left enslavement, marking a new phase in family and individual lives.

The Children

Looking at a group through statistics can be dehumanizing and is best combined with biographical work to look at patterns through individual lives as well. Hints of families, both new and old, can be gleaned by looking at how the names of the children in the Book of Negroes were recorded and who they were with. There were a range of situations: enslaved to owners; indentured; and with their mothers, fathers, or an extended family.

The above example lists Stach, who was a seventeen-year-old mother, with Joe, her nine-month-old baby. They were enslaved to Gabriel Fowler, a New York loyalist. Fowler’s first wife had died, and he bought Stach to look after his young son. Stach and Joe were the first enslaved people in the Hammond River, Kings County, New Brunswick area, an instance in which the events of the American Revolution did not allow a move away from enslavement.

An examination of the names of children through the Book of Negroes raises questions of agency, autonomy, and expression in the colonial Atlantic World. Perhaps the increase in the number of New Testament names symbolically embodied the journey of the Jews of the Old Testament from enslavement to freedom and a new hope. The measure of freedom gained by some people of the African Diaspora through the struggles of the American Revolution and later migrations was a significant event in their lives. The distinctive cultural naming pattern which appeared among children “born within British lines” registered the importance of the possibilities of freedom.

Leah Grandy holds a PhD in History and works as a Microforms Assistant at the Harriet Irving Library.

Note: This post is modified from a presentation made to the meeting of the Atlantic Medieval and Early Modern Group at Kings College, Halifax, Nova Scotia in October 2019. I thank the audience members who participants in the panel for their feedback.

Add new comment