- Submitted on

- 2 comments

The naming of an individual can offer insight into the worldview of the name giver, including perspective on their religious, national, ethnic, and gender identities. The culture of people of African descent in North America during the eighteenth century is particularly difficult to research using the standard historical record because of their lack of representation among written documents. The record of names which exists in the document known as the Book of Negroes offers a chance, however, at insights into a particular group ethos and a developing culture.

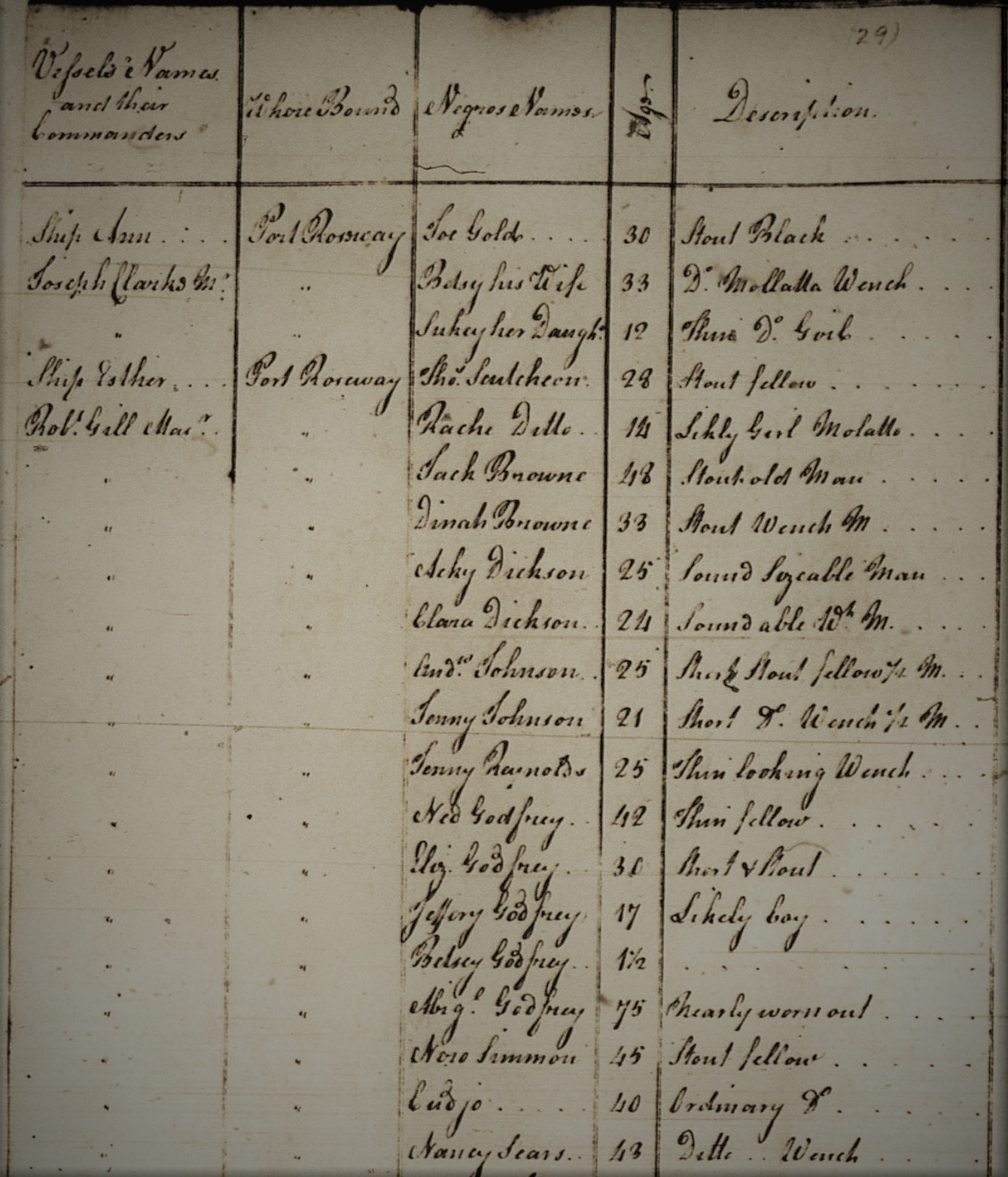

The Book of Negroes provides a rich source of information on a variety of people of African descent living in New York at the end of the American Revolution—both free and enslaved. The people in the Book were recorded in the largest numbers from Virginia and South Carolina; but also New York, New Jersey other areas of New England; Georgia; and the Caribbean. Most were formerly enslaved before the war and had been granted freedom by the British government for escaping from their former American colonial masters. This subgroup left New York as loyalists because of their chosen allegiance to the British Crown. A significant portion of people listed in the Book of Negroes were free born, but a large segment also remained enslaved to loyalists of European ancestry and accompanied them to the Maritimes and other parts of the Atlantic Word. Therefore, freeborn, formerly enslaved, and currently enslaved people are all recorded in the Book of Negroes.

The naming trends which emerged from an initial sampling of approximately 30% of the total circa 3,000 individuals listed in the Book included the appearance of classical names, city names, African “day” names, a high incidence of nick names as formal names, and the common use of Old Testament names.

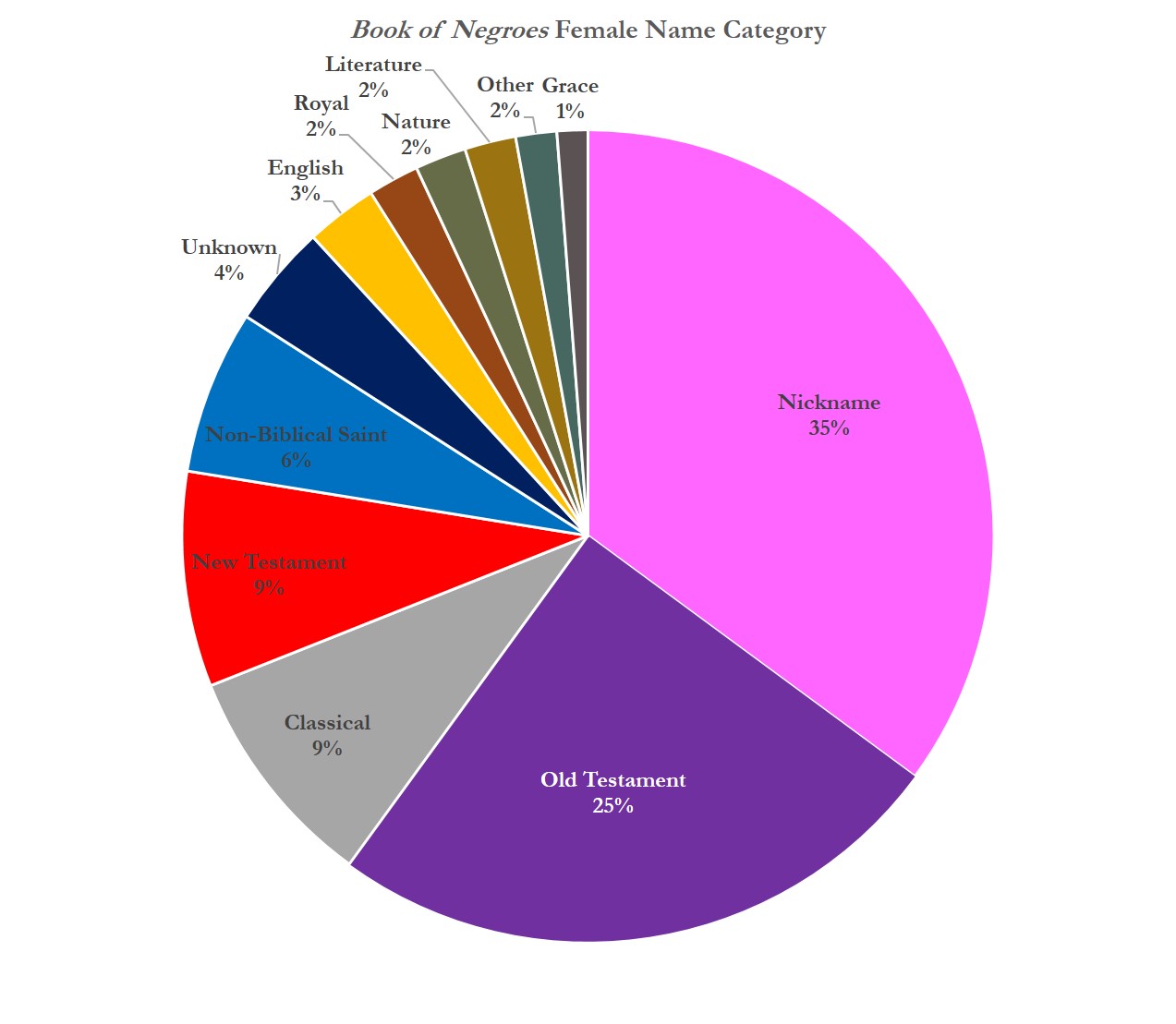

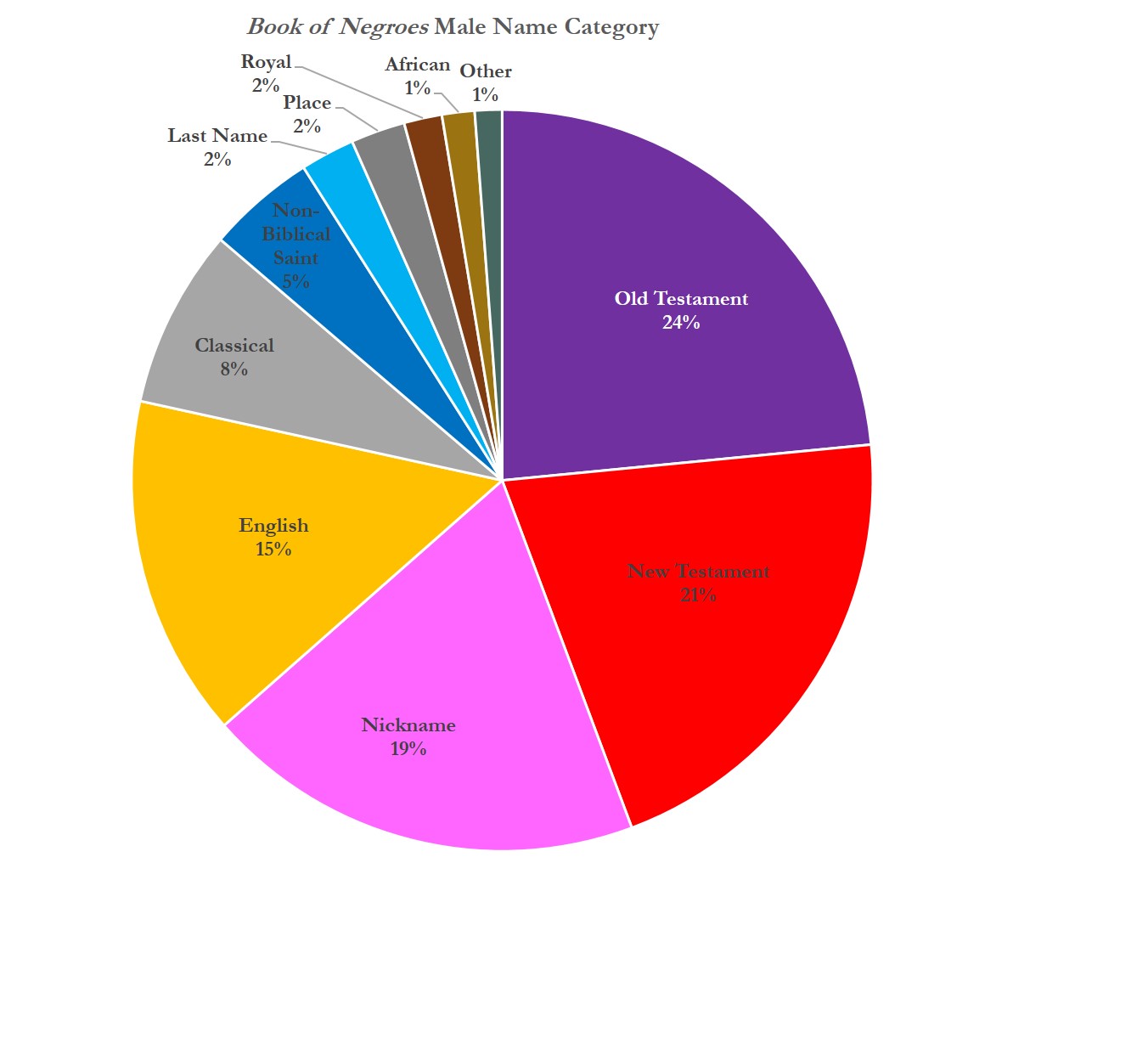

The tradition of giving classical names, following with the Eurocentric trend of Neoclassicism, to enslaved people in North America and Caribbean, was common during the beginning of the trans-Atlantic slave trade and was most often done to individuals who already had names prior to their enslavement. Names drawn from the Greco-Roman world and mythology in later generations became part of the traditional naming pool used by enslaved people in America with their own children, often to honour ancestors. The most frequent classical names that appeared in the Book of Negroes were: Phillis, Venus, Chloe, Silva, and Lucretia; Anthony, Ceaser, Cato, Pompey, Scipio, Nero, and Bacchus.

Another category of naming associated with enslaved people in America was the use of cities as names, particularly British cities, as given names for males such as Bristol, London, Dublin, Boston, and Glasgow.

Much of the secondary literature on names among enslaved people has concentrated on the use of African “day” names. In Western Africa, many cultures bestowed names according to the day of the week on which a person was born. The most commonly used African day names were still found in the Americas well into the nineteenth century, although these names were often divorced from their original use and origin. This did, however, form a historical and cultural link beyond the Middle Passage. Cudjo, Cuff/Cuffie, and Mingo were the most common day names, with a few likely changes of female African names to European names, such as Phibba to Phoebe (which was also classical) and Juba to Judah and Judith, but they were not found in such large numbers in contrast with male names.

|

Top Ten Female Names |

Top Ten Male Names |

||

|

1 |

Nancy |

1 |

John |

|

2 |

Sarah / Sara |

2 |

William |

|

3 |

Dinah / Dina |

3 |

Thomas |

|

4 |

Mary |

4 |

Jack |

|

5 |

Betsy / Betsey |

5 |

James |

|

6 |

Sally |

6 |

Samuel |

|

7 |

Sukey |

7 |

George |

|

8 |

Hannah / Hanna / Hana |

8 |

Peter |

|

9 |

Phillis |

9 |

Joseph |

|

10 |

Jenny |

10 |

Charles |

Top names by gender drawn from the first third of the Book of Negroes.

One of the strongest patterns in naming among individuals in the Book of Negroes was the high occurrence of nicknames as recorded, formal names. This practice did not exist among the contemporary, colonial male population of European descent, and only occasionally among women of European descent in the Maritime region. The practice was, however, especially evident among women in the Book of Negroes, as nicknames make up half of the top ten names (Nancy, Betsy, Sally, Sukey, and Jenny), while only one appears on the male top ten (Jack). Other common nicknames used in the Book included Peggy, Nelly, Sam, Dick, Ben, Billy, and Harry. It is likely indicative of people of African descent recorded in the Book of Negroe’s status in society which made it an acceptable norm to record nicknames formally.

(Public domain, via Wikimedia Commons)

Old Testament names were particular prevalent among female Black Loyalists, especially Sarah, Hannah, Rachel, Abigail; and Isaac, Jacob, Moses, David, Samuel, Abraham, and Job among men. The most common Old Testament names used were those of important figures in the story of the Jewish people, as enslaved people likely perceived a parallel in their own stories to those of the Bible as Christian traditions became integrated into their cultural practices. An Old Testament name of prominence among people of African descent in North America was Dinah, which became a synonym for an enslaved, black woman in America by the nineteenth century.

Nicknames made up the largest category of female names in the Book of Negroes, followed closely by those from the Old Testament. Among males, about half of all names were from the Old and New Testament, followed by nicknames in frequency. As with the general population, Biblical, non-Biblical saints, and traditional English names appear in high numbers. Both genders had a significant number of Classical names and non-Biblical saints’ names. Men had a large representation of traditionally English names, as well as an appearance of last names as first names, place names, royal names, and African names. In contrast, women had a smaller subset of royal, nature, and literary names.

The distinctive types of names and naming patterns found in the Book of Negroes show the influence of the experience of enslavement and the emergence of a new culture, such as in the names which were assigned initially by slave masters but were then claimed and used for later generations by the enslaved people within their families. The class position which people of colour held in broader North American society is also demonstrated in the way in which their names are recorded by British and American scribes. At the same time, the development of an autonomous culture within the institution of slavery and among the growing number of free people of African descent can been seen in unique naming practices.

Select Secondary Sources

Cheryll Ann Cody, “There was no ‘Absolom’ on the Ball Plantations: Slave-naming Practices in the South Carolina Low Country, 1720-1865,” The American Historical Review, Vol. 92, 3 (1987), pp. 563-595.

J.L. Dillard, “The West African Day-Names in Nova Scotia,” Names (American Name Society), Vol. 19, 4 (December 1971) pp. 257-261.

Jerome S. Handler and JoAnn Jacoby. “Slave names and naming in Barbados, 1650-1830,” The William and Mary Quarterly, Vol 53, 4 (1996), pp. 685-728.

John C. Inscoe, “Carolina Slave Names: An Index to Acculturation,” The Journal of Southern History, Vol. 49, 4 (1983), pp. 527-554.

Laura Alvarez Lopez, “Who named slaves and their children? Names and naming practices among enslaved Africans brought to the Americas and their descendants with focus on Brazil,” Journal of African Cultural Studies, Vol. 27, 2 (2015), pp. 159-171.

John Thornton, “Central African Names and African-American Naming Patterns,” The William and Mary Quarterly, Vol. 50, 4 (Oct. 1993), pp. 727-742.

Note: This post represents the preliminary results of a larger project concerning naming patterns in the colonial Maritimes.

Leah Grandy holds a PhD in History and works as a Microforms Assistant at the Harriet Irving Library.

Comments Add comment

Cool project!

Thanks!

Thanks very much, Rebecca!

Add new comment Comments