- Submitted on

- 0 comments

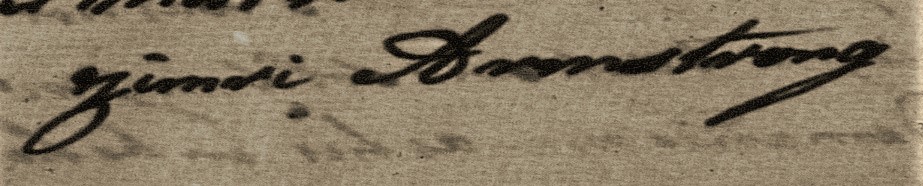

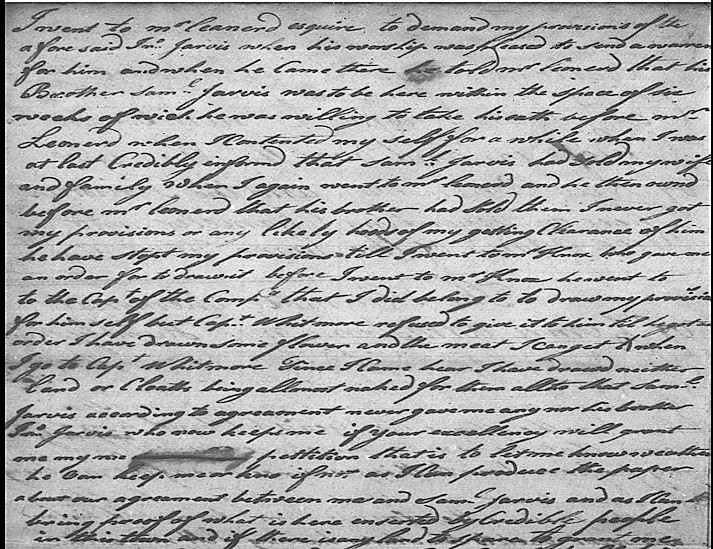

(New Brunswick, Surveyor General, Land Petitions: 1783-1834, “Memorial of Zimri Armstrong,” 20 June 1785)

Throughout the American Revolutionary War, the British government granted enslaved persons of colour their freedom in exchange for their service. The Philipsburg Proclamation issued on June 30th, 1779, by the British Army General Sir Henry Clinton, is one example of such. Accordingly, Zimri Armstrong served in the Revolutionary War and it would have been during this time that he would have been introduced to Samuel Jarvis. Samuel Jarvis, from Stamford Connecticut, fled to New York in 1776 and initially found employment with the commissariat – this department was in charge of supplying the British troops with food. Once the British evacuated out of New York, Jarvis was in charge of public accounts and papers; this position would eventually demand that he move to England. Presumably, this is when Armstrong indentured himself to the Connecticut Loyalist for two years on the condition that Jarvis would pay Armstrong and his family’s passage out of America, as well as establish him in a trade after the two years.

Jarvis, his young family and Armstrong travelled to Great Britain; however, shortly after the move, on July 12th, 1783, Jarvis was terminated from his position attending to public accounts and papers. Unlike his brother, William Jarvis, who remained in England, Jarvis decided to relocate to British North America, settling in Parr Town, present-day Saint John. However, Jarvis only remained in Saint John for one year, returning to Stamford, Connecticut. It is unknown as to Jarvis’s rationale to relocate. Since it is unknown as to whether Jarvis was successful in his petition for compensation, perhaps the British government’s negligence motivated his decision to return home. For example, Jarvis who “spent upwards of Nine years of the prime of His Days in faithfull Services to his King and Country, suffered much in Person & propery [property]” and expressed contempt that his father had left “Considerable property in Houses land &c none of which has been Confiscated & by the treaty of Peace [he] is prevented from any Enjoyment of it.” Another motivator for Jarvis may have been that the conditions in Saint John were poor, especially with his wife Elizabeth pregnant with their third child, Harriet Jarvis, compared to the prosperity familiar to Jarvis in Stamford. The situation was proving difficult for his sister, Polly, after recently resettling to New Brunswick, especially following her husband’s suicide. Whatever the reason, Jarvis left Armstrong behind “destitute of both Cloaths [cloths] and provisions in a Strange Country” only to complete the terms of his indenture with Samuel’s alcoholic brother, John Jarvis.

(New Brunswick, Surveyor General, Land Petitions: 1783-1834, “Memorial of Zimri Armstrong,” 20 June 1785)

Once Armstrong’s indenture was complete after two year, hoping that while in Connecticut, Samuel would be making the arrangement to free Armstrong’s wife and children, Armstrong he had still not received his provisions. From there, Armstrong proceeded to appeal to Samuel and John’s brother Munson Jarvis, who refused to give Armstrong “the vallue of one penny to support [him] when [he] was not able to support [him]self”. Accordingly, Armstrong appealed to a “Mr Leonerd” [Leonard]; perhaps Armstrong is referring to George Leonard, a Loyalist from Massachusetts, who served as a town director of Parr Town, responsible for the distribution of town lots. Mr. Leonard informed Armstrong that Samuel Jarvis, while in Connecticut, “had sold [his] wife and family.” One could not even imagine how betrayed Armstrong felt, exploited for his service only to receive no provisions and not any step closer to being reunited with his still-enslaved family. What would Armstrong do next? You can find out in our next post.

Isabelle Goguen is a student researcher for the Microforms Unit at the Harriet Irving Library. She is a graduate of UNBSJ with a Bachelor of Arts degree in English and History with a minor in Psychology.

Add new comment