- Submitted on

- 0 comments

Children suffering in any form will always cause a reaction from parents and making the right choice isn’t always easy. It was no different when Dr. John Jeffries inoculated children at the hospital on Georges Island near Halifax, Nova Scotia in the eighteenth century. In 2018, parents are fearful of giving their children vaccinations, just as parents were fearful of inoculation in the eighteenth century, but both of these practices can save children’s lives. A smallpox epidemic in Nova Scotia took place during the years of loyalist migration in the late 1700s; sickness was inevitable for most children in this period. During the American Revolution, Dr. Jeffries left Boston with the British army and moved to Nova Scotia after declaring his public trust in the King. He was a military medical practitioner in Nova Scotia between the years 1776 and 1778, during which time there was a large smallpox outbreak. Dr. Jeffries was able to save many children’s lives by performing inoculation.

(Wellcome Collection, V0011069)

During the late eighteenth and early nineteenth centuries smallpox was a major epidemic, especially among children. Smallpox was a disease that most loyalists would have known about from the American colonies and with Dr. Jeffries' practice of inoculation for children, they had a way to defend themselves from the virus. Although those who contracted smallpox and survived were usually immune, smallpox was one of the most feared diseases due to its high illness and mortality rates; it was infectious and caused fever along with eruptions or pustules that could lead to scarring or blindness. Because of the nature of smallpox and the severity of the outbreak in Nova Scotia during the 1770s, surgeons and physicians had to work around the clock to inoculate as many adults and children as possible. Dr. Jeffries’ own explanation of how he inoculated as follows in Allan Everett Marble’s book, Surgeons, Smallpox, and the Poor: A History of Medicine and Social Conditions in Nova Scotia, 1749-1799: "'[I] used a lancet moistened with the [smallpox] pus, and made two or three scratches with the infected lancet'", or "'[I] used a bit of [contaminated] thread laid on an incision.’” The purpose of the inoculation was to confer a milder form of the disease and subsequently prevent the patient from contracting natural smallpox. Dr. Jeffries worked at the general military hospital (which he also referred to as "the Garrison Hospital") in Halifax and the hospital on Georges Island to assist in smallpox inoculations which saved children's lives.

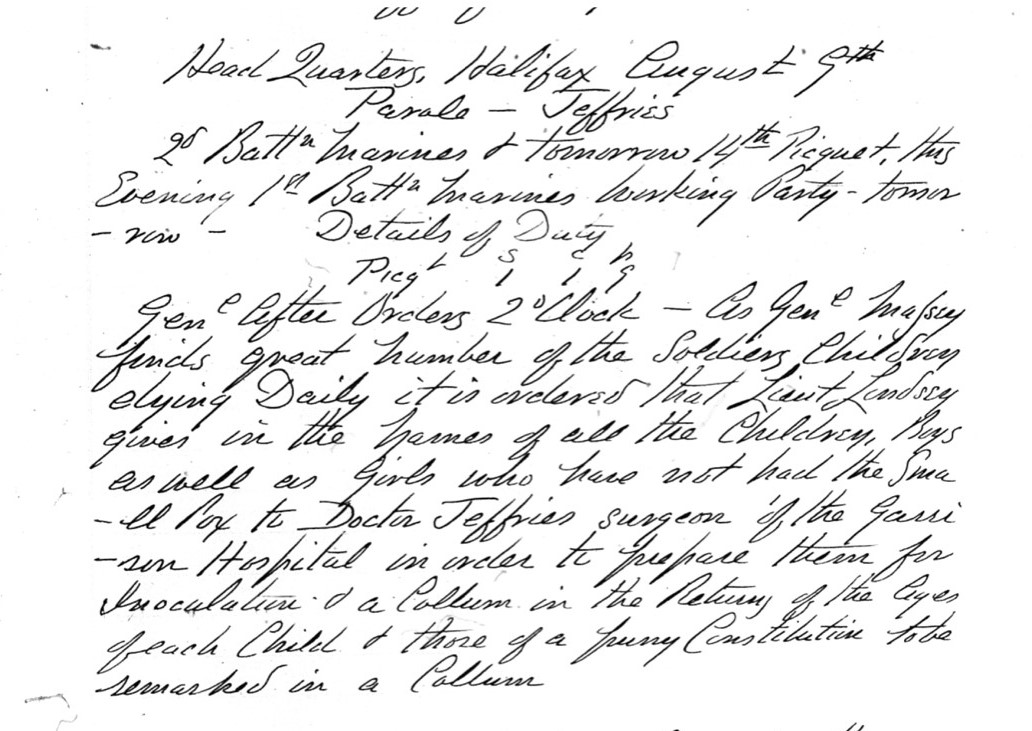

Dr. Jeffries’ Orderly Book, recorded while a surgeon at Halifax's general military hospital in 1776, shows that he was busy with soldiers’ wives and their children who came to be inoculated for smallpox. In Dr. Jeffries had the authority to elect a certain number of the soldiers’ wives to tend to the children who were inoculated and quarantined on Georges Island. This document shows the authority Jeffries had over the people who attended and worked at his hospital. It is clear in the Orderly Book that Dr. Jeffries was assertive when arranging and ordering staff and employees, demonstrating that he would have followed military protocols about hospital management and practice.

During the eighteenth century, Halifax’s medical practitioners meticulously tracked and documented smallpox death rates, which were high among adults but even higher for children. In his Orderly Book, Dr. Jeffries wrote about the inoculation of children he would be performing: “Head Quarters – Halifax August 9th [...] great number of the Soldiers Children dying Daily, it is ordered that Lieut. Lindsey gives in the names of all the Children, Boys as well as Girls who have not had the Smallpox to Doctor Jeffries surgeon of the Garrison Hospital in order to prepare them for Inoculation.”

The dangers of smallpox motivated some people to undergo inoculation in the hopes that it would protect them from acquiring the more severe form of the disease naturally. While parents were not always completely assured of the safety surrounding the practice of inoculation, Dr. James Jurin, who was secretary to the Royal Society and a London-based physician, had written in the 1720s: “’People do not easily come into a practice in which they apprehend any hazard unless they are frightened into it by a greater hazard.’” In eastern England, the Reverend Robert Houlton preached to skeptical parents in 1766 and was later quoted in Ulrich Tröhler’s work, "'If you neglect to have your children inoculated, and they are infected, as they grow up, with the natural small-pox and die, have you not real cause to be uneasy, and to accuse yourselves of carelessness and want of natural affection, as the means to have saved their lives.’”

Smallpox was an epidemic virus that spread rapidly among children and accounted for the most common reason for premature death in infants. It was a disease that was highly contagious but could be subsequently prevented or mitigated with the use of inoculation. Although eighteenth-century faced the same decision of whether to inoculate their children as modern parents, it was a relatively new and frightening procedure for many at the time. However, with Dr. Jeffries’ service, many children in loyalist Nova Scotia were successfully inoculated and avoided the potentially more dangerous the effects of contracting natural smallpox.

Secondary Sources

John Compton and Michael Pfau, “Spreading Inoculation: Inoculation, Resistance to Influence, and Word-of-Mouth Communication,” Communication Theory, (Dartmouth: Wiley Online Library, 2009)

Allan Everett Marble, Surgeons, Smallpox, and the Poor: a History of Medicine and Social Conditions in Nova Scotia, 1749-1799, (Canada: McGill-Queen’s University Press, 1993)

Ulrich Tröhler, “To Assess and Improve: Practitioners’ Approaches to Doubts Linked with Medical Innovations1720-1920,” in Thomas Schlich and Ulrich Tröhler, eds., The Risks of Medical Innovation: Risk Perception and Assessment in Historical Context, (New York: Routledge, 2006)

Alan D. Watson, "Combating Contagion: Smallpox and the Protection of Public Health in North Carolina, 1750 to 1825,” North Carolina Historical Review 90, no. 1, (January 2013)

Stanley Williamson, The Vaccination Controversy: The Rise, Reign and Fall of Compulsory Vaccination for Smallpox, (Liverpool: Liverpool University Press, 2007)

Victoria Ackerman is a fourth year English student at the University of New Brunswick.

![]()

Add new comment