- Submitted on

- 5 comments

It is terribly easy for scholars to ‘miss the forest for the trees.’ About a month ago, I emerged from my den of research to give a biographical presentation about Christopher Sauer III. At the end of my talk, I was caught off guard by an obvious, down-to-earth question. “Why,” my sensible classmate asked me, “was a German so loyal to the British cause in the American Revolution?”

I was flummoxed. In the midst of my detailed research about Sauer’s Loyalist activity, it had not occurred to me to question how his German heritage and British political sentiment fit together. What was the link between an 18th century German printer and Britain?

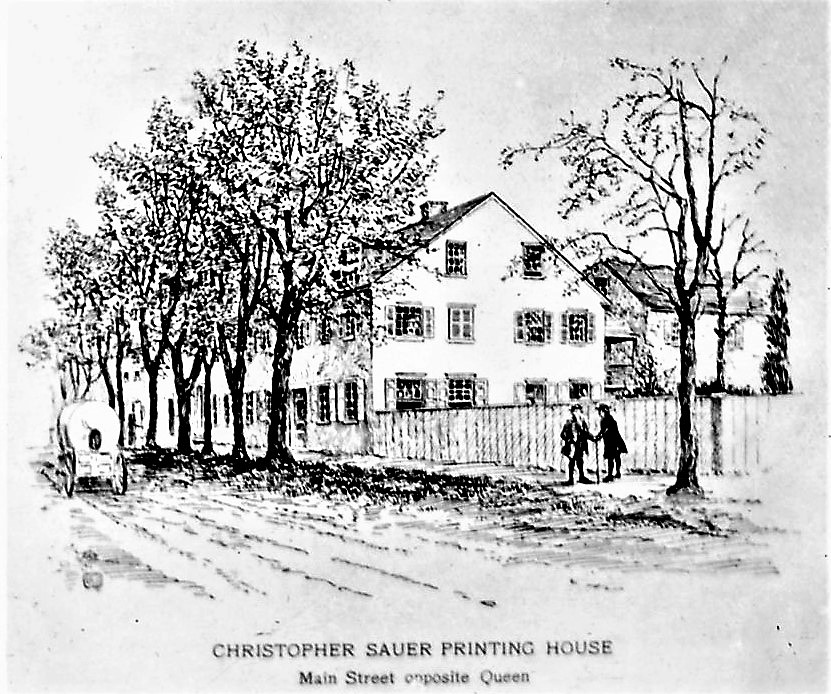

(Image courtesy of the Germantown Historical Society/ Historic Germantown2013.5.4.48b)

Christopher Sauer (also “Sower” or “Saur”) III was undoubtedly German. True, he was a third-generation immigrant to America (preceded by Christopher Sauer I and II), but half a century in Pennsylvania had done nothing to weaken the family’s national heritage. The Sauers were the editors of a highly successful printing press in Germantown which published the weekly newspaper, Die Germantowner Zeitung. Moreover, Christopher II and III both belonged to a German radical sect called the Brethren, or the Dunkards/Dunkers (so called because of their belief in immersion baptism). It was the type of religious organization which maintained a distinct community and discouraged its members’ involvement in secular affairs. When Christopher Sauer III set up shop in New Brunswick after the revolution, he was known – and disliked – for keeping his distance from the rest of society. In 1790 Sauer established an estate twelve miles outside the city of Saint John, New Brunswick, which enabled him to print about the same city without having to interact too much with its inhabitants. This sense of unbelonging eventually caused him to close shop in 1799. He returned to his German community in the United States, where he died suddenly from a stroke.

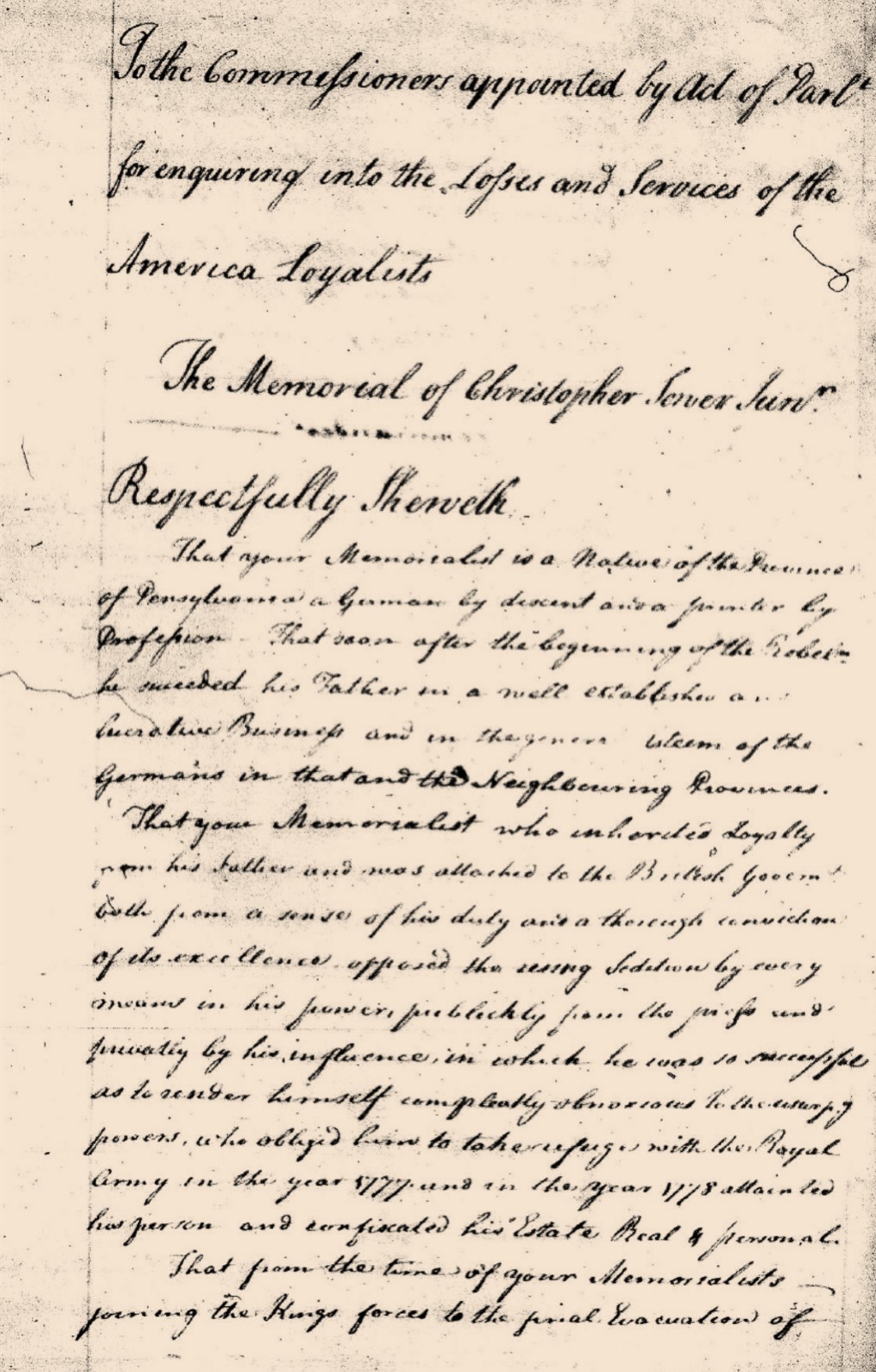

Yet, despite his unquestionable German-ness, Sauer was a self-proclaimed Loyalist. His statement before the Loyalist Claims Commission, the British committee in charge of compensating Loyalists for their wartime losses, bears evidence to this effect. Sauer declares:

“That your Memorialist…was attached to the British Government both from a sense of his duty and a thorough conviction of its excellence opposed the rising Sedition by every means in his power…”

(Great Britain Audit Office. Claims, American Loyalists: Series I (AO12): 1783-1788, AO 12/38/291, The Loyalist Collection, microfilm reel 11, original The National Archives)

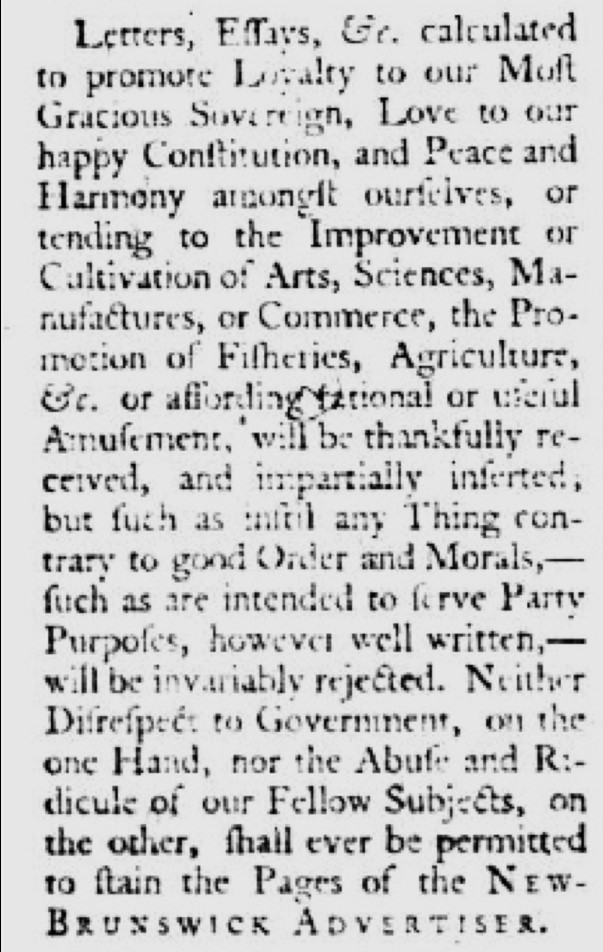

What were the “means” by which Sauer opposed the “rising Sedition”? His print-work is the most obvious. In 1776, a patriot committee tried to censor loyalist sentiment by forbidding Sauer to print “any political paper whatsoever.” A 1778 edition of his newspaper declared that America was sick and could only be cured by “pills” made of bullets. In 1780, Sauer published a rebuttal to Thomas Paine’s pro-patriot tract, Common Sense. Even his post-revolutionary newspaper was unmistakably loyalist; it featured only material “calculated to promote Loyalty to our Most Gracious Sovereign.”

(Microform Newspapers, Archives & Special Collections, UNB Libraries, reel 1)

His Tory rhetoric was grounded in concrete actions. Sauer gathered information for three British commanders. For a time, he accompanied the British forces in Pennsylvania and was captured by American troops who injured him, stole his horse, and imprisoned him for five weeks. Most significantly, Sauer was part of the Associated Loyalists of Pennsylvania and Maryland movement, which helped to organize loyalist resistance within patriot territory.

Sauer was thus unmistakably German and unashamedly loyalist. What united these elements into a cohesive person?

My first clue came from Sauer’s file with the Loyalist Claims Commission. There, he explains that he “was one of a Religious German Society called Dunkards who Excommunicated those who opposed the British Government.”

It was a clue – but a puzzling one. Why did the radical pietist sect of Dunkers support the British government? The relationship seems incongruous, for the Brethren sect were pacifists. In fact, Christopher Sauer II had balked even at paying taxes directed towards military ends. How could his son, Christopher Sauer III, invoke this pacifist pietist sect as a cause for supporting the warring Anglican nation?

Both Dunker belief and loyalist policies opposed revolution in principle. The first American Brethren had lived through the Thirty Years War in the German Palatinate. They knew the horror of civil war, and, like the loyalists, rejected it as a means for achieving social change.

Dunkers were also linked to Britain by a historical debt; when they had fled religious persecution in Europe, it was the British colony of America that had welcomed them.

And yet – why was the link so strong? Why were Dunkers threatened with excommunication unless they supported the British cause? Why did Sauer endure imprisonment and exile for his loyalist stance?

The key was the radical sect’s understanding of temporal authority. Brethren believed that the British monarch was the proper authority established by God. Accordingly, they were required to obey the divinely willed ruler. The 1779 Yearly Meeting of the Brethren declared:

“Inasmuch as it is the Lord our God who established kings and removes kings, and ordains rulers according to his own good pleasure, and we can not know whether God has rejected the king and chosen the [American] state, while the king had the government; therefore we could not, with a good conscience, repudiate the king and give allegiance to the state.” (Quoted in Durnbaugh, 149)

While the British monarch remained in power, the German Dunkers had no evidence that God was displeased with him. Quite the contrary – the only logical deduction was that his reign was divinely willed. They were therefore duty-bound to support his rule. Christopher Sauer’s Loyalism, far from being inconsistent with his heritage, was in fact firmly linked to the radical German sect and its understanding of temporal power.

I hope this, at last, answers my colleague’s excellent question. And I hope that this project will remind me not to become so bogged down by details that I ‘miss the forest for the trees.’

Yet, at the same time, Sauer reminds us not to ‘miss the trees for the forest.’ It is terribly easy for us to become so fixated on a general model that we overlook the details. A Radical German Pietist, perhaps, does not correspond to our pre-conceived model of a “Loyalist.” Sauer’s story encourages us to venture further into the realms of loyalist research - for there are many kinds of trees in a forest, and who knows what we shall find?

Ruth Savidge is a History (Honours) student at the University of New Brunswick.

Recommended Sources

D. G. Bell, Early Loyalist Saint John: The Origin of New Brunswick Politics 1783-1786 (Fredericton, NB: New Ireland Press, 1983).

Davies, Gwendolyn Davies, “New Brunswick Loyalist Printers in the Post-War Atlantic World: Cultural Transfer and Cultural Challenges.” In The Loyal Atlantic: Remaking the British Atlantic in the Revolutionary Era, Jerry Bannister and Liam Riordan eds. (Toronto: University of Toronto Press, 2012).

Donald F. Durnbaugh, Fruit of the Vine: A History of the Brethren 1708-1995 (Elgin, Illinois: Brethren Press, 1997).

Russel J. Harper, “Sower (Sauer, Saur) Christopher,” Dictionary of Canadian Biography, vol. 4 (University of Toronto/Université of Laval, 2003).

James O. Knauss, “Christopher Saur the Third,” The Proceedings of the American Antiquarian Society (Worcester, MA: American Antiquarian Society, 1931).

Marie Tremaine and Patricia Fleming, A Bibliography of Canadian Imprints 1751-1800 (Toronto, Ontario: University of Toronto Press, 1999).

Comments Add comment

So, was there no connection

House of Hannover connection

Thanks for your comment. You raise a great point; the potential connection between German loyalism and the House of Hannover would certainly be interesting to research further. I did not pursue that line here, since Sauer's records pointed to his religious convictions as the primary reason for his loyalist stance. But I would not rule out the possibility that other German immigrants were drawn to the loyalist side by King George III's German roots. - Ruth Savidge

German Connection

Sauer as courier for Pennsylvania Loyalists

Sauer comment

Thanks very much for this interesting anecdote about Christopher Sower III! You can find a full interactive biography of his life on New Brunswick Loyalist Journeys.

Add new comment Comments