- Submitted on

- 6 comments

For the next three weeks, we are very pleased to feature series of posts authored by undergraduate students from Dr. Wendy Churchill's University of New Brunswick History course, "Medicine and Society in the Early Modern British World" using Loyalist Collection resources.

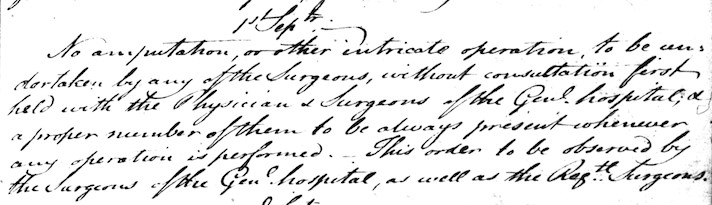

On the 1st of September 1775, the War Office of Great Britain issued an order to regimental and general surgeons stating that no amputations or other intricate operations were to be performed without first consulting the Physicians and Surgeons of the General Hospital. Issued to surgeons in the British Military during the American Rebellion, one would think that surgeries might be crucially important to ensuring the survival of soldiers wounded in combat, so it begs wonder why they would be prohibited from performing potentially life-saving actions. The hierarchical nature of medical practice in Britain carried over to the military, resulting in prejudicial orders such as the one examined here.

“No amputation, or other intricate operation, to be undertaken by any of the Surgeons, without consultation first held with the Physicians & Surgeons of the Genl. hospital; & a proper number of them to be always present whenever any operation is performed. This order to be observed by the Surgeons of the Genl. Hospital, as well as the [Regimental] Surgeons.”

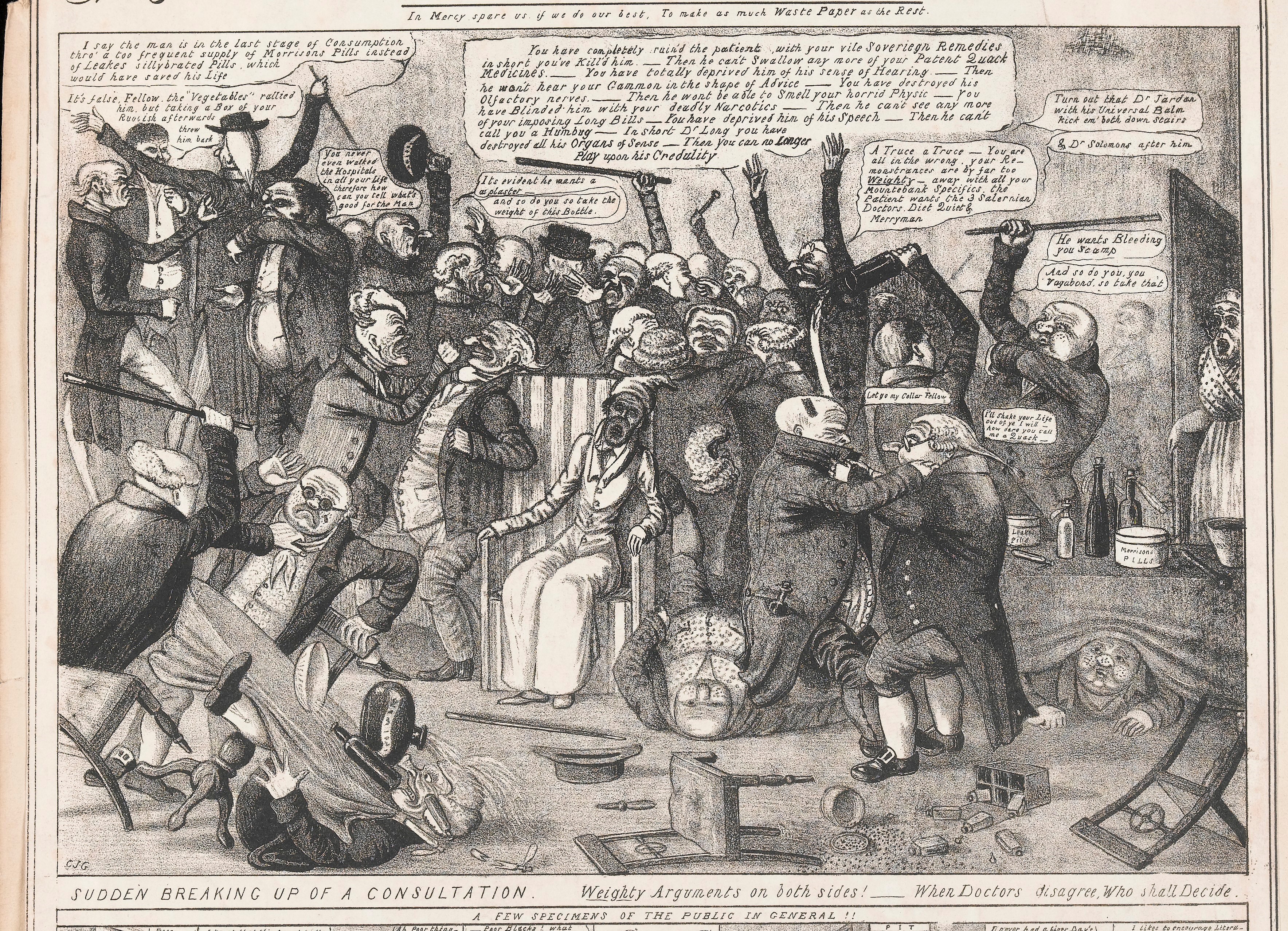

The hierarchical structure of licensed practitioners in early modern England and the competition and animosity between these “regulars” (licensed, educated practitioners) and the “irregulars” (untrained practitioners) created a great deal of tension. At the top were the licensed physicians, tasked with diagnosing illness and prescribing treatment. These men were university-educated and licensed under a guild or college of physicians. They belonged to institutions, such as the London College of Physicians, which dominated medical practices and sought to subordinate irregulars. Physicians saw themselves as above other practitioners, as it was under their guidance that patients then went to visit the two underling professions. Surgeons, who achieved their position by means of a seven-year apprenticeship, dealt with external injuries, setting bones, purging, and internal surgery. This last, however, was extremely risky and painful during the early modern period, so it was much less common. Many surgeons began as barbers, as both professions required knife skills. Parallel in status with surgeons were the apothecaries, who mixed remedies as prescribed by the physician. As with the surgeon, apothecaries learned their trade through apprenticeship. Many apothecaries attempted to subvert physicians by prescribing medicine themselves, leading to great tension between the two lines of work.

Irregulars were on their own, lower branch of the tree (which physicians probably would have preferred to have cut off). There is a long list of people who practiced medicine without formal training or licensing, consisting of empirics, herbalists, and wise women among many others. Empirics provided the same services as physicians, but acquired their knowledge through apprenticeship at most. These informally trained and less knowledgeable individuals (according to regular practitioners) offered essential medical assistance at a fraction of the cost, but at the risk of lower quality treatment. For some, however, they were the only option.

The military medical services were arranged very similarly to medical practice in Britain and divided into the general and regimental hospitals. All decisions in the medical services were controlled from the top. The director of the hospital and the commander-in-chief dealt directly with the War Office, expressing issues and enforcing orders. High-ranking officers, such as colonels, were typically the ones who selected medical staff, though the task was meant for the surgeon-general and physician-general, the head of their respective professions at each hospital. Below these high-ranking positions was a picture very similar to that of the medical hierarchy in Great Britain. Physicians were at the top. Those in military service were typically licensed and began in general hospitals, the more permanent hospitals kept well away from battle. Surgeons followed, most often starting out as regimental surgeons and having to work their way up to hospital surgeon. Employment as a surgeon, however, could be purchased, meaning many unweathered surgeons were able to become hospital surgeons. Apothecaries were slightly below surgeons, tasked with maintaining the medical supplies and providing prescriptions. At the bottom were the mates, often inexperienced, who did as they were commanded by their superiors.

There were serious distinctions between regimental medical staff and hospital medical staff. In terms of capability, status, and wage, regimental staff (those who traveled with military regiments) were below their hospital counterparts. High-ranking officers considered the regimental surgeons and mates as limited in ability in comparison with the lauded hospital staff, though it was the officers who hired them after they passed extremely simple exams that did not sufficiently test their abilities.

Regimental mates typically served to assist the surgeon, but in times when his superior was not available for whatever reason, the full duties fell upon the mate. While serving as a mate did propel many into becoming surgeons, unskilled hands were not desirable for any sort of serious operation. Fortunately for the wounded, this was rare and any difficult operation was handled by the regimental surgeon or the soldier was sent to the general hospital. Due to inadequate restrictions and lack of support, it is no wonder regimental medical services had a bad name when compared with the general hospitals.

In effect, the order from the War Office barred regimental surgeons from performing any serious operations, and to do so, consultation must be held with hospital staff. As regiments were away from the hospital, it was not possible for the doctor to meet with his superiors. This order from the War Office sought to discredit regimental surgeons and prevent these supposedly unskilled men from causing any harm.

The “medical marketplace” during the early modern period was headed by the physicians, who sought to place themselves on a pedestal above the learned surgeons and apothecaries. These regular practitioners were university-educated and formally trained. The War Office and various guilds and colleges acted as the overarching groups that set the doctrine and inhibited the “lesser” practitioners. The irregulars were discredited at every opportunity due to their supposedly insufficient education and training. The military medical services at the time of the American Revolutionary War contained a very similar model, with general hospital staff being analagous to the regulars and regimental staff akin to the irregulars. Prejudices persisted, lowering the status and opportunity for the regimental staff and seeking to separate the hospital staff from their counterparts to preserve their hierarchical views.

Secondary Sources

Paul E. Kopperman, “Medical Services in the British Army, 1742–1783,” Journal of the History of Medicine and Allied Sciences 24, no. 4 (1979): 428-455 and “The British Army in North America and the West Indies, 1755-83: A Medical Perspective,” in British Military and Naval Medicine, 1600-1830, Geoffrey L. Hudson, editor, (New York: BRILL, 2007).

Roy Porter, Disease, Medicine, and Society in England, 1550-1860, (New York: Cambridge University Press, 1995).

Andrew Wear, “Setting the Scene” in Knowledge and Practice in English Medicine, 1550-1680, (New York: Cambridge University Press, 2000).

Colin Powell is currently an Arts student at the University of New Brunswick and holds a BA in History from St. Francis Xavier University.

![]()

Comments Add comment

Genealogy

British Army surgeons

Hi! Thank you for your comment. Our specialty is in loyalists of the American Revolution and British Army members who fought in that conflict, so we would suggest contacting The National Archives (UK) and using their website as starting point for your research: https://www.nationalarchives.gov.uk/ Good luck in you research journey!

Social/class status of 18th century physicians in British Army?

Social status of physicians

Thank you for your interest in our blog! We would recommend you check the the work of Dr. Wendy Churchill for more on social class of physcians in this period. This post was written by one of her students.

Thank you

Regimental surgeons and surgeons mates in the Hessian Regiments

Add new comment Comments