- Submitted on

- 0 comments

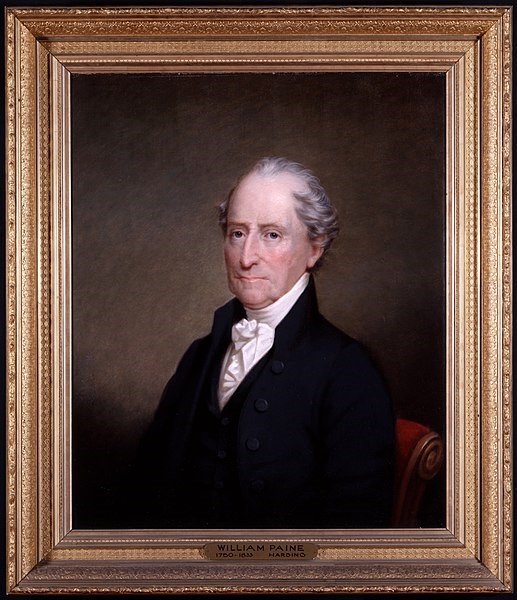

Throughout the eighteenth century smallpox was sweeping the Americas and Europe, and in an attempt to reduce the number of deaths, physicians were practicing inoculation on those who were not ill in order to keep them from becoming sick with smallpox, much like today, when we receive vaccinations in order to avoid sickness. In 1772 while studying medicine in Worcester, Massachusetts, William Paine wrote medical notes on how to perform inoculation and also how to care for patients in the days following inoculation, giving us a firsthand account of how physicians used this practice in the eighteenth century. Paine’s medical notes show us that inoculation was not just a quick process like vaccination today, but that patients who had been inoculated required constant care in the days after this procedure as well.

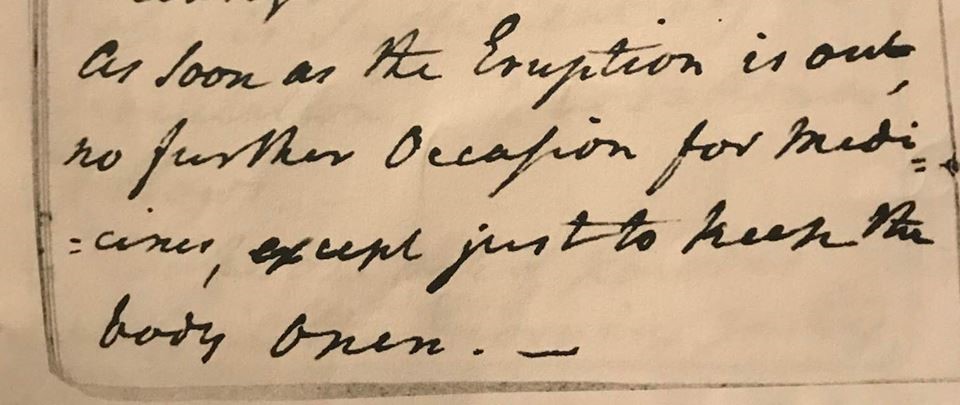

In his medical notes, Paine made it clear that inoculation was not a one-step procedure, and that while the process of inoculation itself was complicated, what was most detrimental to the health of a patient were the steps taken after the initial inoculation process, or what Paine referred to as “The Operation”. In order to inoculate a patient, a medical practitioner used a lancet to cut small pustules of smallpox from an already infected person, and then inserted them into the skin of the patient in order to allow their body to build immunity to the disease by giving a small introduction to the disease. What makes this document from Paine so valuable is that it describes the inoculation process, how to care for patients, along with what to expect the following days after inoculation. While this document is valuable to us today, it would have been equally as valuable at the time it was written due to its descriptive nature because other physicians could have used it as a medical reference. Paine’s medical notes were so descriptive that they even described care for patients as young as under one year of age to children five to seven years old, and also explained the typical treatment for an adult.

(Credit: Science Museum, London. CC, via Wellcome Images)

In contrast to medical doctors today, much of the medication that Paine prescribed consisted of natural elements, which it seems most people had access to, such as salts, a mix of ten grains, and flower of sulphur, which is a bright yellow powder that comes from volcanic brimstone deposits.

In addition to medicines that could be found in nature, many of the treatments that Paine describes are related to humoral theory. It was believed during this time that if one was sick, it was due to an imbalance in one of the four humours, blood, phlegm, yellow bile and black bile, and the only way to fix this imbalance was to find a way to expel the access humour in order to even them back out. This is why Paine often prescribed treatments that caused vomits or stools, such as “Black Pills”, purging powders, or “The Punch”, which induced vomiting or frequent stools in order to rid the body of whatever was causing the excess in the humours.

It was also a common belief during the eighteenth century that the constitution of the air or water in an area could interfere with one’s health. The belief that miasma, meaning unpleasant or unhealthy air, could cause sickness is why Paine also believed that the patient should be “exposed to open air” while doing some sort of exercise. Exercise was important because it was considered to be a form of cleanliness for the body, by sweating out excess humours from the body.

(William Paine, Papers: 1768 – 1835, The Loyalist Collection; original document held by the American Antiquarian Society)

While the practice of inoculation really became prevalent during the eighteenth century through to the mid- nineteenth century, the practice became less valued with the introduction of vaccination, which proved to be much more effective than inoculation. This involved infecting the patient with a benign case of cowpox which helped the patient build an immunity to the infection, while in contrast, in order to perform inoculation, the patient was intentionally infected with a less aggressive version of smallpox, and often caused the patient to become ill with some form of the disease before gaining immunity.

While William Paine’s medical notes are incredibly valuable to us and provide insight into the medical practices of his time, it is noteworthy that he was not officially licensed as a physician until 1782, ten years after these medical notes where taken. William Paine lived to see vaccination become widely practiced. However, his medical career faded out in favour of politics when he lived in New Brunswick after the American Revolution, focusing on academia and education, including petitioning for an “Academy or School of Liberal Arts and Sciences” (this would later become the University of New Brunswick) in 1785. Throughout his life William Paine was very active and has left us an important source that provides us with a clearer view into this period in history, through his language, prescriptions, and knowledge that has been preserved in his writings.

Somer Stewart is in her fourth year of her Bachelor of Arts degree at UNB, majoring in History.

This blog post was written as part of the UNB Department of History course, "Revolutionary and Loyalist Era Medicine" taught by Dr. Wendy Churchill.

Secondary Sources Used

Jacques, Bos, “The Rise and Decline of Character: Humoral Psychology in Ancient and Early Modern Medical Theory,” History of the Human Sciences 22, no. 3 (2009): 29-50.

Romola J. Davenport, Jeremy Boulton, and Leonard Schwarz, “Urban Inoculation—A Reply to Razzell”. The Economic History Review, 69, no. 1 (2016): 188-214.

Mary J. Dobson, Contours of Death and Disease in Early Modern England. Cambridge Studies in Population, Economy, and Society in Past Time, 29. (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1997).

Carol Anne Janzen, “PAINE, WILLIAM,” in Dictionary of Canadian Biography, vol. 6, (University of Toronto/Université Laval, 2003).

A. J. Mercer, “Smallpox and Epidemiological-Demographic Change in Europe: The Role of Vaccination.” Population Studies 39, no. 2 (1985): 287-307.

![]()

Add new comment