- Submitted on

- 0 comments

Siobhan M. Carlson is a master’s student at the University of New Brunswick in Interdisciplinary Studies. Her research focuses on the use of biomedical models in gothic and cult fiction. Siobhan has worked in libraries for three years—including the Harriet Irving Library on the University of New Brunswick, Fredericton campus. While at the Harriet Irving Library, she has worked in three department: Archives and Special Collections, Reference, and The Centre for Digital Scholarship. Presently, she works as a Research Assistant for Dr. Edith Snook, UNB English Department, and is on the editorial board of QWERTY. Her pastimes include camping, hiking, and tending to a precocious hedgehog name Anya.

As a researcher for Dr. Snook’s project on Early Modern Maritime Recipes, Siobhan has been digging deep into the vast Loyalist Collection for her research. I have asked her to share some of her experience working with the collection.

Annabelle: Please tell me about the research project you are working on.

Siobhan: I am currently working on Dr. Edith Snook's project entitled “Early Modern Maritime Recipes.” It is a SSHRC funded research project partnered, with collaborators at Dalhousie University. The objective of the project is to collect recipes from early modern history (pre 1800s) in the Maritimes. Eventually, the goal of the project will be to develop a database of recipes. There are similar databases around the world dedicated to the collection and dissemination of early modern recipe culture (see Wellcome Library).

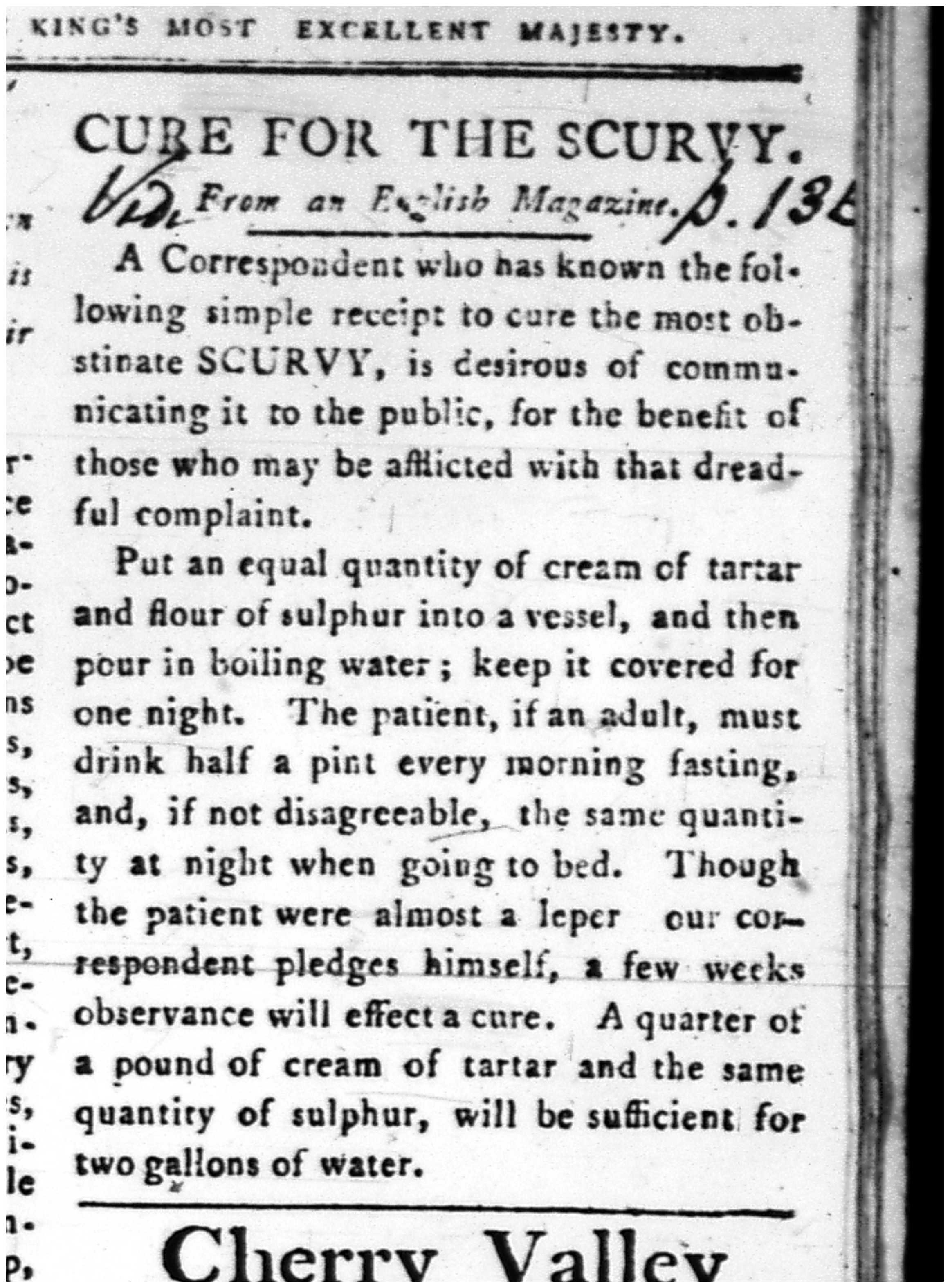

With this kind of project, it is important to remember that recipes were not only just for food but also had medical properties as well—sometimes because there was little to no differentiation between the two.

Annabelle: How did you get involved in this research project?

Siobhan: During my course work for my current degree, I took Dr. Snook's course on early modern women's writing. During this period, recipe books were a way for women to catalogue and share their domestic and medical knowledge. Recipe books were often passed down from the primary author to another woman in her family who would include her own entries and knowledge. Thus, there are recipe books that span several generations.

The course helped me to prepare to conduct this type of research—coupled with my work in archives and digital imaging. I was excited when I learned about this project.

Annabelle: What is your research methodology?

Siobhan: We are currently in the collection stage, which means, I spend most of my time looking for recipes in archival material. We are using a variety of sources, such as newspapers, personal papers, and diaries. The research is going well so far! It is a bit like looking for a series of needles in a haystack, but that's half the fun!

Annabelle: What challenges are you finding in using primary sources? How do you cope with these challenges?

Siobhan: One of the biggest challenges with working with sources from this period is that most of the documents that you examine are primary documents, and are, therefore, often written by hand. There are a variety of ways one can help to ease this process (for a more detailed explanation, please see this previous blog post). Above all, the best way to learn how to read handwriting better is to practice!

There are many factors that can also impact handwriting. For example, I am currently working on the papers of Edward Winslow. In one of his diary entries, he mentions that he has gout in his right wrist—making it difficult for him to write and even harder for us to read.

The most important lesson I have learned is that recipes are often where you least expect them. Sometimes they are scribbled into the margin of a diary or book, or casually mentioned in a letter.

Annabelle: What do you find most interesting about this research?

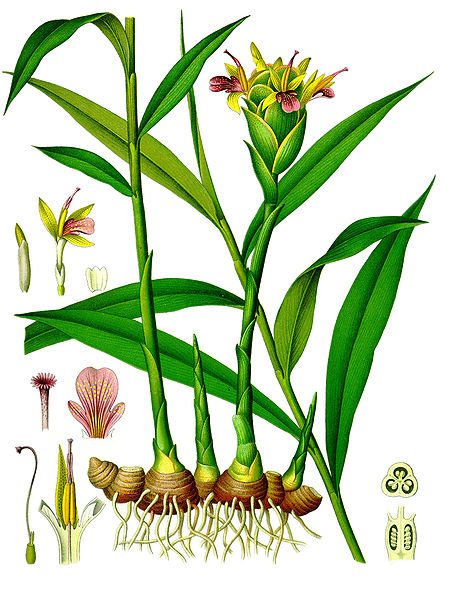

Siobhan: What I find interesting is how close some of the recipes are to our own home-remedies. For example, I have located a recipe that recommended ginger to someone with an upset stomach. This is something that is still used today. On a similar note, the use of ginger also indicates the extent to which goods were imported into the region, as ginger grows in warmer climates.

Annabelle: Have you found anything particularly interesting or amusing in your research?

Siobhan: I have enjoyed working on the recipe project so far. I think that the most amusing thing I located, so far, was a very detailed article on the best way to make manure, and subsequently, the best way to grow food. It was an article from a pre-1800 Prince Edward Island newspaper. In the same publication, there was also an article on the best way to grow potatoes from various types of cuttings.

Another common thing to find in diaries is descriptions of the weather! I know way more about the weather patterns in the 1780s than I expected.

Thank you, Siobhan for taking the time to speak to us about your fascinating research experience.

Annabelle Babineau is a student assistant at the Harriet Irving Library. She is currently completing her Bachelor of Arts in the English Honours Programme.

Add new comment