- Submitted on

- 2 comments

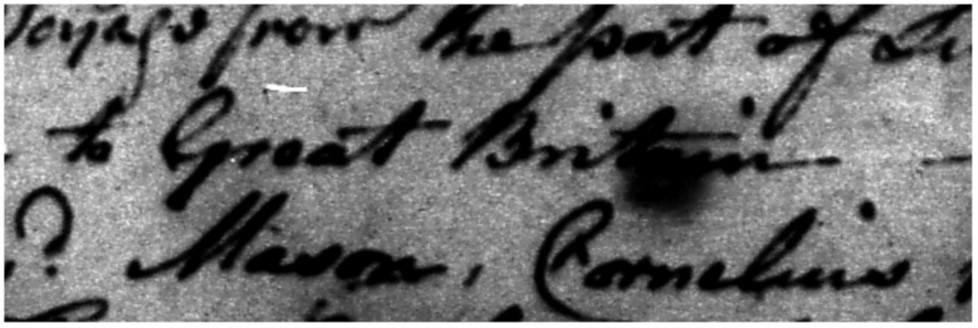

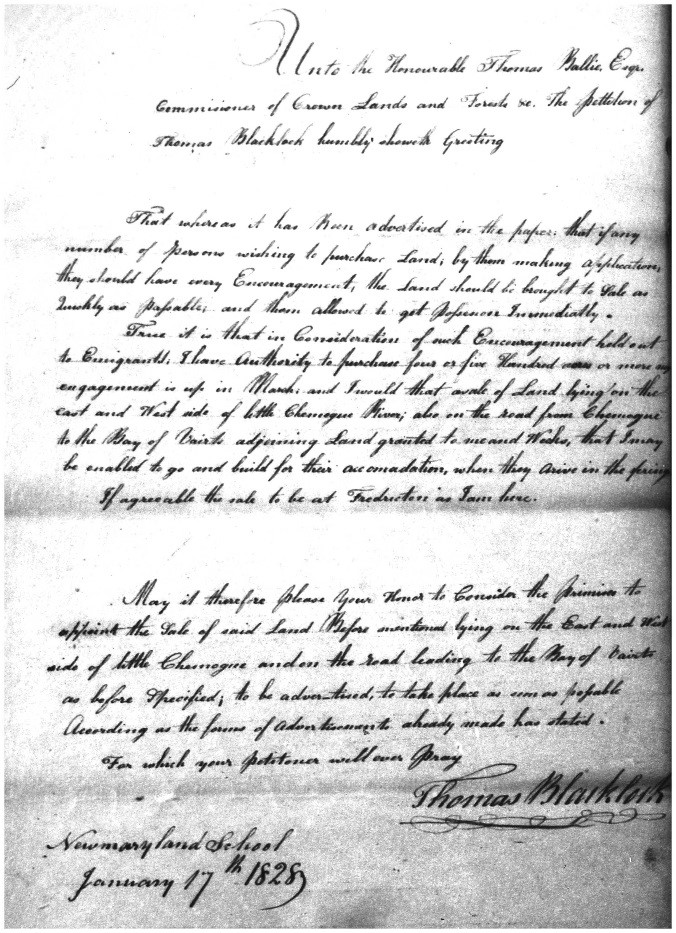

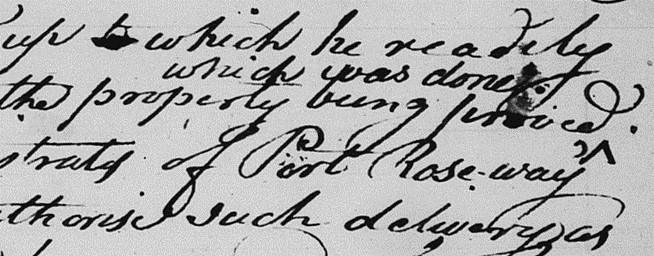

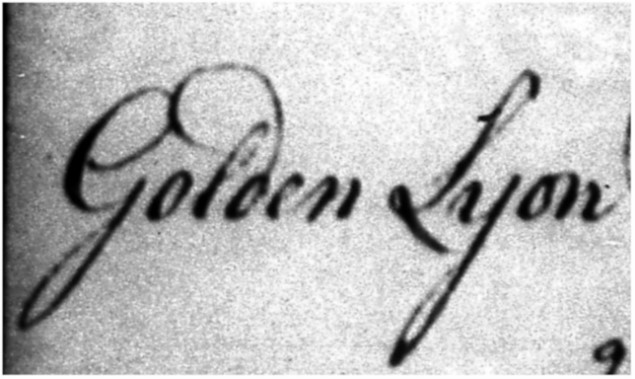

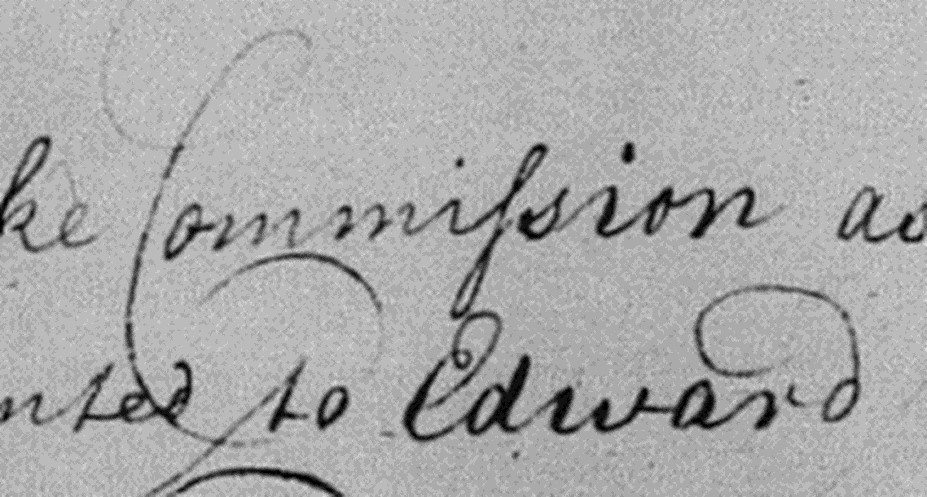

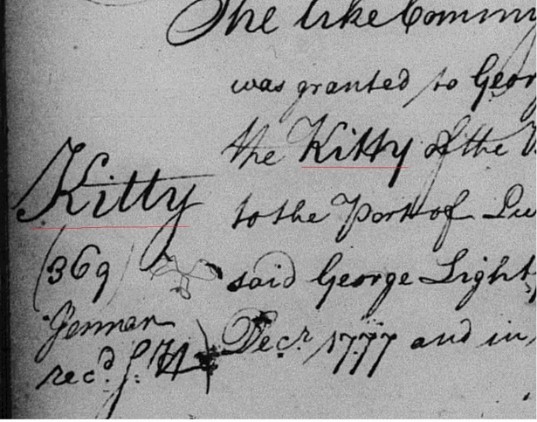

Researchers encounter an amazing variety of script (or sometimes more like scratch!) amongst the handwritten documents produced in the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries. To become adept at interpreting historical cursive writing, readers must develop particular skills over time. The art of reading and analyzing historic handwriting and manuscripts is called palaeography. As instruction in cursive writing has become greatly diminished as part of school curriculums, help in reading historical documents is becoming increasingly important to make sure researchers are still able to use primary sources such as those housed in The Loyalist Collection.

To help start the process of interpreting and transcribing a particular document, consider a few key questions:

What materials were used in the document’s creation?

Writing materials dictate the form writing takes; this comprises various surfaces for writing such as parchment, vellum, hand-made paper, and mass-produced paper. Writing utensils also shaped the form of writing and documents: lead (graphite) pencils, homemade and manufactured quills and ink, metal pen nibs (produced starting in the second half of the eighteenth century), or fountain pens (in use starting in the 1830s). Issues that may be encountered when dealing with original historical documents include ink blotches, fading, discoloured paper (foxing), tears and missing pieces, wrinkles and folds, and bleeding.

Why was the document created?

Grades and types of writing were associated with the purpose of the text and these types of styles are called hands. In describing hands, the aspect is the overall appearance of the script and the ductus is the speed at which the writing was done, number of strokes, and formation of letters. Round and copperplate were the most common hands for the period surrounding the American Revolution in North America.

Who created this document?

If you are unclear on who wrote a document or want to know more about the writer’s life, you may be able to draw out hints through palaeography. Like today, each writer has their own individual style and habits. Background reading in the subject area of the document will be of great help in both discovering the purpose, writer, and content of a document.

Where and when was it created?

The location and time of the writing of a document is useful information if available, but analysis of the writing itself can give clues to its own creation as writing changes over time and place. Some particular quirks found frequently in eighteenth and nineteenth century documents from the Atlantic world include variations in punctuation from modern usage, as punctuation was only standardized through printing. Phonetic (words written as they sound) and archaic (not in modern use) spellings were common—remember that not everyone was fully literate and many spellings were not standardized. Doubling or singling of consonants from modern spellings also occurred, and upper case letters could be used for nouns in the middle of sentences.

Much can be gained from reading documents in their original form—emotion, circumstances surrounding creation of document, materials used, later additions and notations, edited content, and details of the document’s purpose may be gleaned, making the extra effort worthwhile. The following list will help those beginning in palaeography, or indeed may also aid the veteran transcriber.

TIPS FOR DEALING WITH HISTORICAL WRITING:

- Try to identify words first, then attempt to understand content

- Start transcribing by writing down the words you know and leaving blanks

- Put guesses in brackets

- Match identifiable letters and words to unknown letters and words

- Write out an alphabet of how letters are formed in the document

- Go letter by letter if needed

- Look up unfamiliar words

- Count writing strokes (termed minims)

- Use a magnifying glass to follow writing strokes

- Read and reread to get syntax

- Use internal evidence (dates, places, events)

- Research people, places, etc. in secondary sources

- Cross reference with another document

- Look up individuals, events, etc. in other contemporary documents

- Read aloud if you need to!

- Leave document and return to it later

- As you develop confidence, go with your “gut”

- Ask someone else to look at it with a fresh eye

Note: All writing samples featured in this post are drawn from The Loyalist Collection.

Leah Grandy holds a PhD in History and works as a Microforms Assistant at the Harriet Irving Library.

Comments Add comment

Thank you for this very

Agreed, thanks for taking the

Add new comment Comments