- Submitted on

- 4 comments

From where we left off with Zimri Armstrong, a Black Loyalist who fought for the British, after the war he had indentured himself for two years to Samuel Jarvis in hopes of gaining the freedom of his wife and family; however, Jarvis abruptly left Saint John to return to Stamford, Connecticut. Having received no provisions, “being almost naked,” once the two years were up, Armstrong appealed to a Mr. Leonard only to learn that Jarvis sold his wife and family to a new master.

Armstrong, in desperation, appealed to a Mr. Knox, who went to Captain Whitmore. Despite the fact that other Loyalists, especially those that fought for Britain, would have received land and the resources needed to survive in British North America, all Whitmore could offer Armstrong was a bit of meat and flour since Armstrong could not present Whitmore with documents proving that he was indeed a freed man.

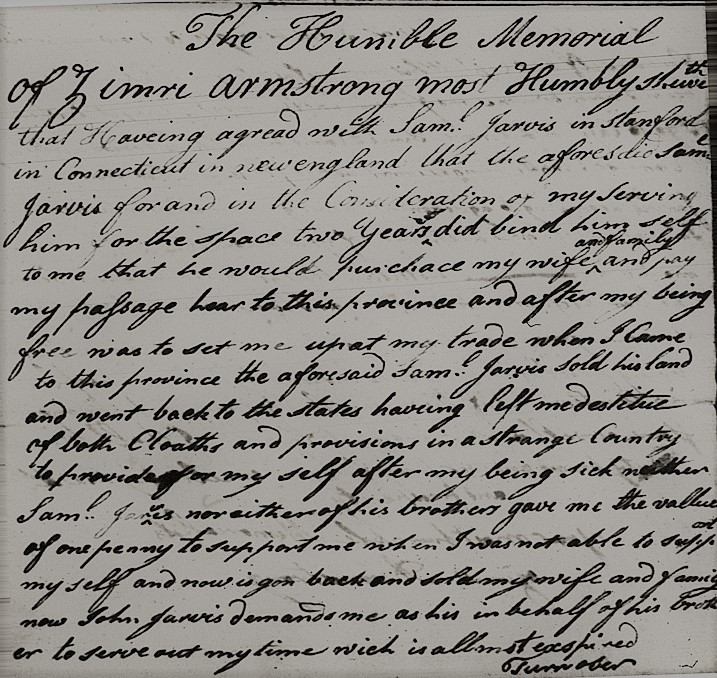

Armstrong’s next move was to petition to Thomas Carleton, the governor general and commander in chief of New Brunswick, which was received June 20th, 1785. Armstrong recounted his own miserable tale of betrayal in his petition, claiming that he “can produce the paper about [the] agreement between [himself] and Samuel Jarvis” and finally, graciously asking for “any land to grant [him] some . . . as other indigent loyalist.” Here, Armstrong is claiming his status as a Loyalist and most importantly, that he receive equal treatment; however, nothing amounted from Armstrong’s petition. Armstrong’s case was just one record of promises and orders that were never fulfilled. Another noteworthy example of discrimination is the Commander-in-Chief, Sir Guy Carleton order that the Black Pioneers – a regiment formed out of Lord Dunmore’s disbanded Loyalist unit, the Ethiopian Regiment – who embarked for British North America were to receive town lots, or if they were to become farmers, to receive 100 acres of land in the country, the same provision as any white Loyalist. This order was never fulfilled.

The last known possible record of Armstrong was from a newspaper published every Friday evening, The Gleaner, of Wilkes-Barre, Pennsylvania. On June 11th, 1813, the newspaper reports that “Zimri ARMSTRONG, a black man, drowned on Sunday last, in this town.” Armstrong presumably drowned attempting to cross a body of water in his travels back to his enslaved family; thus, one assumes that Armstrong never reunited with his wife and children.

Although Loyalists experienced great losses and hardships, none of the Jarvis’s experienced the betrayal that Armstrong experienced.

Key Sources

Ann Gorman Condon, “LEONARD, GEORGE,” in Dictionary of Canadian Biography, vol. 6, University of Toronto/Université Laval, 2003.

Harriet Jarvis Dobson Memorial, Burial: Saint John’s and Saint Andrew’s Episcopal Cemetery, Stamford, Fairfield County, Connecticut, USA. Find a Grave.

Memorial of Samuel Jarvis of New York in Claims and Memorials. The On-line Institute for Advanced Loyalist Studies.

Petition on behalf of Zimri Armstrong, 21 June 1785, Fredericton, "Black Loyalists in New Brunswick, 1783-1854," Atlantic Canada Virtual Archives, diplomatic rendition, document no. Armstrong_Zimri_1785_01. RS 108: Index to Land Petitions: Original Series, 1783-1918, Provincial Archives of New Brunswick, Fredericton, New Brunswick.

“1813 Gleaner.” Wyoming County Historical Society.

Isabelle Goguen is a student researcher for the Microforms Unit at the Harriet Irving Library. She is a graduate of UNBSJ with a Bachelor of Arts degree in English and History with a minor in Psychology.

Comments Add comment

Zimri Armstrong

The fate of Zimri Armstrong

Thank for you this additional information! Perhaps one of the "Zimri Armstrongs" in the two documents was a son or other relative. He is definitely a figure worthy of more study.

Zimri Armstrong

citation for New Brunswick's Zimri Armstrong in Sierra Leone

Add new comment Comments