- Submitted on

- 0 comments

Exactly when Gillam Butler acquired his estate on Campobello Island is uncertain, but there are clues that suggest he was never a destitute loyalist refugee, but rather an opportunistic New Englander who saw the border and a major financial opportunity. Following Sheriff Wyer’s first notice of auction of Butler’s Campobello property in the Royal Gazette, David Owen published his concerns in the Saint John Gazette as to the legality of Wyer’s position to auction off Butler’s seized estates on Campobello. David Owen was the nephew of British naval officer, William Owen, whose service in the Seven Years’ War awarded him title of Passamaquoddy Outer Island in 1767, later renamed Campobello. Three of Captain Owen’s nephews (including David) were listed as grantees because the total acreage of Campobello (about 10,000 acres) exceeded the amount normally awarded to an officer at the rank of captain. According to L. K. Ingersoll’s entry on William Owen in the Dictionary of Canadian Biography, Owen embarked from Liverpool, England in 1770 “with 38 indentured servants of all trades who were intended to form the nucleus of the new settlement.” Given Butler’s intention to embark for England, as opposed to the United States, at the height of his evading of officials in New Brunswick, it seems possible that Butler was once one of Owen’s indentured settlers: returning to a familiar place, with friends and relatives that he could fall back on, this hypothesis fits well with much of the scholarship on social networks in the eighteenth century.

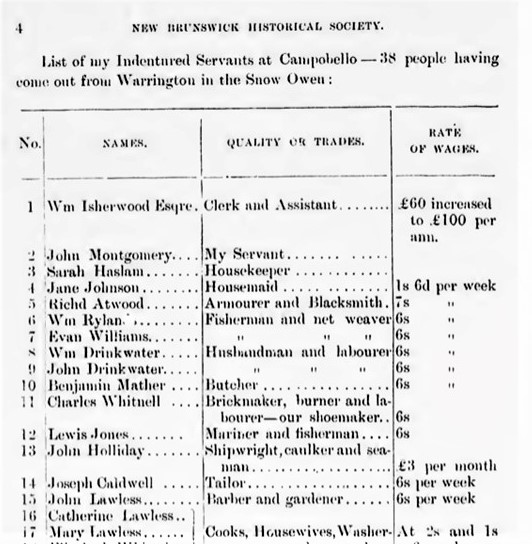

Thankfully, part of Captain Owen’s journal recounting his attempt at settling Campobello survives. The record, edited by William Francis Ganong of the New Brunswick Historical Society in 1897, depicts Captain Owen’s first days on the island in 1770, his heavy reliance on the Passamaquoddy First Nation for food and guides, and gives a list of his indentured settlers and their trades. Gillam Butler not among them.

Captain Owen resided on Campobello for less than a year, and his journal denotes the serious tensions between New England fishermen and merchants and the region’s Indigenous peoples. Owen quit the colony after a harsh winter, and it is unclear what happened to all the indentured settlers after 1771. Twenty-seven departed for England but were lost at sea, others emigrated to Boston (including the maternal grandmother of William Lloyd Garrison, the American abolitionist). Captain Owen continued his proprietorship over the island, advertising land for the potential settlement of a dozen farmers before his death in 1778 in Madras, India. What came of that venture remains unclear.

How Gillam Butler managed to claim ownership of the 2500 acres on Campobello that Wyer attempted to auction in 1787 can be answered only in pieces. The first clue can be found in Butler’s 1785 letter to Ward Chipman. Annoyed by the favoured position that Scottish merchants, like his rival William Pagan who later testified against him, were being given in St. Andrews by New Brunswick officials, Butler boasted to the Attorney General that he owned “the most valuable landed property in this Country… [and] I have kept from forty to Sixty people constantly employed.” If this boast were true, his interests should have superseded those of the Scottish merchants that laboured against him in county governance. What is key is that Butler was arguing in favour of his “American” interests, suggesting that he was in fact not British-born, as were the Pagans. As Ann Condon notes in her study, The Envy of the American States, Charlotte and Northumberland counties were unique in terms of the social makeup of governing groups: in most places in New Brunswick, American-born loyalist refugees chose representatives from their own lot, but Charlotte and Northumberland counties chose British-born representatives, making them the exceptions that proved the rule.

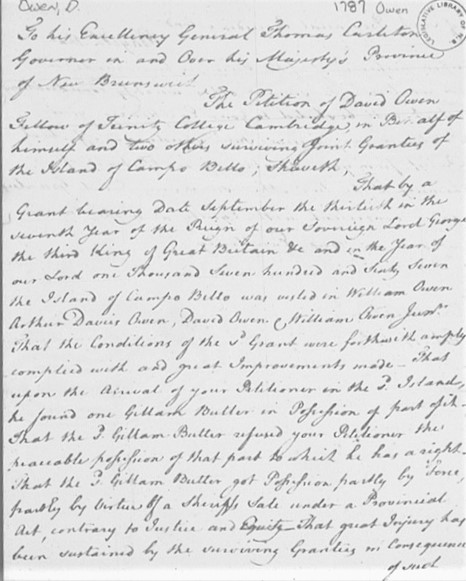

The second clue to Butler’s proprietorship, and how he acquired his estate on Campobello, is found in the petition of David Owen to the New Brunswick Land Grant Council in 1787. Owen returned to Campobello from Wales in the summer of that year, intent on recovering control of the island after his uncle died in Madras. When Owen caught wind of Sheriff Wyer’s intent to sell Butler’s estate, which accounted for nearly a third of the island’s landmass, Owen petitioned the New Brunswick government on the grounds that his family had upheld the conditions of their 1767 grant by the Nova Scotia government and therefore Butler’s land defaulted to Owen. In his land petition to the Surveyor General of New Brunswick, Owen recounted that “upon the Arrival of your Petitioner in the [said] Island,” Owen had “found one Gillam Butler in Possession of Part of it.” The petition does not offer an explanation of how Butler managed to assume possession, other than by squatter’s right of occupancy. What the petition does tell us is that Butler “refused your petitioner the peaceable possession of that part which he [Owen] has right.” Owen’s claim to the land was brought before the council, and it was affirmed, on the grounds that Butler “got Possession partly by Force, partly by virtue of a Sheriffs sale under a Provincial Act, contrary to Justice and Equity.”

The ordeal of Gillam Butler is strange. His appearance before the Supreme Court of New Brunswick is not unknown to historians, but there is little work that examines the lead up to his trial, his escape, recapture, and later disputes over his property on Campobello. W.S. MacNutt, Ann Condon, Joshua Smith, and others have all noted that Butler’s illicit actions were indicative of tensions created by the new border, competing American and British interests, and the profitability of illicit trade in the Passamaquoddy. There are still many unanswered questions surrounding the case and its aftermath, but investigation into Butler’s life shows the conflicting visions for loyalist New Brunswick.

Butler’s experience demonstrates how a fluid border shaped his loyalist identity, the utility of a language of loyalism, and the ways that less well-known loyalists disrupted the interests of the New Brunswick elite, and British authority more generally. Loyalist smugglers like Butler were acutely aware of how to exploit corrupt Customs Houses, but his choice to sail for Saint John as opposed to St. Andrews suggest that Butler was also manipulating differences between British and American-born loyalist officials. Butler expressed a different, more American vision of New Brunswick in his correspondence to Chipman prior to his capture, and like so many others who resided in loyalist borderlands such as Campobello Island, he maneuvered between two empires, multiple communities, and in doing so captured the attention of some of the prominent names in Loyalist Studies and early New Brunswick history. It remains unknown if Butler ever managed to sail for England as he had advertised in the Royal Gazette, or if he returned to Campobello to live out his life in New Brunswick. Census records for the Passamaquoddy townships collected by the Massachusetts state government give no mention of anyone named Butler, nor does he or any of his potential descendants appear as tenants when Captain Owen’s son, William Fitz-Willam, assumed proprietorship of Campobello in 1835. Gillam Butler’s story is interesting because his attempt to gain a false register at the Saint John Customs House made headlines, became a point of geopolitical importance for Thomas Carleton in Fredericton, and even appeared upon Lord Sydney’s writing desk in London. The pull of illicit trade did not transcend Butler’s loyalism so much as it became a complicated element within it. Challenges to imperialist elites and their visions for New Brunswick came in all forms, making smuggling only a more tangible aspect of the American enterprising spirit that Governor Carleton and his peers sought to extinguish. Butler was adamant in his complaint that the American interest needed to be better served by government in New Brunswick and this was as much a commercial ploy as it was a cultural tether that connected him and thousands of other loyalists refugees to the United States after 1783. Loyalism existed in a constant state of negotiation that cannot be simplified as polarities either in favour or disfavour of imperial authority. Afterall, loyalist refugees were also Americans who likewise experienced Britain’s unconstitutional actions and the civil war which it ignited. How Butler’s story fits within longer histories of early New Brunswick, and Loyalists Studies generally, requires further analysis.

Richard Yeomans is a PhD candidate in the Department of History at the University of New Brunswick. His research examines science and society in 19th century New Brunswick. He is the co-creator of the New Brunswick Storytellers Project. More information on this project can be found at http://atlanticdigitalscholarship.ca/new-brunswick-storytellers-project/.

Primary Sources Used

Edward Winslow Papers, UNB Archives & Special Collections

New Brunswick, Lieutenant Governor, Letter Books : 1784-1812, The Loyalist Collection.

New Brunswick, Supreme Court, Minutes: 1785-1829, The Loyalist Collection.

New Brunswick, Surveyor General, Land Petitions: 1783-1834, The Loyalist Collection.

Nova Scotia, Land Records, Nova Scotia Land Papers 1765-1800, The Loyalist Collection.

The Royal Gazette and New Brunswick Weekly Advertiser, Microforms Newspaper Collection, UNB Libraries.

Ward Chipman Muster Master's Office, 1777–1785, Library and Archives Canada.

Secondary Sources Used

Rebecca Brannon, From Revolution to Reunion: The Reintegration of the South Carolina Loyalists (Columbia, University of South Carolina Press, 2016).

Ann Gorman Condon, The Envy of the American States: Loyalists Dreams for New Brunswick (Fredericton, NB: New Ireland Press, 1984).

L. K. Ingersoll, “OWEN, WILLIAM,” in Dictionary of Canadian Biography, vol. 4, University of Toronto/Université Laval, 2003–, http://www.biographi.ca/en/bio/owen_william_4E.html.

Joshua M. Smith, Borderland Smuggling: Patriots, Loyalists, and Illicit Trade in the Northeast, 1783-1820 (Gainesville, University of Florida Press, 2006).

Esther Clarke Write, The Loyalists of New Brunswick (Moncton: Moncton Publishing Co., 1972 [2nd Ed.]).

Add new comment