- Submitted on

- 0 comments

The following post features one of the loyalists who is portrayed in our upcoming story mapping project "New Brunswick Loyalist Journeys." Please watch this page for further announcements on this exciting, new way to understand the lives and experiences of loyalists.

Each loyalist who arrived as a refugee to the Canadian colonies had a unique story. Many of their narratives have remained obscured in history, but recovery of their stories is possible, expanding our understanding of diversity among loyalists. The life of Lieutenant Samuel Richard Wilson provides an excellent example of a distinct background and experience possessed by an individual loyalist. Although the documentary sources for Wilson’s early and later life are scarce, his time in North America is well documented, often by his own hand.

Most likely born in Ireland and a Catholic, Wilson came to America in 1777 as a British half-pay veteran officer. A career army officer, Wilson appeared at the rank of lieutenant or adjutant throughout his time in North America. He also acted as an attorney and petitioner for others while in New Brunswick. His status as a Catholic in the British Army is particularly interesting, as Irish Catholics could not hold firearms or serve in the British armed forces officially until 1793.

During the voyage across the Atlantic, Wilson’s ship was captured by an American privateer, but he managed to make his way to Philadelphia to join the Roman Catholic Volunteers. He was “taken . . . Prisoner by a Boston Privateer by which accident he lost all his cloaths and other Property,” according to his later loyalist claim. The Roman Catholic Volunteers was an unusual loyalist regiment in that it was made up of only Catholic soldiers and was disbanded after only a year of service due to unruly behavior.

(Library and Archives Canada, British Military and Naval Records)

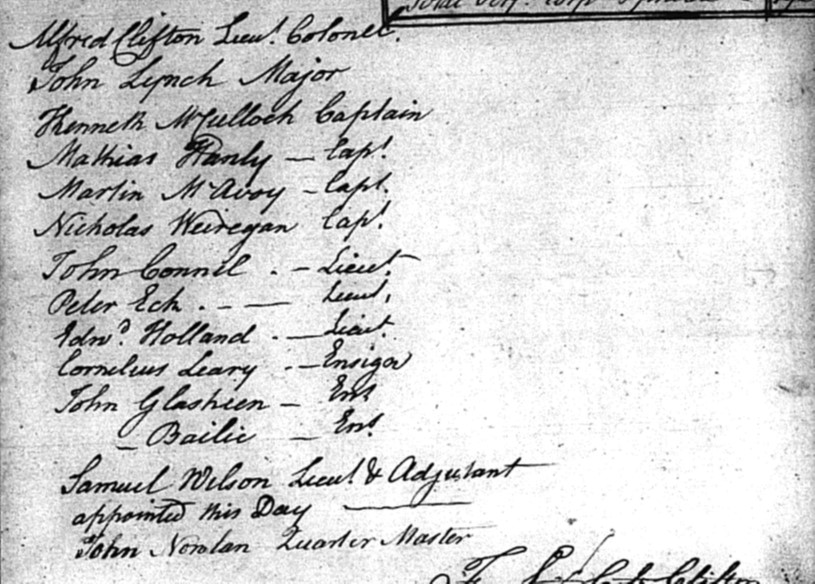

During the subsequent years of the American Revolution, Wilson was transferred to the 2nd Battalion of the New Jersey Volunteers where he had as series of problems disciplining subordinates while acting as temporary adjutant. These conflicts ended in a court martialed for conflicts in spring 1780 with the formal charge of “Disobedience of Order and disrespectful behavior on the Parade, to the Officer Commanding” for which he was found guilty and publically disciplined.

(British Military and Naval Records, “C Series”: 1767-1899, v. 1873 p.6.)

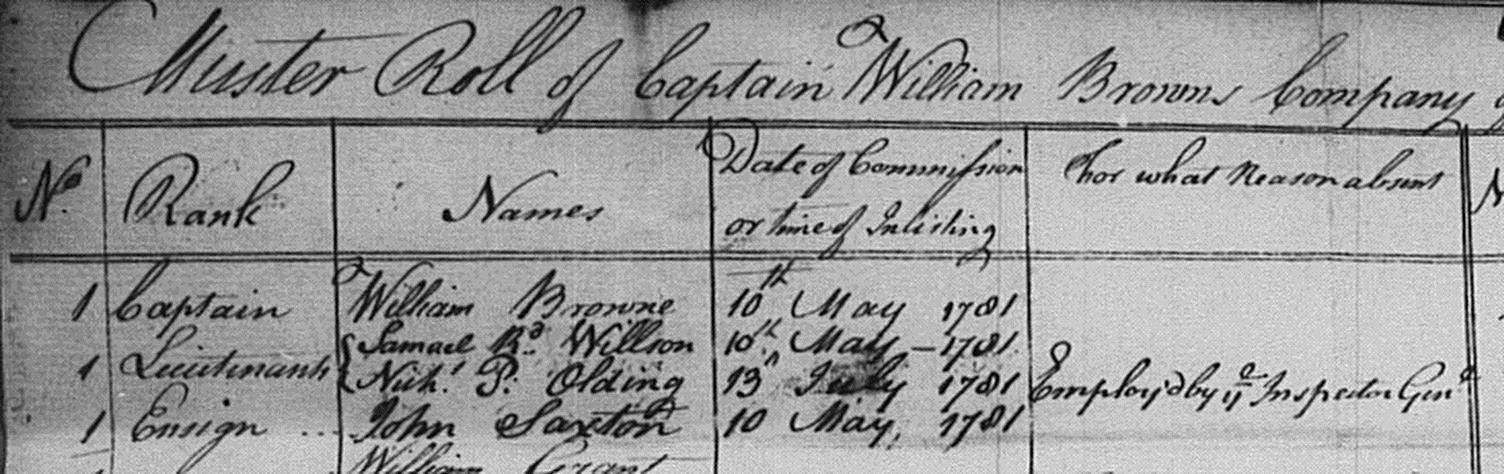

The following year, on May 10, 1781, Wilson was moved to the Royal Garrison Battalion, still as lieutenant. The Royal Garrison Battalion was made up of mainly invalided British officers, “. . .better calculated for the duty of a Garrison, or the defence of an Island or Fort. . . The Officers for this Corps should perhaps be Compos’d of such as are worne out, or disabled & of long Service . . .” Therefore, Wilson must have been deemed unfit for full duty in some way.

The reason behind Wilson’s frequent transfers amongst regiments did appear to have something to do with his ability as an officer. It has been noted that some officers of provincial loyalist regiments were regular British officers, but perhaps not excellent examples; Edward Winslow complained several times about their performance, calling them “Coxcombs, Fools and Blackguards.” It is also not fully clear as to why Wilson was considered widely to be a loyalist, as he had not arrived in the American Colonies until after the outbreak of war, but he did submit a claim to the Crown.

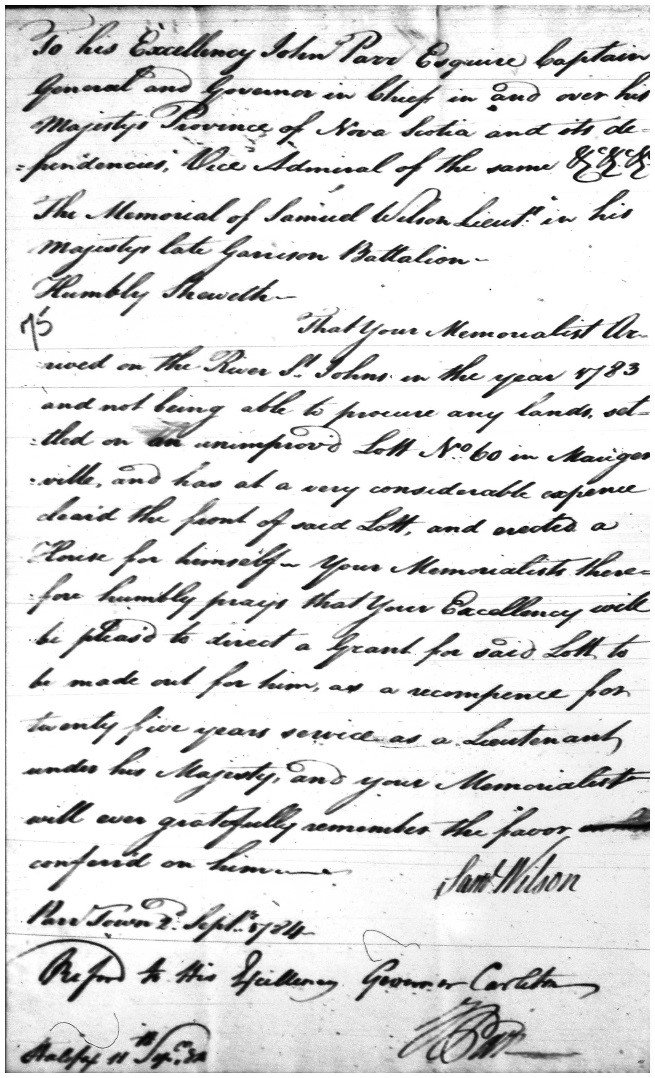

At the end of his service in 1783, Wilson attempted to settle in York County, New Brunswick, Canada. Wilson disembarked at “River St. John” from the ship the King George, assumedly with the plan to farm in New Brunswick. He first settled in the existing community Maugerville, then had concerns with land on the Nashwaak River, and finally was given grants upriver in what became Queensbury Parish. Wilson was a prolific producer of land petition documents, and thus leaves a good record of his actions from the years 1784 to 1786.

While in New Brunswick, Wilson was actively involved in petitioning Governor Carleton for various personal and group land grants, demonstrating connections with both existing inhabitants and new settlers in the region. The mass of documents created by Wilson due to various land transactions shows that he was actively participating in the settlement of New Brunswick for a period of time.

(New Brunswick, Surveyor General, Land Petitions: 1783-1834)

The activities of Wilson during 1787 and the following years are clouded. By 1789, new petitions were being made for land which had been granted to Wilson, mainly in Queensbury Parish. For example, In April 1820, Abraham Sloot petitioned for land formerly granted to Wilson in Queensbury of 364 acres in the grant of John Parker and others which “has been Escheated, and now remains ungranted; and is yet in a state of nature.”

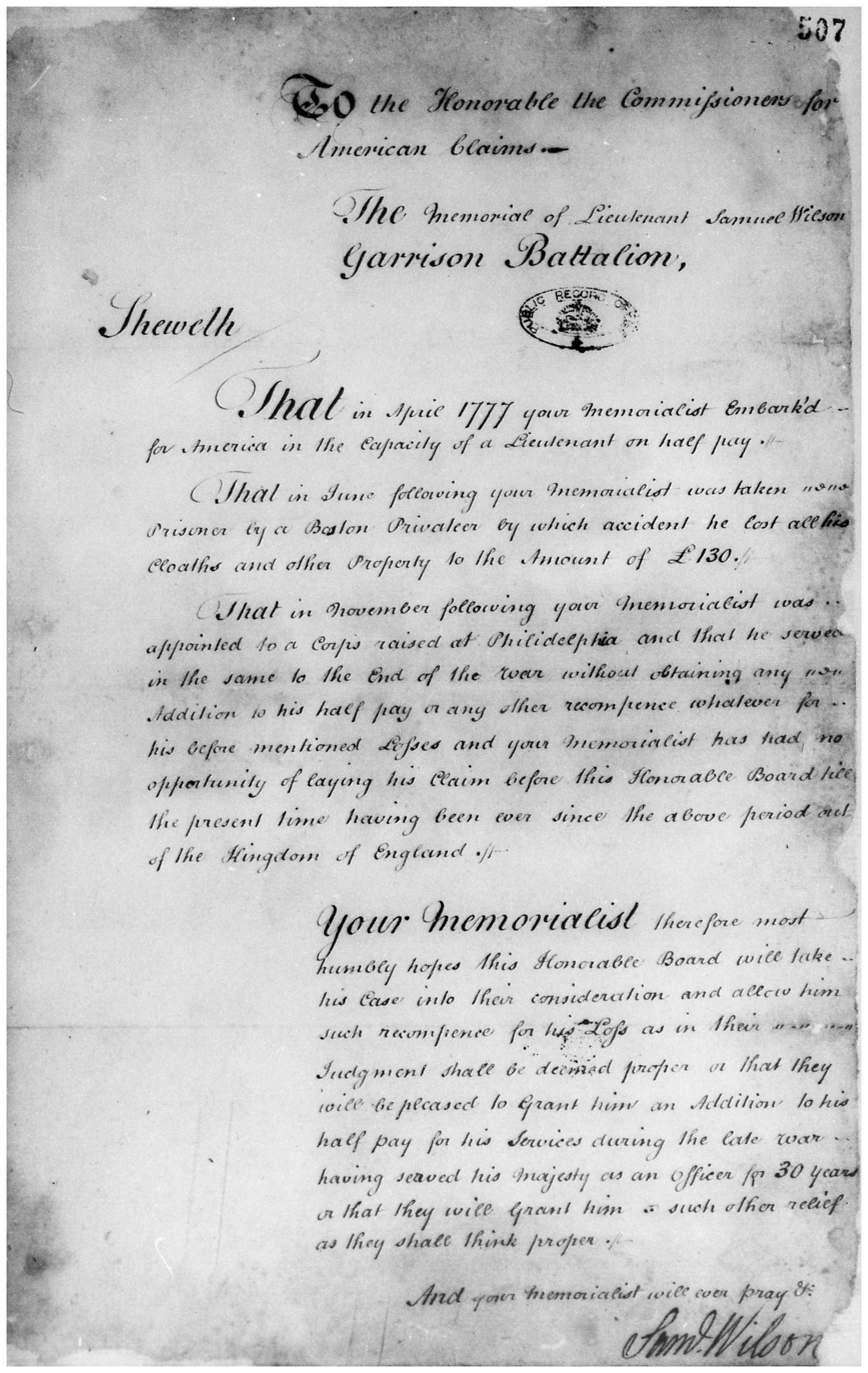

The last document found for Wilson was his undated claim for losses suffered as a loyalist. The statement in the claim that “having served his Majesty as an Officer for 30 Years” makes the potential date for the claim 1789, as he had written in a New Brunswick land petition in 1784 that he had served for twenty-five years. It is very possible this document was written after a return to England; he explained of the lateness of the claim, he had “no opportunity of laying his Claim before this Honorable Board till the present time having been ever since the above period [out] of the Kingdom of England,” insinuating he had returned. Interestingly, he does not specify what corps he joined in Philadelphia and said that he “served in the same to the End of the War,” glossing over his unsuccessful time in the New Jersey Volunteers and his court martial. He was requesting more than half pay for all his time served with the British army and in the provincial regiments, and to be compensated for his goods taken by the American privateer in 1777. The decision was that what he lost is a fortune of war and therefore could not receive compensation.

(Great Britain. Audit Office. Claims, American Loyalists : Series II (AO 13) : 1780-1835.)

Wilson’s character boldly emerges from the pages of basic primary documents. He faced many challenging experiences while in the North American colonies, perhaps because of his religion and ethnicity, but also likely reflecting his approach and personality. Through a few common primary documents, Wilson’s adventure in North America and his periphery status as a loyalist is revealed. His individuality shines from the everyday pages.

MAJOR SOURCES

Great Britain. Audit Office. Claims, American Loyalists : Series I I (AO 13) : 1780 - 1835.

New Brunswick, Surveyor General, Land Petitions: 1783-1834.

The On-Line Institute for Advanced Loyalist Studies.

W. O. Raymond, Roll of Officers of the British American or Loyalist Corps, Provincial Archives of New Brunswick website.

B. Wood-Holt, The King’s Loyal Americans, (Saint John, N.B.: Holland House, 1990).

Esther Clark Wright, The Loyalists of New Brunswick, (Wolfville, N.S., Canada: E.C. Wright, 1981 printing, 1955).

Leah Grandy holds a PhD in History and works as a Microforms Assistant at the Harriet Irving Library.

Add new comment