- Submitted on

- 0 comments

Many history enthusiasts and genealogists are drawn to cemeteries and graveyards, often to the dismay of their companions and families. Grave markers can prove to be great sources of information when doing historical biographies, family history, demographic history, and cultural history of settlers in eastern North America during the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries.

What can you learn from grave markers?

Information on grave makers can indicate general demographic patterns if they are not available through historical documents: number of burials per year, deaths during epidemics, life expectancy, disposable wealth levels in the community, etc.. Of course, it has to be considered that not all burials would have received markers and not all markers survive to the present day.

Text on Grave Markers

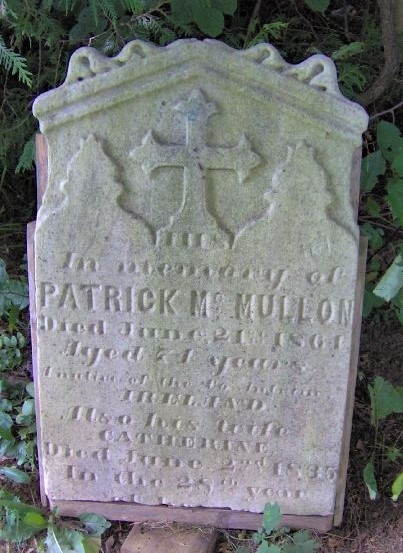

Epitaphs sometimes offer short profiles of individual lives that could include basic biographic information such as place of birth, occupation, cause of death, accurate birth/ death dates, and family members. The script on a women’s marker most usually attached her to a man (a husband or father). Typical beginnings of epitaphs in the late eighteenth century Maritimes included “Here lies” or “Sacred,” with “In memory of” becoming more popular in the nineteenth century. In earlier marker text, a common inscription would be, “Here Lyes Buried the Remains of. . .” Of course, more text and detail could be fit onto larger, more expensive markers, including a verse of poem or from the Bible. The same changes in writing style, punctuation, spelling, and word use that occurred over time in other forms of writing are apparent in grave markers. It is important to note that markers may not have been produced at the exact time of death and some may have been later replaced.

Shape & Materials

The materials used in the making of grave markers show import trends in trade and transportation networks, Boston being the general centre for gravestone manufacture in the Atlantic World during the late eighteenth and early nineteenth centuries. Local materials were often used on early colonial markers and some later ones as well. Early marker shapes echoed the feel of a bed or doorway with a three-lobed or “tripartite” topper being most common, with more elaboration and variety appearing during the eighteenth century in shape. Around 1800, preference switched to a squared-shouldered, clean, Neo-classical influenced shape. Marble or white stone was increasingly used in the first half of the nineteenth century as a material, while granite was generally not used in markers in eastern North America until the end of the nineteenth century, as it was hard to quarry without mechanization. For an exploration of the location of materials used for the “Titanic” gravestones in Halifax, Nova Scotia, see “Titanic gravestone mystery led to five year search.” Change over time in cultural preference and availability of material and skilled labour can be traced through the material, size, shape, text, and decorations of markers.

Symbology of Grave Markers

Both academic and popular interest has been focused upon the symbology of carvings on grave markers as examples of settler art and culture in North America. Through analysing the images found on grave makers, possible cultural and spiritual influences can be gleaned from the iconography.

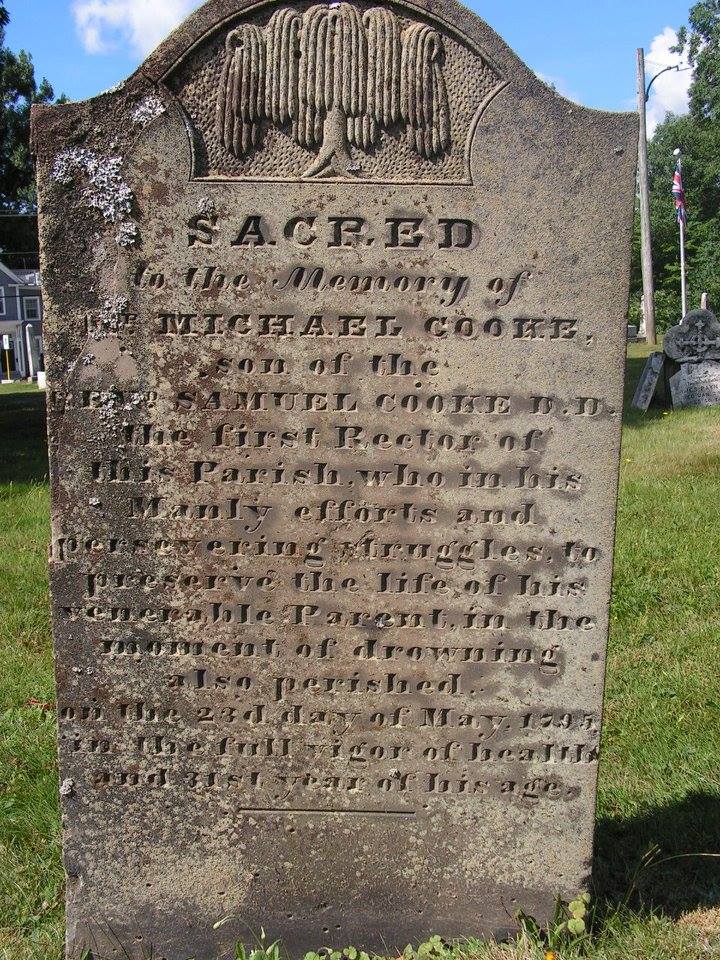

Two of the most well-known symbols used on grave markers in the eighteenth-century Atlantic World were “death’s heads” and “soul effigies.” Pre-1830, symbols on grave markers had a strong focus on mortality and often included text which was meant to be cautionary to the living. During the progression of the century in eastern North America, there was a transition from a preference to death’s head, which could exhibit various expressions and styles depending on the carver, to soul effigies with intermediate modifications. As death’s head morphed into a winged head, sometimes called a “soul effigy” to resemble more of a cherub or angel, the symbology seemed to shift alignment towards resurrection.

Other symbols which appeared in eastern North America grave markers during the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries: crossbones (a simple mortality symbol); hourglass (showing the limited time of life), peacocks (representing immortality), crowns (for triumph of death or triumph over death), tulips (showing Dutch or German influence), and shell or fan motif (an ancient symbol of resurrection). Some symbols could represent both mortality and resurrection. Mortality symbols did not entirely disappear by the end of the eighteenth century, but North America did follow the trend toward soul effigies that was occurring in Great Britain, with a primitive soul effigy transition between the two types of symbols.

Directly after the American Revolution during the 1780s and 1790s, the absence of symbols on grave markers was very common. Also in the post-war period, the Neo-Classical movement—constituting a revival with an adaptation of classical culture from Ancient Roman and Greece—had a huge impact on art and material culture in North America and Britain, and this was reflected in funerary decoration. Urns and urn-shaped lamps as marker symbols became very popular, particularly with a flame on top as the “lamp of life” representing immortality. The urn as regular device of grave decoration was well established in the Maritimes by the 1800s. Willows were the other hugely popular symbol to emerge from the Neo-Classical influence. The urn and willow were often used in combination, while the use of soul effigies declined as popular tastes moved toward sentimentality.

Grave marker symbols associated with Christian religious traditions included a hand pointing upward to heaven, a lamb (the Agnus Dei), crosses, the Sacred Heart, or the Roman Catholic use of “IHS” (a monogram from Greek symbolizing Jesus Christ). Also, flowers were often used on the markers of women and children during the nineteenth century.

Grave Carving Traditions

The stone marker carving traditions of New England, which in turn were influenced by trends in Great Britain and immigrant carvers from England, dominated North America, including South Carolina, Georgia, and the Maritime colonies up until the 1790s. Gravestone carving in the early settler period of North America, especially in less populated areas, was often a side job for stonemasons and other craftsmen. Individual styles or school of marker designs started appearing in the first half of the eighteenth century in New England, New York, and New Jersey and can often be traced.

For example, a carver of a number of grave markers found in Annapolis County, Nova Scotia which featured distinctive cherub’s heads from around the year 1800 may have worked out of Saint John, New Brunswick, across the Bay of Fundy, as similar markers are found in the Old Loyalist Burying Ground of Saint John.

From inscriptions, symbology, physical attributes, and carving traditions, grave markers can offer both personal and general social information from the past.

Look for our next post: Research Finds in the Graveyard, Part 2.

Leah Grandy holds a PhD in History and works as a Special Collections Assistant at UNB Libraries.

Add new comment