- Submitted on

- 0 comments

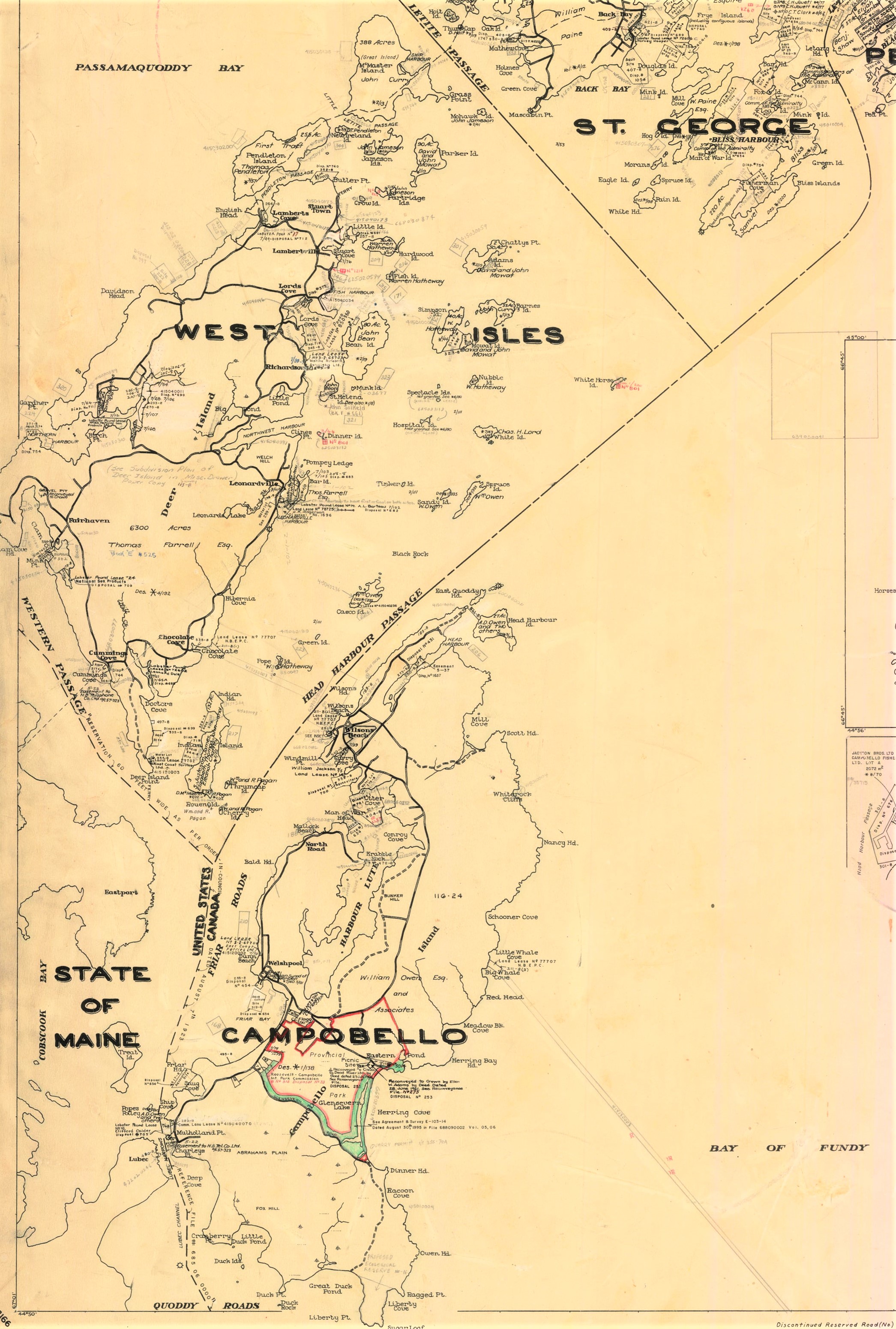

To fully grasp the kind of place that Gillam Butler lived, it is useful to imagine New Brunswick’s southwesterly edge, including the Fundy Isles, as a kind of loyalist borderland. The fishing outports of mainland Charlotte County, Grand Manan, Deer and Campobello islands have long been sites to congregate in Indigenous trading networks, transatlantic commerce, and European imperial warfare.

By 1783, the Passamaquoddy region was situated between two competing empires – the United States and Great Britain – making illicit trade highly profitable and political jurisdiction all the more complicated. As Joshua Smith writes, “the more government forces attempted to halt unregulated trade, the more apparent it became to locals that the state was an unwelcomed and alien force” (Borderland Smuggling, 2006; 11). For Butler, and many others like him, islands such as Campobello represented an important intermediary location between American enterprise and British law. As the concept of a loyalist borderland suggests, Campobello and loyalists like Gillam Butler were defined by the social, political, and cultural consequences of civil war that made smuggling a necessary component to life in New Brunswick. However, participation in illicit trade did not completely contradict Butler’s loyalist identity but instead demonstrates how loyalism existed in shades of grey. Even officials such as William Wanton, the American-born Customs Officer at Saint John, was lax in his duty to prevent contraband from entering port. This helps explain why Butler chose to sail further to Saint John, rather than the closer Customs House at St. Andrews controlled by British-born merchants. When Butler was caught at the Saint John Customs House in April of 1786 trying to import American whale oil as British American produce, Governor Carleton’s efforts to make an example of Butler is indicative of much larger tensions in New Brunswick.

Acting quickly, the governor commissioned Robert Parker, another Saint John customs officer, to investigate Butler’s dealings in Charlotte County from St. Andrews. What Parker discovered was surprising, given that Butler appealed to the Nova Scotia government for land so as to prevent his family from becoming destitute after their evacuation from New England. In a summary of the court case in The Winslow Papers, Parker found that Butler was operating a brigantine named ironically the Carleton, a pre-revolutionary vessel that had been purchased, refurbished, and illegally re-registered as the Campo Bello in 1785. Ward Chipman, the prominent loyalist and New Brunswick’s Attorney General, was directed by the Governor to prosecute Butler, and testimony from William Pagan, a leading Scottish merchant of St. Andrews, strengthened the case against him in New Brunswick’s Supreme Court on 2 May 1786. Charged with swearing falsely, Butler was found guilty, fined £500, and sentenced to three months in prison. This was an abnormally harsh sentence for what was technically only a misdemeanour (swearing falsely). Thomas Carleton would later complain, in another letter to Lord Sydney, that he had originally wanted the Attorney General, Ward Chipman:

To prosecute Mr. Butler for both for the fraud and the perjury; He [Chipman] was, however, of opinion that, as the Statute had not expressly injoined [sic] the penalty for swearing falsely in the case of registers, the utmost he [Chipman] could do was to indict the Offender for a misdemeanour. (Thomas Carleton to Lord Sydney, 13 October 1786)

What followed was something straight out of an Alexandre Dumas novel. After Butler was found guilty, he staged an escape from the Saint John jail, and by way of sea, seemingly returned to Campobello Island.

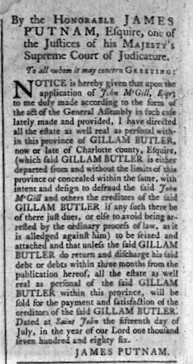

Two months later, in a July issue of the Royal Gazette, Judge James Putnam, who presided over Butler’s trial before the Supreme Court, published an ad calling on the creditors of “Gillam Butler, now or late of Charlotte County, which [he] is either departed from and without the limits of this province or concealed within the same.” If Butler did not pay the court imposed fine, his lands would be seized and sold at auction, but it was no secret to anyone that the border presented criminals like Butler with the opportunity to disappear if needed. Even Judge Putnam conceded that the border provided no limitations upon the mobility of loyalists, smugglers or otherwise. Refugees who resettled in New Brunswick maintained connections to their American life, often through kinship networks, but also commercial networks that also engaged in smuggling and piracy. Many loyalists even returned to the United States in the years following the Revolution, reintegrating, and finding ways to live with neighbours that once persecuted them.

Gillam Butler, however, had not crossed into the United States, but instead remained in New Brunswick. In a response to Putnam’s ad, Butler placed a notice in the Royal Gazette in August announcing his intent to pay his creditors and his wish to receive immediate payment from those indebted to him. The ad, which appeared in the 15 August issue of the paper, was post-dated “Campo Bello, 10 August, 1786.” Though Butler likely meant Campobello Island (contemporaries did refer to it as “Campo Bello”), there is good reason to speculate that he wrote the ad from the eponymous brigantine, given his recent flight from Saint John, and emphasis that Christopher Sower, the printer, placed on the name in Butler’s ad; unique when compared to similar notices published in the Royal Gazette that year.

In the notice to his creditors and debtors, Butler also expressed his plans “to depart the province and to embark for England, as soon as the adjustment of his affairs will allow.” At this point, his name was publicly tarnished, and readers of the Royal Gazette were well aware of his criminal actions, trial, and evasion of the law. In a letter to the printer of the Royal Gazette, appearing in the issue immediately following Butler’s notice, one observer, writing under the pseudonym ‘ROMANUS,’ condemned smugglers and their “breach of civil institutions.” Such injury towards government was an attack on “the solemn compact” of public interest, according to Romanus, critical of the rogues who “pronounce it [smuggling] to be only a game at hazard, and assert that when there is a penalty adequate to such a breach, a violation of the law, or an artful attempt to evade it,” such persons must suffer the penalty of the law. It reads as no coincidence that Romanus’ damning portrayal of crime and evasion perfectly mirrors the recent escapades of Gillam Butler, who was convicted and fled the law in similar fashion. What is striking, is the accuracy with which Romanus’s critique of legal penalties mirrors Carleton’s frustration over Chipman’s inability to charge Butler more severely:

If a penalty is such as to leave a possibility for a man to evade or disobey legal authority in any instance to his advantage, the punishment is to[o] feeble, and it must have been from a mildness in Government, that a more severe one has not been applied.

It is unclear who Romanus was, but it stands to reason that the writer of an opinion letter so critical of smuggling and piracy was also well aware of the limitations that prevented Chipman from indicting Butler with anything other than a misdemeanour. Carleton’s heavy hand was certainly not a sign of mildness in government, but rather a strong indication that the executive in New Brunswick would make every attempt to reinforce its own power, on land, and at sea.

Butler’s notice to the Royal Gazette and a letter he wrote to Ward Chipman in 1785 prior to the first election in the province are the only two records that I could locate in The Loyalist Collection that Butler unmistakably produced. The bulk of Butler’s presence in the archive was found in the records of the New Brunswick Supreme Court, the Carleton Papers, the Winslow Papers, the Lawrence Collection (which is held by LAC), and newspapers such as the Saint John Gazette and Royal Gazette.

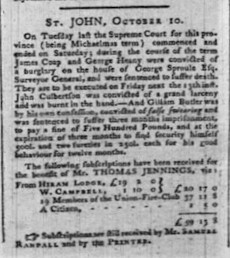

In later issues of those papers, there are notices to the public of Butler’s reappearance in front of the Supreme Court from 10 October 1786, this time noting that he pleaded guilty to swearing falsely, and testimony from the Sheriff of Charlotte County, Thomas Wyer, which substantiated it. Three days later, Carleton would write to Sydney, summarising Butler’s trial, the original conviction, the problems of the statute as it related to swearing falsely to acquire a register, and Butler’s escape from the Saint John jail, which according to Carleton was only an “attempt… but [Butler] was retaken.”

After Butler’s ad in the Royal Gazette, he disappears from the record until September 1787, when Sheriff Wyre placed a notice of auction in the Royal Gazette of lands formally belonging to the convicted smuggler – “[A] tract of land situate in Campo Bello, containing by estimation 2500 acres… among which are several dwelling houses, and an excellent Grist Mill and Saw Mill.” When Butler was granted this land, or if indeed he ever was granted such an estate, is explored in the next post.

Next week: Loyalist Borderlands on Campobello Island: The Ordeal of Gillam Butler, Part Three

Richard Yeomans is a PhD candidate in the Department of History at the University of New Brunswick. His research examines science and society in 19th century New Brunswick. He is the co-creator of the New Brunswick Storytellers Project. More information on this project can be found at http://atlanticdigitalscholarship.ca/new-brunswick-storytellers-project/.

Add new comment