- Submitted on

- 0 comments

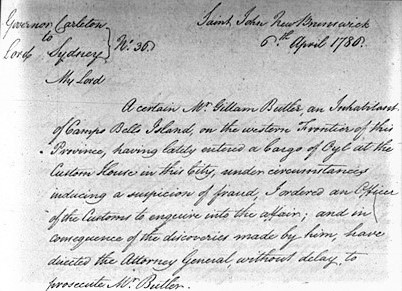

In April of 1786, writing to Lord Sydney, the British Home Secretary, New Brunswick’s Lieutenant Governor Thomas Carleton complained about “a certain Mr. Gillam Butler, an Inhabitant of Campo Bello [sic] Island.” The Governor, a staunch imperialist who surrounded himself with likeminded loyalist refugees, informed Sydney that Butler was caught by officials at the Saint John Customs House swearing a false oath in an attempt to gain a register (a list of commercial goods on a British vessel) to sell his cargo of American-produced whale oil. “Under circumstances inducing a suspicion of fraud,” Carleton wrote, “[I] ordered an Officer of the Customs to enquire into the affair; and in consequence of the discoveries made by him, have directed the Attorney General, without delay, to prosecute Mr. Butler.”

At a glance, the Governor’s letter to Sydney does not seem unusual to anyone familiar with scholarship on the loyalists. Thomas Carleton despised any challenge to British authority in New Brunswick and made every effort to curb illicit trade between the new colony and the equally new United States. Elite loyalists were inclined to support Carleton for much the same reason, but particularly because smugglers like Butler presented a challenge to the elite’s vision for New Brunswick, which was to build the “most gentleman-like [society] on earth.” Carleton’s letter to Sydney, however, is an important reminder that the majority of the American loyalist refugees who wound-up in the Maritimes did not share in the more grandiose visions of the loyalist province. Between April of 1786 and October of 1787, Butler and his ordeal preoccupied some of the most prominent names of loyalism who made up a powerful elite minority in New Brunswick: many of whom went to great lengths to eliminate the likes of Gillam Butler. His story, like that of so many of the loyalist refugees that resettled along the Fundy coast of New Brunswick, was the result of a porous new border, competing identities, and enduring connections with the United States after violent civil war.

Using various fonds located in The Loyalist Collection at UNB Libraries, this series of posts chronicles the early life, trial, and pursuit of Gillam Butler as retold through record fragments. His peculiar story leaves several questions unanswered but is important nonetheless because of the impressive web of connections it reveals and the interesting choices he made. Unlike the political elites who pursued him, Butler has not left loyalist scholars an extensive written record. Instead, his experience in the infant colony of New Brunswick must be retold through numerous pieces and clues that, when woven together, demonstrate the immense fluidity of New Brunswick’s southwestern edge and its impact upon our understandings of loyalists and loyalism in the late eighteenth century.

To tell the story of less well-known loyalists using the records produced by the elites who observed them presents an important question of voice and comes with its own set of limitations. This question is only further complicated when using records produced by the individuals who wanted Butler punished for his crime and others whose commercial interests Butler was in competition with. New Brunswick’s early years were defined by political and commercial jockeying for power, not just amongst members of the House of Assembly and Executive Council, but also between British and American-born merchants dominating the ports of St. Andrew’s and Saint John, respectively. Importing commercial goods into the new province was a lucrative business for men like Gillam Butler, who appealed for government assistance as a loyalist refugee but who’s ambitions depended upon American enterprise. For this reason, Butler is an excellent example of New Brunswick’s hybrid loyalist identity. He was an American merchant who, for one reason or another, chose to remain a British subject after 1783, but was obstinate in his belief “that American influence should prevail in the government [of New Brunswick].” Butler’s refusal to sever his American ties would later become the subject of much anxiety for Carleton and the loyalist elite.

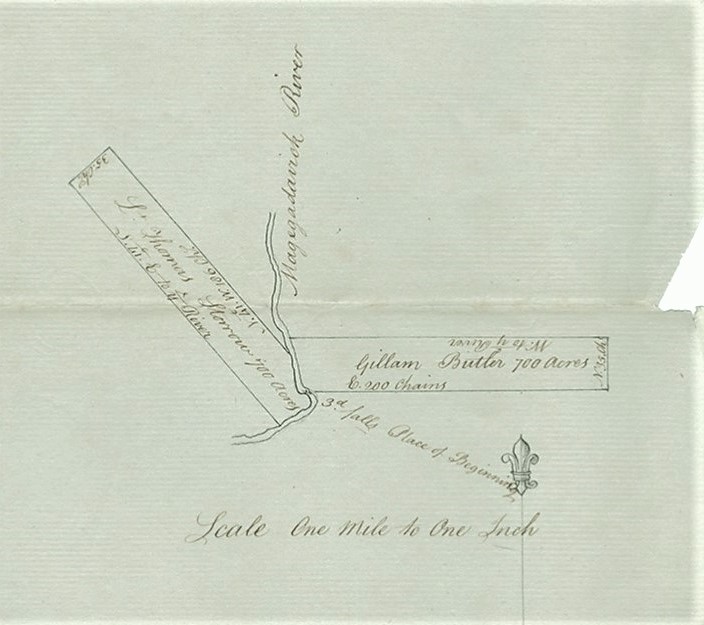

According to Esther Clarke Wright’s ‘Red Loyalist Bible,’ (Loyalists of New Brunswick, 1954) Gillam Butler was first evacuated to Halifax from Boston in 1776. A New Hampshire merchant, Butler petitioned the Nova Scotia government for land in compensation for his loss of property “in consequence of his attachment to the King’s Government.” His petition outlined his need for land to support his wife (unnamed), four children, and four “servants.” Land grant records available through the Nova Scotia Archives indicate that Butler and his family were given land in the Passamaquoddy Bay region just after the American Revolution. He was awarded a tract of 700 acres on the Magaguadavic River, above present-day St. George, in Charlotte County.

Butler’s land was reregistered after New Brunswick was partitioned from Nova Scotia in 1784, though there is no evidence to suggest that he, or his family, ever resided on the land detailed in the grant. The archival record shows that Butler took up a sizable estate on Campobello Island where he returned – if, indeed, he ever stopped – to his life as a merchant, becoming a smuggler of American produce and in direct competition with the British merchants of St. Andrews.

Next week: Loyalist Borderlands on Campobello Island: The Ordeal of Gillam Butler, Part Two

Richard Yeomans is a PhD candidate in the Department of History at the University of New Brunswick. His research examines science and society in 19th century New Brunswick. He is the co-creator of the New Brunswick Storytellers Project. More information on this project can be found at http://atlanticdigitalscholarship.ca/new-brunswick-storytellers-project/.

Add new comment