- Submitted on

- 0 comments

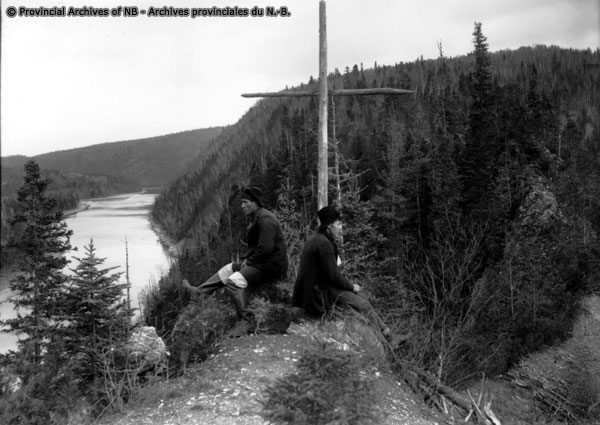

The real, daily interactions between indigenous people and setters of European ancestry in British colonies was an ongoing process and often involved a clash in lifestyles. Formation and negotiation of relationships between colonial groups were recorded through petitioning and court cases initiated by both indigenous and settler populations. The rough construction of these relationships can be observed within the court records of Northumberland County, New Brunswick.

The Court of General Quarter Sessions of the Peace for Northumberland County records consist of the minutes of the Court, with accounts of criminal and civil matters such as boundary and fishing disputes, appointment of officials, and the resolution of minor offences. Northumberland County during the period in which the records were created (1789 to 1807) was made up of communities which were termed “districts”. Northumberland was one of the original eight counties of New Brunswick when the province was set off from Nova Scotia, and during this time the county included territory which became Northumberland, Kent, Gloucester, and Restigouche Counties.

In these records, relationships between the indigenous populations (often distinguished with the terms “Indian”, “squaw”, and “Native Indians”) and “English” settlers (as they were usually described) were revealed through their involvement in the court system. A variety of strategies were employed by the people of Northumberland County and its adjudicators to deal with conflict between groups and individuals.

Violent Confrontations

A variety of cases involving indigenous people may be found in the early court records. For example, on January 18th, 1791, there was a complaint made by Barnaby Julian (“Native Indian”) that Peter Whitney and John Rogers “assaulted and abused” his wife, but the Grand Jury found there was not enough evidence to proceed to trial.

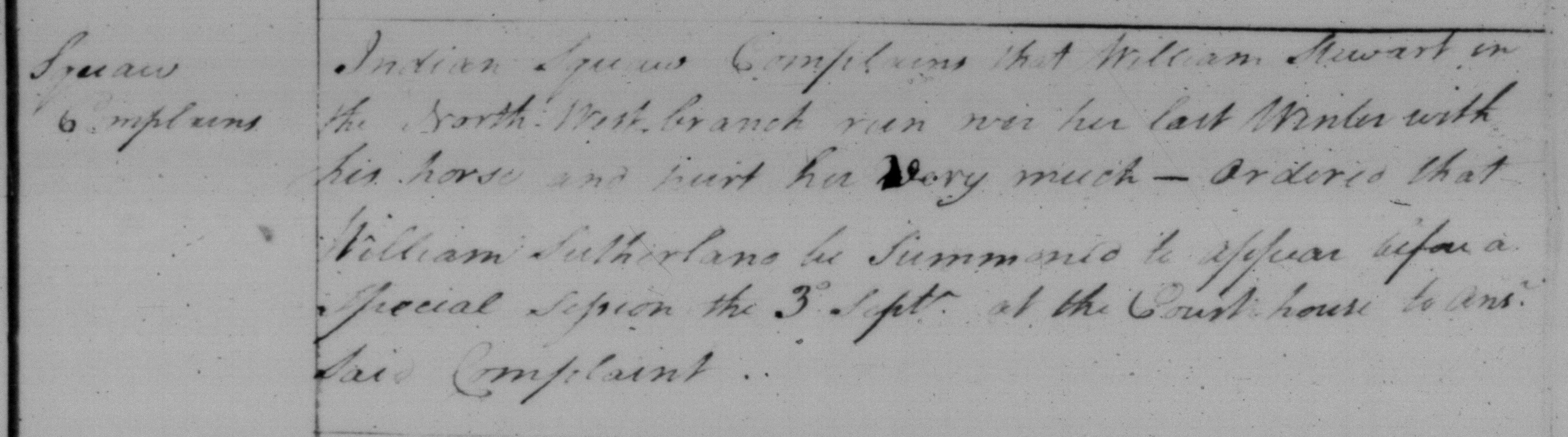

On August 7, 1807, the court recorded an “Indian Squaw complains that William Stewart in the North West branch run over her last winter with his horse and hurt her very much.” Stewart was ordered to appear before a Special Sessions of the Court to answer the complaint, and appeared on September 3, 1807. The victim was entered as “Molly Squaw” and appeared and gave evidence; the Court was satisfied that the accident was not it was not done willfully, but Stewart was still ordered to pay the woman compensation in “12.6 d [pence] store pay and costs”.

Canine Conflict

One of the issues which appeared frequently as a “bone of contention” between groups in the region interestingly concerned dogs. Joel S. Turner in March 1803 presented a petition to the Court from the inhabitants of Tabusintac with a statement of the costs sustained by “Indian dogs killing their sheep,” the result of which was the Court ordered the statement to be filed for consideration. On August 4, 1803, the court ordered that the “Indians prevent their dogs from doing mischief or killing sheep or cattle,” to tie up their dogs, and that the owners would be liable for any damages they caused.

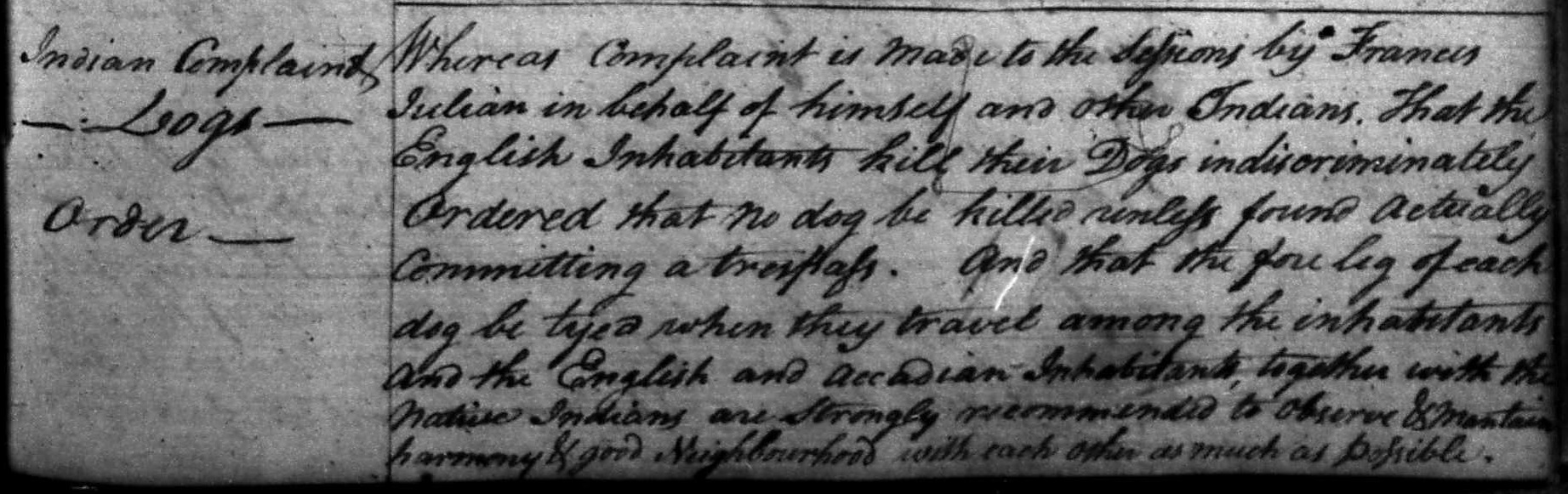

The topic was ongoing as two years later, on August 8, 1805, a complaint was made by “Francis Julian on behalf of himself and other Indians; that the English inhabitants kill their dogs indiscriminately.” It was ordered that no dog be killed unless found actually committing a trespass and “that the foreleg of each dog be tied when they travel among the inhabitants. It was also suggested that “the English and Acadian inhabitants together with the Native Indians are strongly recommended to observe and maintain harmony and good neighbourhood with each other as much as possible.”

Negotiating Through the Court System

When on August 4, 1803, a series of petitions again from the inhabitants of Tabusintac were submitted to the court complaining about the actions of indigenous people, the Court ordered that “the Indians not be molested or any trespass made by any of the English People upon the lands or waters licenced to them by government.” Above the licensed tract of land, waters and lands were to be shared by both groups. The Court also “strongly recommends both English and Indians endeavour to live peaceably.”

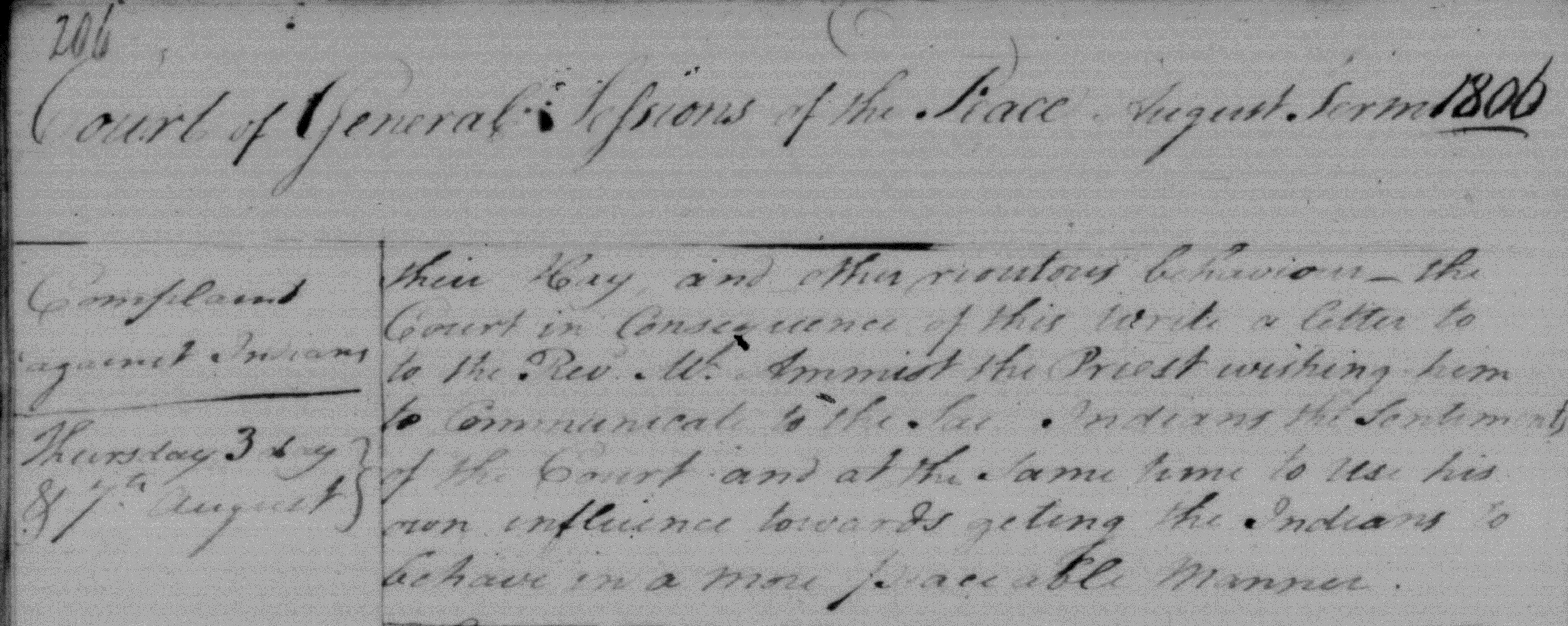

The flexibility in court recommendations to resolve group conflicts is often apparent. A complaint was made against the group of indigenous people at Eel River called “Nannequashes” on August 7, 1806, “that they molest English Inhabitants with their hay and riotous behavior.” The Court responded by writing a letter to Reverend Ammist, the priest in the area, “to communicate to the Indians to behave in a more peaceable manner.” The county court was able to act as intermediary to help establish relationships and terms between groups competing for resources within New Brunswick.

Although the Northumberland County court records are often brief in their notations, a sense can be gained of the complex economic, social, and cultural interactions which were occurring in the early nineteenth century. Indigenous people were drawn into the imposed, colonial judicial system, but they also made use of that system to assert their limited rights as well as their agency.

Note: The Northumberland County Court of General Quarter Sessions of the Peace Minutes: 1789-1807 are part of an ongoing project in the Harriet Irving Library’s Microforms Unit to make the rich material of the New Brunswick county court records available in a searchable form.

Leah Grandy holds a PhD in History and works as a Microforms Assistant at the Harriet Irving Library.

Thanks to the research and transcription efforts of Kimberly Vose Jones, Research Help Desk Assistant.

SUJBECTS: New Brunswick, law, First Nations, indigenous peoples, crime, fishery, dogs

Add new comment