- Submitted on

- 3 comments

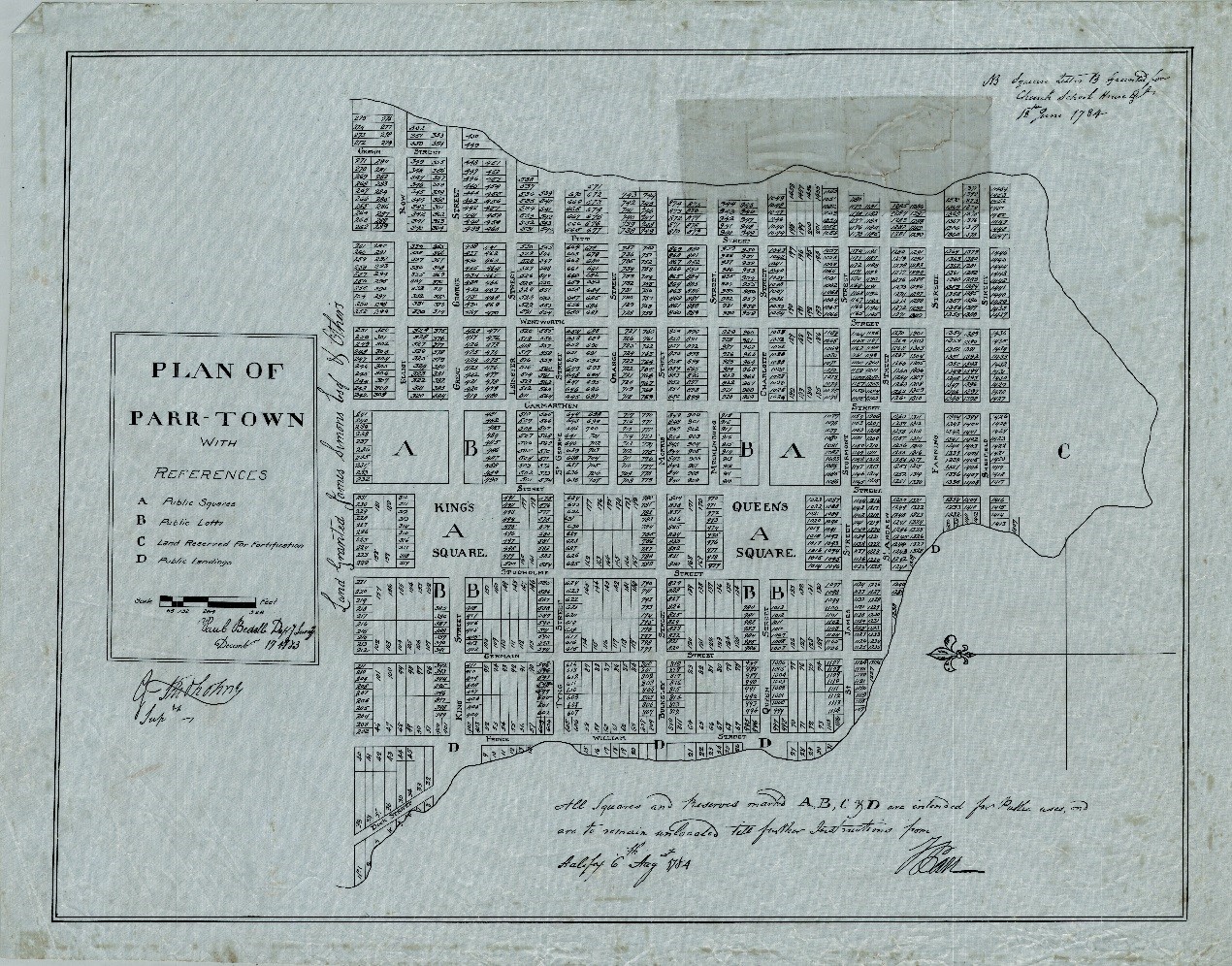

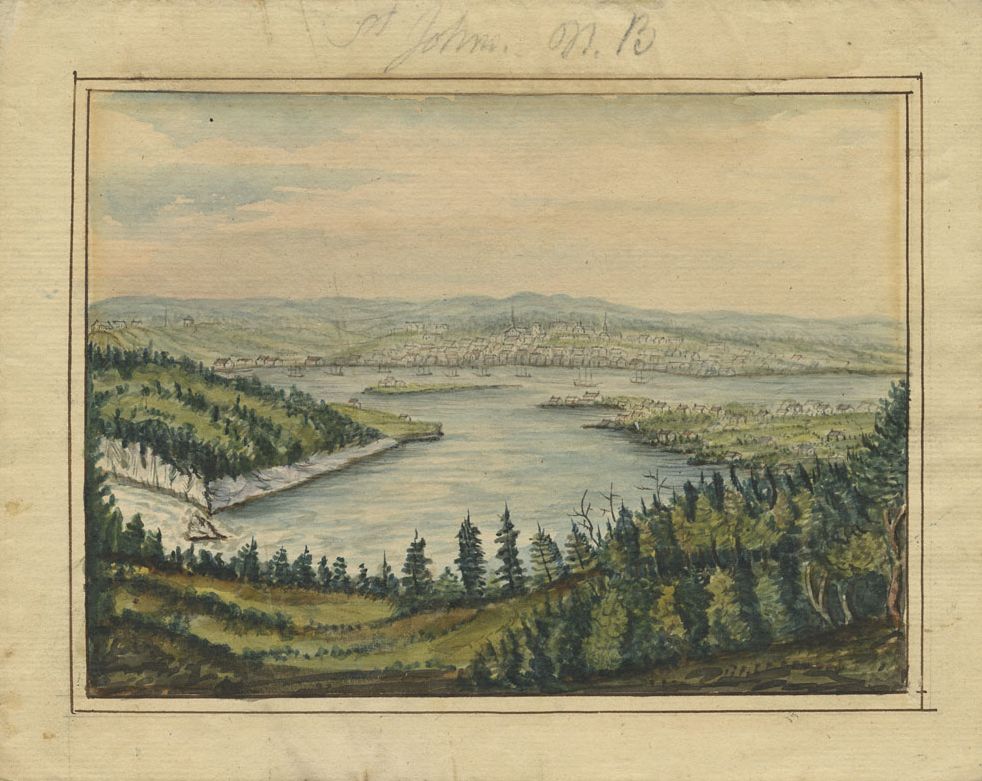

Located on the Bay of Fundy in New Brunswick, Canada, Saint John (or Parrtown, historically) was the first English incorporated city in what would later become the Maritime Provinces in Atlantic Canada. However, Indigenous communities such as the Wolastoquey (Maliseet) and the Mi’kmaq have traditionally inhabited the Saint John River Valley, along with the Passamquoddy in the Bay of Fundy area, for centuries; long before the British and French empires established colonial settlements in New Brunswick. The city’s Charter of Incorporation, submitted on April 30, 1785, two years after the landing of the Loyalists, was supposedly a testament to the inhabitants’ “exertions” in “conqueror[ing] many of the difficulties attending settlement of a new country.”

What the 1785 charter does not explicitly state, however, is that the Loyalist inhabitants mentioned above were white colonials. Under the charter, Black Loyalists who settled in New Brunswick were precluded from selling goods, practicing a skilled trade within the city limits, or fishing in the Saint John Harbour. The passages which directly relate to the disenfranchisement of people of colour begin (my bolding and italics throughout):

no person or persons shall be made free as aforesaid but such as are shall be natural born subjects of Us, our Heirs or Successors, or shall be naturalized or made Denizens. And We do further, for Us, our Heirs and Successors, ordain, appoint, direct, will and grant unto the American and European white inhabitants of the said city our loving subjects, who on the day of the date of these our letters patent are residents of the said city, that they may be admitted, and they are by these presents admitted free citizens of the said city, and shall be entitled to all the liberties, privileges and pre-eminences of freemen of the said city and of the liberties thereof . . .

This passage reveals the solidification of white Loyalists' domination in colonial New Brunswick society through their endeavor to establish the city of Saint John as a “white citizen zone,” thereby excluding people of colour from fully participating in Saint John’s economy. Black Loyalists were not necessarily physically prevented from residing within the city limits, as illustrated by Moses Simpson's land grant in the city centre. In 1785, he received lot 443 on George Street; however, within two years, Simpson, along with other Black Loyalists petitioned for land in Milkish Creek, Kings County. His departure from Saint John could have been prompted by the exclusionary atmosphere and/or lack of independant economic opportunity.

In conjunction with the poor quality of land that Black Loyalists received, this prohibition from selling what little produce Black communities could grow on their unfertile and marshy land plots, such as at Milkish Creek, would have been a significant financial loss. In 1795, ten years after the charter was ratified, Black individuals petitioned the city council for fishing rights but were ultimately unsuccessful in their fight for equal economic oppourtunities. Restrictions on fishing rights in the Saint John Harbour for people of colour remained in place up until the mid-nineteenth century.

As Saint John was the first city to receive a Royal Charter in the colonial Maritime Provinces, the 1785 document can be considered one of earliest acts of institutional discrimination against Black individuals in Atlantic Canada. The Saint John Charter was based upon the 1686 Dongan Charter of the Province of New York, which officially incorporated New York as a city. However, legislative and social discrimination against Indigenous communities (scalping proclamations against the Mi’kmaq, for example) predated the landing of the Loyalists by decades. African slavery was practiced at an earlier period in Nova Scotia by New England planters, but no legislation supporting the institution of slavery was ever enacted. Although the Royal Charter of Saint John is significant owing to its official status, pervasive racism which economically and socially deprived people of colour from fully and independently participating in occupational and political enterprises, was present long before Saint John’s legislation was ratified in 1785 with the institution of slavery.

In 1797, a Black Loyalist named Peter Thomson was issued a license to operate a tavern in Saint John. Thomson was formerly enslaved to Charles McPherson but was manumitted (released from slavery) for the amount of thirty pounds (or $4,590 in current US dollars). It is plausible that McPherson backed Thomas both socially and financially in order for Thomson to receive his tavern license, as no other occupational license was issued to a Black Loyalist in Saint John during this time. This license was not equitable with free citizenship, however, and was only permitted on rare occasions. After Thomson’s death in 1820, McPherson was recorded as one of the administrators of Thomson’s estate.

The Saint John charter reinforced the second-class citizen status of Black individuals in early New Brunswick society through segregation and the establishment of a dominant “white citizen zone” in Saint John. The presence of people of colour was only permitted in the occupational categories of either a labourer or servant: both of which were low socio-economic positions that did not allow an independent life free from white exploitation.

Sources Used

David Bell, Loyalist rebellion in New Brunswick: a defining conflict for Canada's political culture, Halifax: Formac Publishing Company Limited, 2013.

W. A. Spray, The Blacks in New Brunswick, [Fredericton, N.B.]: Brunswick Press, 1972.

Eric Teed, Saint John (N.B.), Canada's first city, Saint John: the Charter of 1785 and Common Council proceedings under Mayor G.G. Ludlow, 1785-1795, [Saint John, N.B.]: [publisher not identified], 1962.

Zoe Louise Jackson is a student assistant for the Microforms Unit at the Harriet Irving Library. She is currently in her final year of her Bachelor of Arts degree at UNB in Honours History.

Comments Add comment

Errors in article

Comments

We have made some clarifications to this blog post thank to a reader’s comments. We always invite constructive criticism and discussion! You may contact us at mic@unb.ca.

Why is it important for us to know about this

Add new comment Comments