- Submitted on

- 1 comment

Following from last week’s post, you will find in this entry a listing of practical “Tricks” to help in identifying surnames in primary documents, as well as a collection of resources which will aid in this undertaking.

Top Tricks

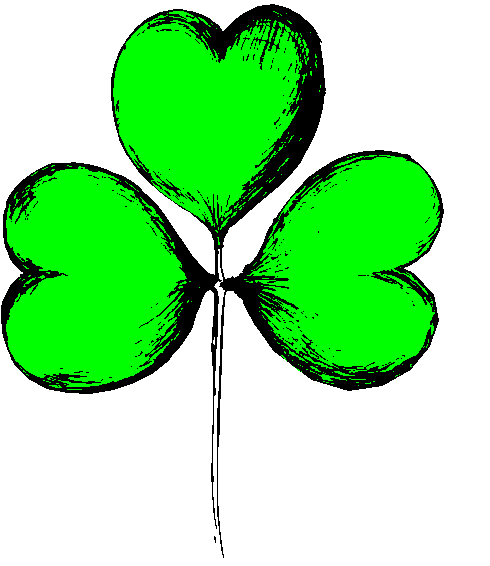

1. It is useful to browse databases that offer alphabetical lists of last names to locate variations in spellings. The program “Soundex”, used on sites such as the Provincial Archives of New Brunswick, is also helpful for last names that may not be clear or of variable spelling.

2. Say the name out loud to try to interpret phonetic spellings; this technique is particular helpful for non-anglophone names recorded by anglophones.

3. Try a comparison of accompanying information such as birth dates, locations, middle names, spouse, and children between two documents to determine if they are referring to the same individual. For example, “Elizabeth M. Smythe” born in 1821, Queensbury as likely the same as “Eliz. Mary Smith” born in 1821, Queensbury).

4. Use a local phone book to see if the surname in question is still popular in the area.

5. Employ secondary source indexes, either printed (e.g. The Loyalists of New Brunswick by Esther Clark Wright) or online (e.g. Nova Scotia Land Papers 1765-1800 by the Nova Scotia Archives).

Open Clip Art Library,

public domain)

Resources by Ethnicity for Surnames of the Maritime Provinces

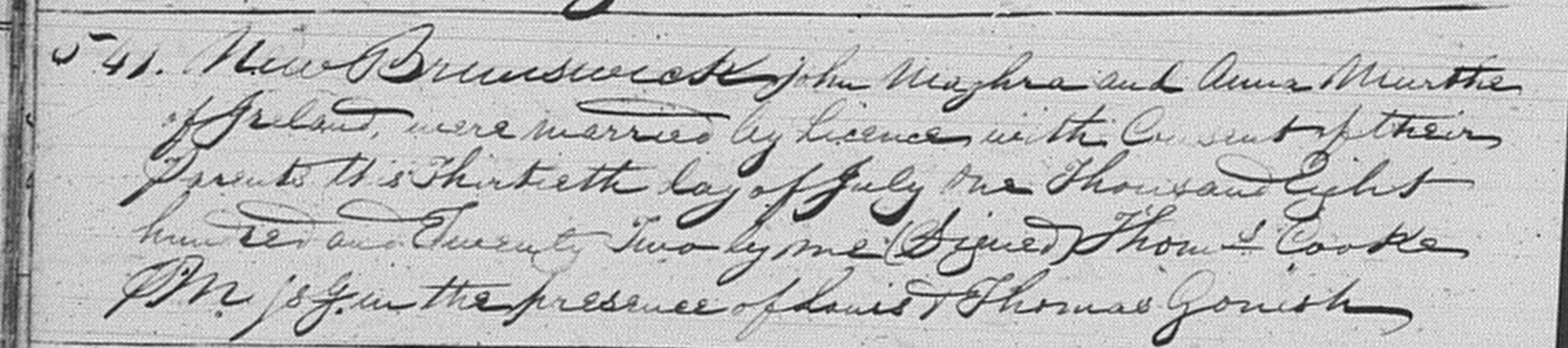

For French Acadian names: L’Acadie des Ancȇtres and Histoire et Généalogie des Acadiens (multiple volumes), both by Bona Arsenault. See also Acadian.org to browse surnames. An Acadian Parish Remembered, The Registers of St. Jean-Baptiste, Annapolis Royal, 1702-1755 on the Nova Scotia Archives website also offers a list of Acadian surnames and variations.

public domain)

For Irish names: see the multiple databases found in the Irish Portal on the Provincial Archives of New Brunswick site, particularly “Irish Immigrants in the New Brunswick Census of 1851 and 1861” for Irish surnames found in New Brunswick. Special Report on Surnames in Ireland by Robert E. Matheson (first published in 1901) gives good details on how last and first names were often written phonetically and anglicized in Ireland, as well as use of English translations of Irish Gaelic names. example, the phonetic spelling of “Cohoun” for the last name “Colquhoun.” A case of an Anglicized spelling of an Irish Gaelic surname is “Duggan” for “Ó Dubhágain”, and an English translation would be the last name of “Black” substituted for “Duff” from the Irish dubh meaning black. Erin’s Sons: Irish Arrivals in Atlantic Canada by Terrence Punch and Irish Families: Their Names, Arms and Origins and More Irish Families by Edward MacLysaght are also useful resources.

of the Mi'kmaq Nation.

By Himasaram (Own work)

[Public domain],

via Wikimedia Commons

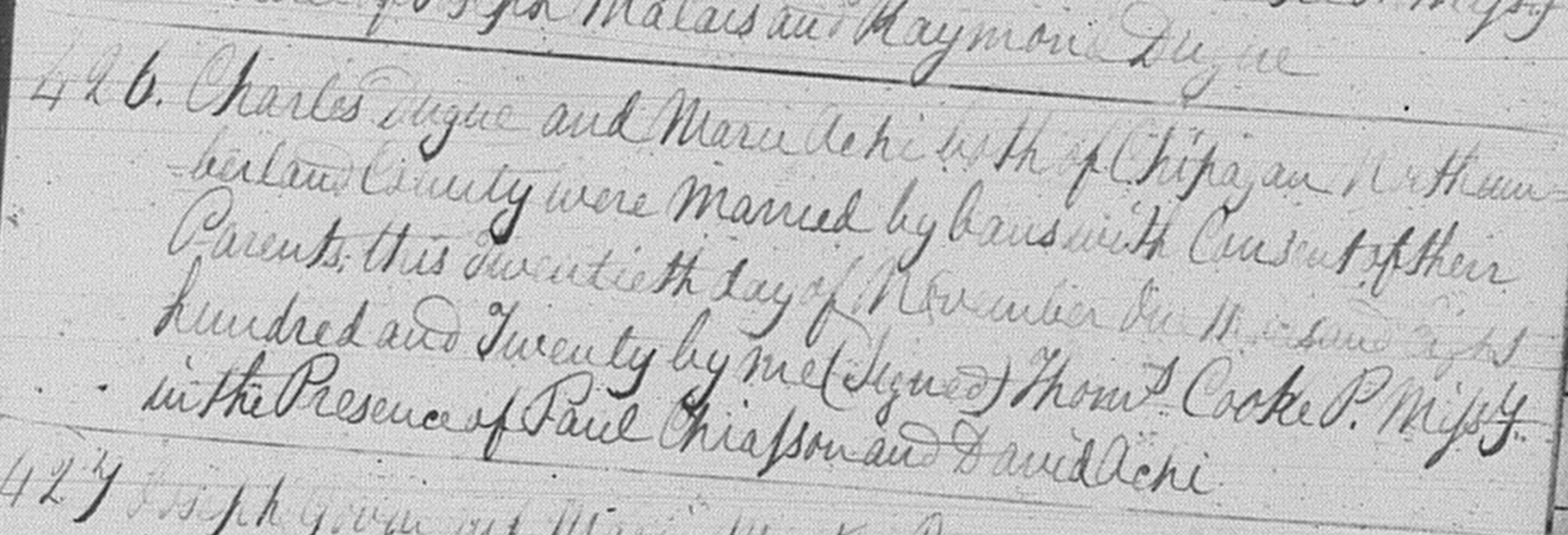

For First Nation names: Maliseet & Micmac Vital Statistics from New Brunswick Church Records by the Micmac-Maliseet Institute (now the Mi'kmaq-Wolastoqey Centre where the document is available online under "Resources"). Note that in this work, variants of last names are listed under one name (e.g. “Gonish” is under “Ginnish”). See also Aboriginal Entries: New Brunswick Census by the Micmac-Maliseet Institute with volumes for the years 1851, 1861, 1871, 1881, and 1891. The Nova Scotia Archives also offers a webpage entitled Advice for Researching Mi'kmaq Surname Variations.

For Scottish names: Scots Kith & Kin: A Comprehensive A-Z Guide to the Surnames of Scotland, the Clans and Their Tartans by Clan House of Edinburgh will give you a good start. Useful indexes are also found on the New Brunswick Scottish History site.

For Dutch names: The website “On the Trail of Our Ancestors” gives a good introduction to Dutch surnames in America.

For African Canadian names: The Book of Negroes is available on several sites for locating Black Loyalist surnames; note that a surname was not included for a large number of individuals. A list of black refugees from the War of 1812 arriving in Halifax can also be found on the Nova Scotia Archives site.

Although the lack of standardization of surnames can by trying for the researcher, the evolution and variations in spellings can actually be useful and interesting tools in themselves for the investigation of family history or to delve into the society in which the research subject was inhabiting.

Leah Grandy holds a PhD in History and works as a Microforms Assistant at the Harriet Irving Library.

Comments Add comment

thanks

Add new comment Comments