Who is That?!—Part 2: Help With Eighteenth and Nineteenth Century Surnames

As a continuation to the last post, Who is That?!: Help with Eighteenth and Nineteenth Century Given Names, here are some “Tips” to assist in the interpretation of last names with a focus on Maritime Canadian resources, although many of the following suggestions are applicable elsewhere.

Top Tips

1. It is most important not to get hung up on a certain spelling of a surname! A huge variety in spellings of names existed in eighteenth and nineteenth centuries. For instance, if a name is written “Havens” and you were looking for “Haven”, you should certainly not automatically discount this record. Coolen, Coolin, Coolan, Cooling, Coulin, Coulen, and Coolahan are all variations of the same surname found in Nova Scotian documentation. It is useful to compile a list of all the variations you have found of the surname which you are researching and look up each version when you utilize a new resource.

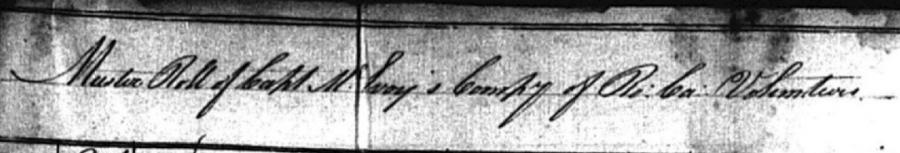

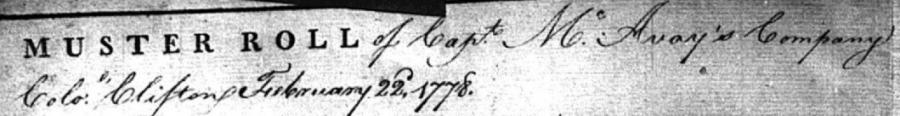

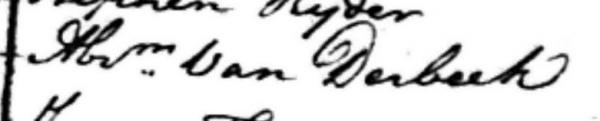

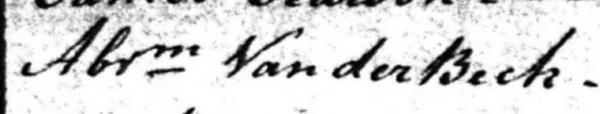

(Library and Archives Canada. British Military and Naval Records, “C Series”: 1767-1899, volume 1900)

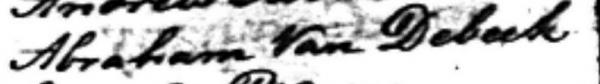

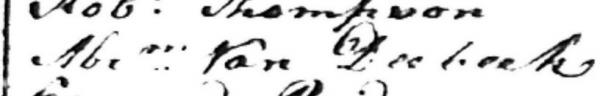

2. Names of Irish, French, and German origin were especially prone to variation due to anglophone recorders; for example, the Irish Dougherty became Dockarty, and the Acadian Breau turned into Bro. In the following example, the New Jersey Dutch name “Vanderbeck” appears as Vanderbeek, Van Der Beck, Van Deerbeak, AND Van Deerbeck within the same time period!

3. In Gaelic patronymics, “O’” is used for some Irish surnames, but is also easily dropped. For example, O’Donahue could also be written for the same family as simply Donahue. As well, Mac, Mc, and M’ could be used alternately, dropped, or changed over time in recordings, and frequently were.

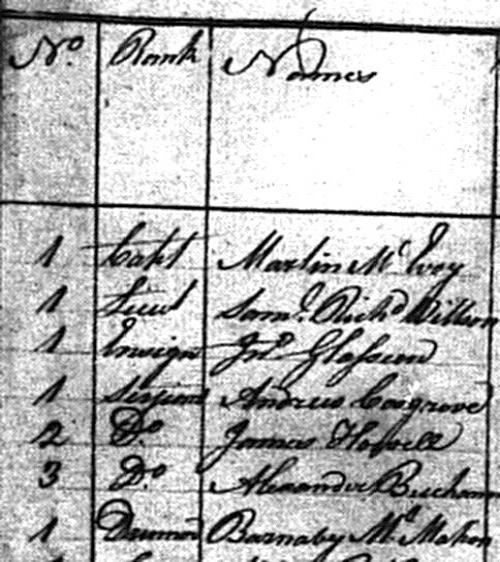

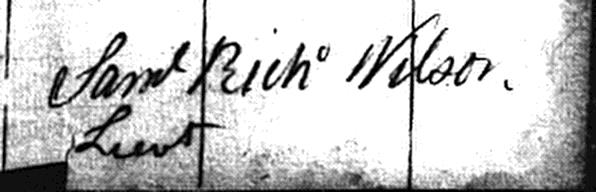

4. Names were often recorded differently within the very same document, demonstrating the recording of an accurate surname spelling was often of no great importance.

(Library and Archives Canada. British Military and Naval Records, “C Series”: 1767-1899, volume 1900)

5. Doubling or singling of consonants with a surname was very common (example: Esson could be the same name as Eson); “y” and “ie” were used interchangeably (as in Fahie/ Fahey); and an additional “e” was often placed on the end of a name (Sharp/ Sharpe).

Stay tuned next week for “Top Tricks” and resources to use in surname identification.

Leah Grandy holds a PhD in History and works as a Microforms Assistant at the Harriet Irving Library.

SUBJECTS: research skills, naming, language, genealogy

Add new comment