- Submitted on

- 0 comments

Dorcas, Nehemiah, Mehetabel, Eliphalet . . . If you have done any research with early North American documents, you have probably noticed that some names were fairly common in the past that are certainly not common today. This change over time in naming traditions may leave the modern reader puzzled. There are, however, some background knowledge and tricks that will help in the interpretation of early Canadian and American given names.

via Wikimedia Commons

The most common source of North American colonial names arrived via Christian traditions, particularly the Bible and saints. Interestingly, many Biblical names were not well known, and of no special importance. Some even had negative connotations such as Cain and Benoni. Strict American Protestants tended to prefer Old Testament names, while Catholics, especially French Catholics, held a tradition of choosing names from non-Biblical Saints. The appearance of some very obscure Biblical names such as Zalmon and Hilkiah may indicate that colonial parents may have been using the Bible in the same way as baby name books are used by modern parents.

Naming Trends

Colonial North Americans were not immune to the pull of “high”cultural movements and trends arising in Europe including Romanticism, Neoclassiciam, and popular literature. Examples of these “trendy” names include Archelaus, Lucretia, Semphronia, and Tristram.

and Ireland made “George” a popular

name during his reign and that of his

son, George IV. (by Allan Ramsay,

Public domain, via Wikimedia Commons)

Another trend found in naming practices was the rise in popularity of second names. In colonial North America, last names were often chosen for middle names for both males and females. Using last names as first names for males was quite popular as well (and was occasionally seen with females), so do not discount that possibility when trying to interpret a name; last names as first names were often chosen as a tribute to a particular family, especially a mother’s family.

The use of traditionally New England Puritan “grace” names such as Thankful, Patience, and Obedience for females and Asure, Justice, and Marvel for males was found on the Eastern Seaboard into the nineteenth century. Female names more commonly than male were often illustrative of religious virtues, such as Old Testament selections based on stories related to the bearer.

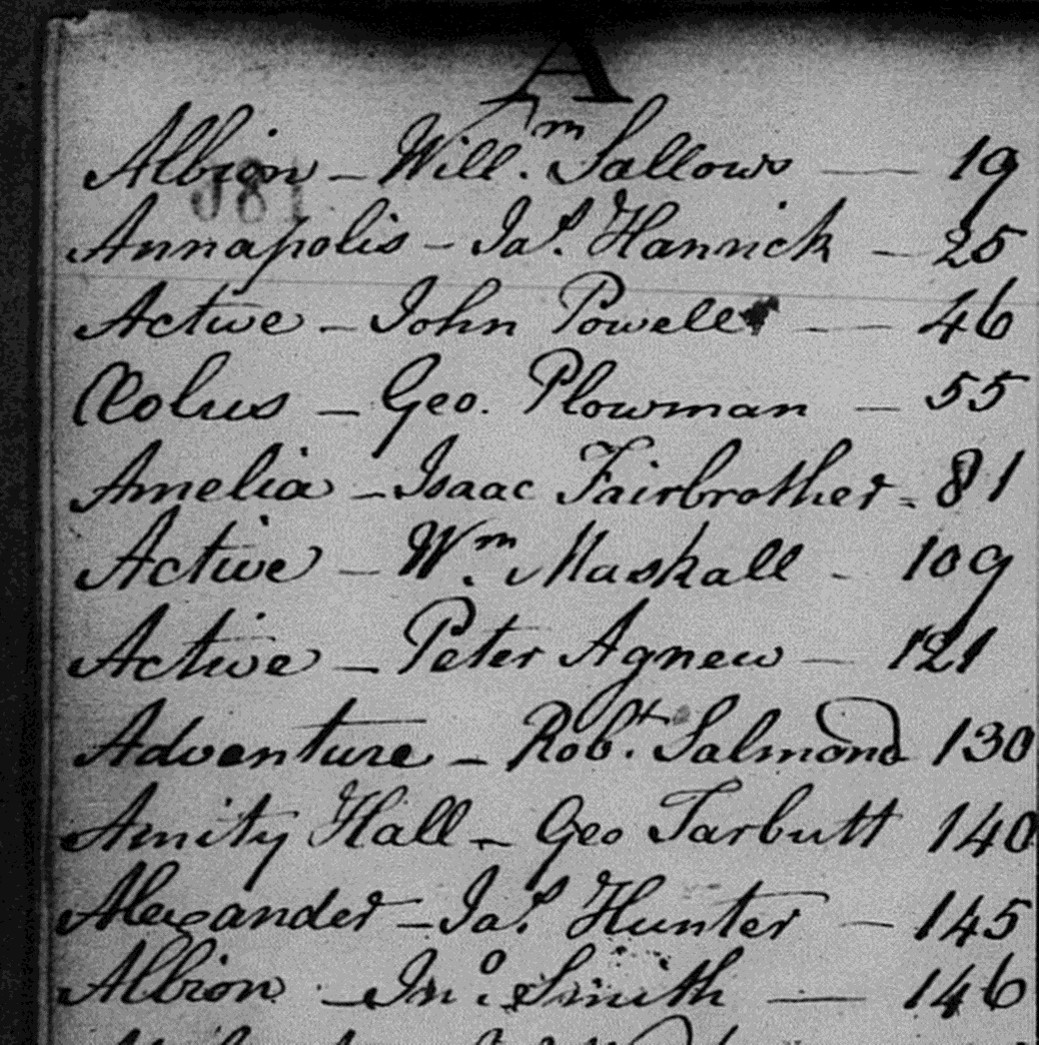

Children were also given names of prominent figures of the day, such as the notable number of Horatios, Nelsons, and Wellingtons in the early nineteenth century British colonies, and a high number of Georges in 1820, the year King George III of England died and was succeeded by George IV. Names used by European monarchs such as Charlotte, Caroline, Sophia, Edward, Henry, and Louis were also favourites.

In Acadian areas, French language versions of obscure saints were popular such as Ambroise, Hilarion, Apollina, and Scolastica. Both French and English language versions of names may appear in records for the same individual (such as Stephen and Etienne, Margaret and Margurite) because, in many regions of North America, anglophone clerks often recorded the English version; therefore, it is difficult to determine which name a person went by on a daily basis. Double names—particularly Jean Baptiste for males and combinations using Marie for females—were often chosen in Acadian communities.

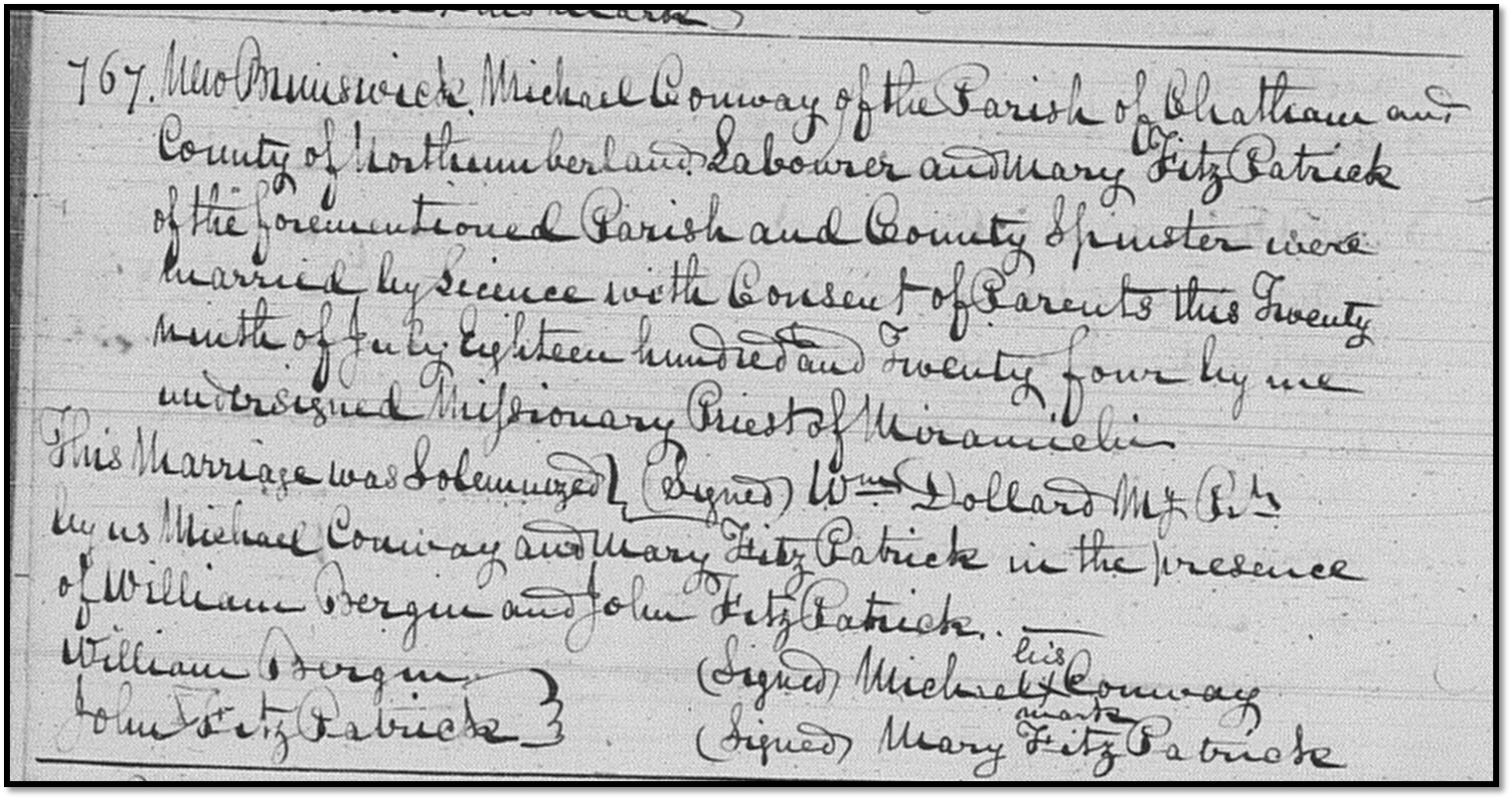

Among Irish immigrants and those of Irish descent, the names Patrick, Michael, Ellen, and Bridget appear in much higher frequency then the rest of the population.

Top Tips

It is important to note that older, and often phonetic spellings were often used, particularly in the eighteenth century, such as Phebe (Phoebe), Nansey (Nancy), Barbary (Barbara), Sharlotte (Charlotte), and Elexander (Alexander).

Some names, or spelling of names, may be very particular to a certain region, county, or community. For example, Diadama is a female name created in New England and transferred to New Brunswick.

Nicknames for men were rarely recorded in these formal records; for example, if a name is written as “Josh”, it is short for Joshua, not a nickname. Women’s nicknames were, however, regularly recorded such as Peggy (Margaret), Betsey/ Betty (Elizabeth), Polly/ Molly (Mary), Sally (Sarah), Fanny (Frances), Jenny (Jeanett/ Genvieve), and Nancy (Anne). Abbreviations for names were often common across documents and North America.

Top Tricks

If you are unsure of a first name because of the handwriting or it appears to be an usual name, a good approach to use is to check your best guess in a reputable name book, such as the American Given Names by George R. Stewart, which has accurate coverage of names in use in North America in the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries. If the name cannot be found in a reference book, try Googling the word using “first name [insert given name]” to see what you can discover and to determine if it is a plausible given name. The website Behind the Name website is also a useful tool.

Keep in mind unique names and last names as first names can be the hardest to verify; most names will fall in a small, common pool and will be easily recognizable unless handwriting is very sloppy. With experience, you will soon become an expert at identifying names common to your research area!

Leah Grandy holds a PhD in History and works as a Microforms Assistant at the Harriet Irving Library.

Add new comment