- Submitted on

- 0 comments

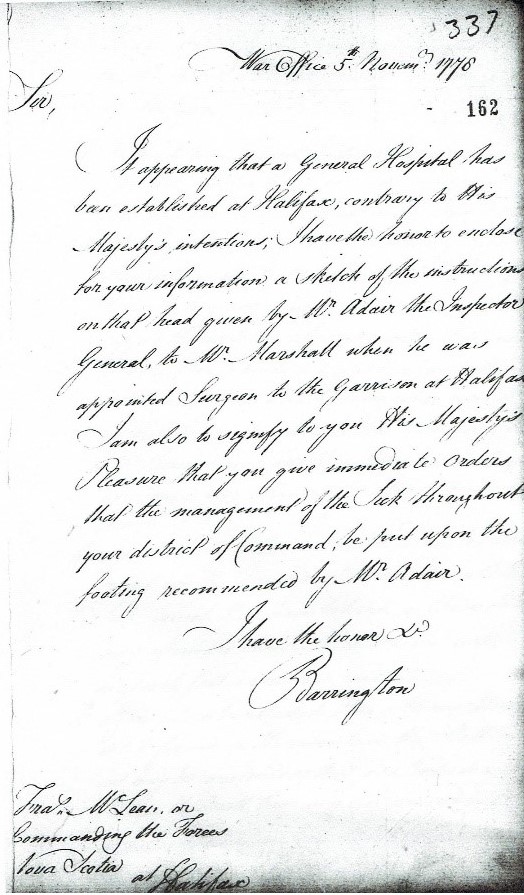

Newly promoted Brigadier General Francis MacLean could not have been pleased when he read the letter from Lord Barrington. William Wildman Shute Barrington, the second Viscount Barrington, was the Secretary at War for the British Government in London, and MacLean had been the commander of the British forces in Halifax for just a few months, having replaced General Eyre Massey after his arrival in August 1778.

The letter, in formal eighteenth-century language, takes MacLean to task for acting “contrary to His Majesty’s intentions” by permitting the ongoing functioning of a general hospital in Halifax. Barrington helpfully attached a detailed set of instructions about how to set things right. So, what prompted the reprimand?

Halifax, 1778

Halifax was a hub of activity in the late 1770s. The American Revolutionary War (1775-1783) was raging and proximity to America made the young harbor town an attractive garrison location for British forces.

British forces were regularly sent from England to defend the town as there was a real threat of invasion by the rebel forces to the south, and on 12 August 1778 three Regiments, under MacLean’s command, arrived to fortify the garrison.

The forces brought with them the staff and supplies required to establish a “hospital.” Some 50 tons of supplies, a head surgeon (Dr. John Marshall), three surgeons’ mates (assistants) and an apothecary (think pharmacist). Their orders were to establish a “Garrison Establishment” (military hospital) and specifically not a general hospital - but that apparently was not what happened.

The Eighteenth-Century “Hospital”

It must be understood that in 1778 the term “hospital” did not mean what it implies today. The 1778 general hospital was not defined by a fixed structure, but rather by its medical staff. It existed alongside the more common Regimental Hospital – which as the name suggests provided care at the regimental level (600-800 men). The general hospital usually had a larger and often more skilled medical staff and was therefore more expensive to operate. It also accepted a more varied population of patients, not just those of a single regiment. Regimental Hospitals were perceived as superior for several reasons, as explained in the attachment to Barrington’s letter. They were cheaper to operate, they dispersed the troops and made them less susceptible to contagion, and the men were better cared for under their own surgeon with the result that their “care was more regular in conduct.”

Halifax was served by a General Military Hospital located on the south side of Blowers Street, immediately across from where Argyle Street joins. The General Military Hospital, as the name suggests, served everybody and was created in 1758 and closed in 1797. It was the ongoing management of the General Military Hospital that was the focus of Lord Barrington’s concern. In 1778, when MacLean and Dr. Marshall arrived, the general hospital was under the direction of Dr. John Jeffries.

(by Fulgence Marion, pseudonym of Camille Flamarrion, Public Domain via Wikimedia Commons)

Dr. John Jeffries

Dr. John Jeffries fled Boston in March 1776 with Howe’s army and set up practice in Halifax. He was a graduate of Harvard and received his medical training at the University of Aberdeen. This represented exceptional medical qualification for the time. He also had military medicine experience having served the Royal Navy at Boston and treated the wounded from the battles at Lexington and Bunker Hill. Following arrival in Halifax, under orders from Massey, he became the purveyor (administrator) of the hospital on Blowers Street. Dr. Marshall’s arrival in August of 1778 should have seen the operation of the Blowers Street location as a general hospital cease and the creation of Regimental Hospitals in its place. The original orders seem clear, Jeffries’ Orderly Book entry on August 21st, 1778 records the newly arrived staff under Dr. Marshall and states: “Its therefore General Massey’s orders they take the [general] [hospital] into charge and be [obeyed] as the staff of this garrison.”

It is through Jeffries’ personal diary and Military Orderly Book (copies of which are held in The Loyalist Collection) that the events leading up to MacLean’s reprimand can be better understood.

A Difficult Situation

The General Military Hospital on Blowers Street wasn’t the only one on that street. There was also a jail housing American patriot prisoners that had a section functioning as a hospital. It was needed in order to treat the captives who got sick and died with some regularity. Jeffries writing suggests the two hospitals were almost contiguous. This was a problem because a population of frequently diseased men were being housed next to the general hospital and Dr. Jeffries had permission to admit the sick rebels to the general hospital, under guard, whenever he saw fit! The guard were under orders “to put to death any rebel that dares to run off”. The smallpox situation was so bad that the Town Major (a position established for garrison towns) was ordered to ensure that only soldiers who had survived the disease (and were thus immune) formed the guard unit at the jail.

Conditions at the jail were bad enough that Dr. Marshall was moved to complain up the chain of command. He wrote to Robert Adair, the Inspector General of Regimental Infirmaries that “herrings salted up in casks best convey some idea of the situation of the prisoners. Deaths are extremely frequent…” The situation was discussed at cabinet level in the British government, and with realization that orders had not been followed, the reprimand was quickly issued.

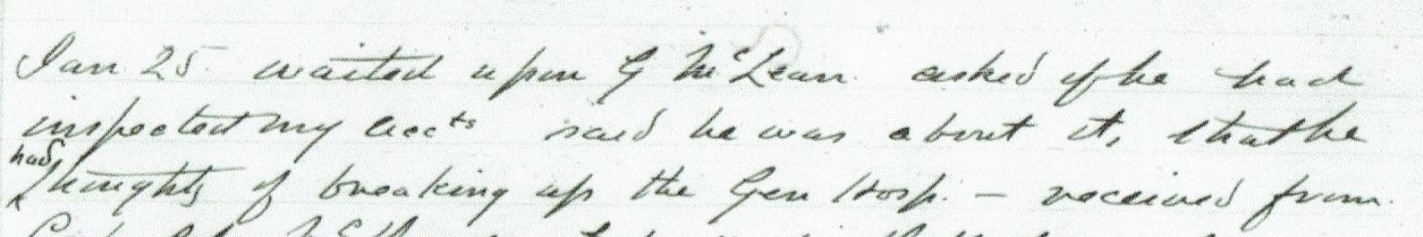

MacLean’s reaction was also swift. One can surmise that Barrington’s letter arrived by mid-January 1779 because Jeffries recorded in his diary on the 25th the following account of a conversation with General MacLean: “…he had thoughts of breaking up the Gen [general] Hosp [hospital] . . . ”

(John Jeffries Papers: 1775-1835, The Loyalist Collection, originals Massachusetts Historical Society)

Conclusions

Knowing the details of the events that occurred to prompt MacLean’s reprimand, it is tempting to speculate as to how the situation arose. Did MacLean deliberately disobey orders or is there another explanation?

Jeffries’ diary entry for August 22nd records that “In the Eve Mr. Marshall, surgeon of the Genl [general] Hospital first visited the Hospital . . .” Given the recorded arrival of MacLean on August 12th, was there a reluctance on the part of Marshall to involve himself in the general hospital’s affairs? He had acted rapidly to make his concerns about the state of the rebel hospital known. The fact that between his arrival in mid-August 1778 and early November, by which time those concerns had made their way to London and policy formulated, suggest he acted quickly indeed.

But why didn’t he just use his command authority and close the general hospital as he had clear orders to do? The answer may lie in his relationship with Dr. Jeffries. Jeffries, at Halifax in 1778, was an experienced, well-qualified physician. He had been in command of both military and civilian medical affairs for two years. In contrast, while much biographical detail may be readily discovered about Jeffries; Marshall remains an unknown figure. A search of typical sources for biographical data has turned up nothing about his medical qualifications or prior experience. Perhaps Marshall was reluctant to exert authority over a physician who he felt was his superior in knowledge and experience.

Finally, with respect to General MacLean, the events leading to the reprimand occurred within two months of his arrival at Halifax garrison; which was his first such command. It is hardly surprising that he may well have assigned lower priority to the matter of the hospital, involved as he was in a very active and fluid military situation in a theatre of war. His reprimand was therefore nothing more than a response to a simple oversight on his part.

Stephen Bolton is an auditing student of the Revolutionary and Loyalist Era Medicine course at UNB’s History Department. He holds a PhD (Chemistry) from the University of New Brunswick and an MD from Dalhousie University. He is a historical re-enactor of the Revolutionary War period, serving with Delancey’s Brigade (a Loyalist Provincial Corps unit).

![]()

Secondary Sources Used

“BARRINGTON, William Wildman, 2nd Visct. Barrington [I] (1717-93), of Beckett, Berks,” The History of Parliament: British Political, Social, and Local History Website.

Paul E. Kopperman, “Medical Services in the British Army, 1742-1783,” Journal of the History of Medicine, (October 1978).

A. E. Marble, Surgeons, Smallpox and the Poor: A History of Medicine and Social Conditions in Nova Scotia, 1749-1799, (McGill-Queen's University Press: Montreal, Que., 1993).

Franklin B. Wickwire,“McLEAN, FRANCIS,” Dictionary of Canadian Biography Website.

Add new comment