- Submitted on

- 6 comments

In the early nineteenth century, two fatal duels took place in the Maritimes: one in Nova Scotia and the other in New Brunswick. These duels happened between prominent members of society and were fought with pistols. Despite duels being illegal, they still happened, and like the cases that will be discussed in this post, they occurred as a result of bruised egos and served to defend personal honour. Duels were found amongst the first generation of loyalists as they were trying to establish themselves and their status in their newly formed societies. However, by the turn of the nineteenth century, duels were less commonplace—especially after the Uniacke duel.

(By Rama, own work, via Wikimedia Commons)

The Uniacke duel and resulting trial served as the example to argue against and condemn duels. This pivotal duel took place in Nova Scotia in 1819 where Richard John Uniacke Jr. defeated William Bowie resulting in his death. This created a public outcry against duels in both Nova Scotia and in the neighbouring province of New Brunswick. In 1821 another fatal duel occurred; this occurred in New Brunswick when, during a legal trial, George Ludlow Wetmore and George Frederick Street had an argument that was carried outside of the courtroom—eventually leading to a duel in which Street mortally shot Wetmore. This was the last fatal duel in New Brunswick—probably because this duel and resulting trial, in which Street was acquitted, resulted in even more public objection.

Nova Scotia Museum.

(Image courtesy of Wikimedia Commons. Public Domain)

Uniacke vs. Bowie

On July 21, 1819 Richard John Uniacke Jr. and William Bowie participated in the last duel in Nova Scotia. Bowie was a merchant and Uniacke was the son of the province’s attorney general. This duel, much like the Street and Wetmore duel, was about honour; Uniacke had insinuated a few days before that Bowie was a smuggler, and Bowie had asked for a retraction. When Uniacke refused to withdraw his comments, Bowie demanded a duel in order to preserve his good name. In a field outside the city of Halifax near what now is Lady Hammond Road, Uniacke killed Bowie and was later charged with murder. Uniacke’s second, Edward McSweeney, who were respectively the president and vice-president of the Charitable Irish Society of Halifax, was also charged and it was revealed that he was in debt to Bowie and had encouraged a second shot, which had proved mortal. At the trial, Uniacke’s father, attorney general Richard John Uniacke Sr., escorted his son into the courtroom. Not wanting to upset this powerful family, the jury found Uniacke not guilty.

(UNB Libraries Microform Newspaper Collection)

In an extensive article in the Saint John City Gazette, New Brunswick, about the details of this court case. Two doctors confirmed that the wound from the duel caused Bowie’s death. Interestingly, the article states that there were many witnesses who claimed that Bowie respected the outcome of the duel before his death and did not consider Uniacke his murderer. Uniacke went on to become a Member of the Legislative Assembly for Cape Breton one year after this event, and in 1830 he was also appointed to the Supreme Court. However, some have surmised that his early death at 44 years of age came as a result of the internal guilt revolving around this duel.

(UNB Libraries Microform Newspaper Collection)

Wetmore vs. Street

Another duel fueled by the desire to defend one’s honour was between George Ludlow Wetmore and George Frederick Street. G.L. Wetmore was the son of New Brunswick attorney general Thomas Wetmore, while G.F. Street’s father, Samuel Denny Street, was also a lawyer and had been involved in duels himself. The senior Street’s duel also came as a result of a court case with John Murray Bliss as his opponent, which was the earliest recorded duel in New Brunswick; however, in this duel, both participants missed their marks. The two young men came from social networks which were competing for political and administrative control of the emerging province of New Brunswick.

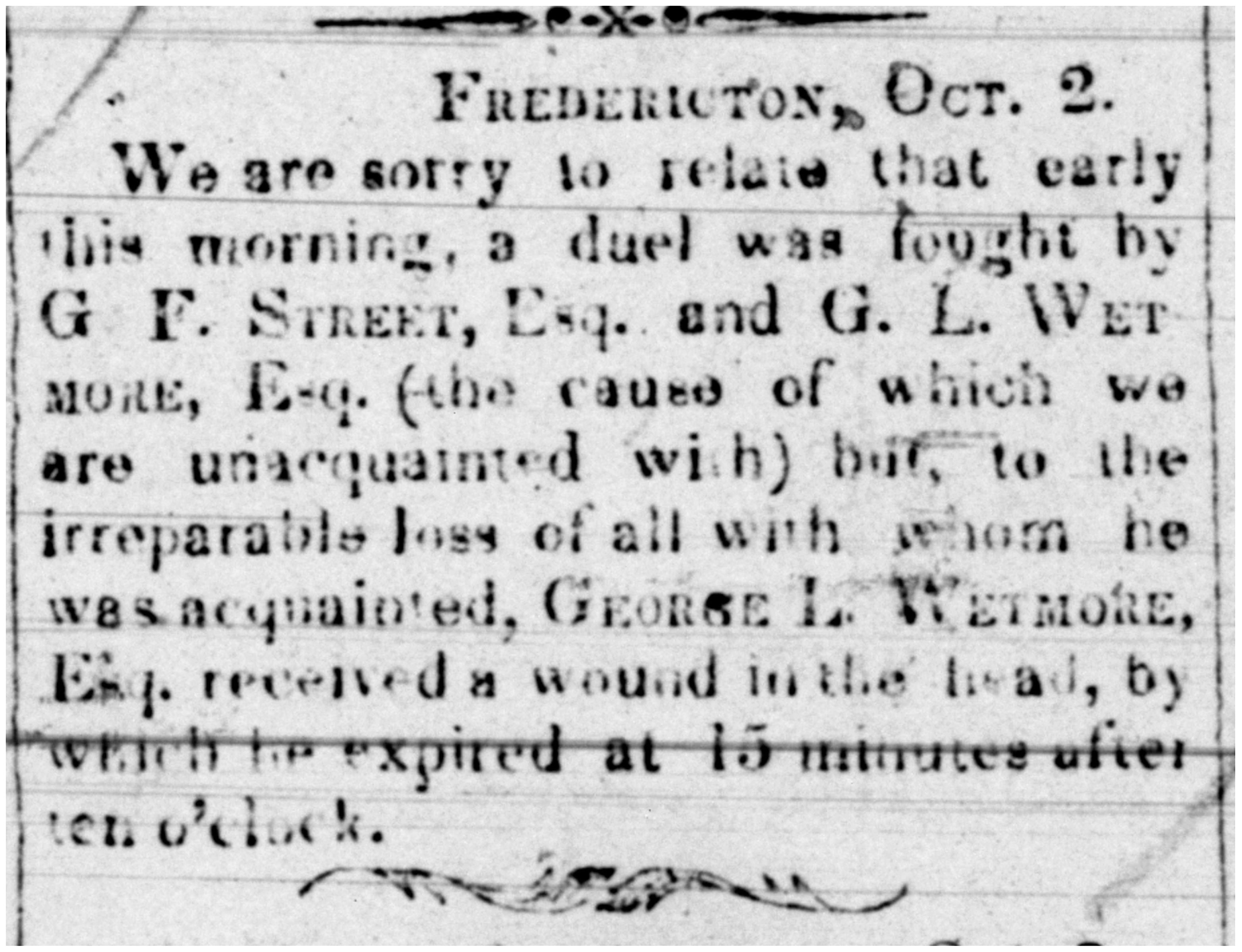

Wetmore and Street’s duel occurred in secret on the morning of October 2nd in 1821 on the Segee farm in New Maryland, York County, New Brunswick, then called Maryland Hill. Testimony from Street’s trial described a local witness’ experience, “Mr. Segee got up at his usual hour, and shortly after heard two pistols in quick succession, he could distinguish a difference in the report; about six or seven minutes after, heard two more; and soon after went to the place where the firing was heard, and found the deceased, with two wounds, one in the arm and one near the right temple; he was alive but insensible . . .” According to accounts of the duel, which may have been biased and prejudiced, both men shot their first round, but Street shot at the ground intentionally because he was willing to resolve the argument. Wetmore, however, demanded another round, and it would be a fatal one. Street’s bullet killed Wetmore—passing through his elbow and going into his head.

(UNB Libraries Microforms Newspaper Collection)

A warrant was obtained for Street’s arrest at the insistence of Wetmore’s friends, yet when brought to court in 1822, Street was acquitted. At Street’s trial for the murder of Wetmore and illegal dueling, as the Dictionary of Canadian Biography states, “one has the impression that the witnesses, the judges, and the prosecuting officers were united in a conspiracy to prevent the law against duelling from being enforced. These were, of course, the same men who enforced the criminal law with such vigour against those who were not members of the gentry.” Street went on to hold significant positions in New Brunswick circles, such as the treasurer-clerk for the College of New Brunswick and a Supreme Court Judge. He later expressed remorse for killing Wetmore, yet in 1834 he challenged Henry George Clopper to a duel—once more to defend his honour. On this occasion, however, Clopper dismissed the challenge. This was perhaps a sign that the ideologies behind dueling were changing in their society, and maybe Wetmore’s death had taught them an important lesson.

located in New Maryland, New Brunswick.

Even though duels were illegal, it did not stop their occurrence in the early nineteenth century. Both of the duels discussed ended in murder, yet both “killers” got off without any charges because of their elevated status in society. Had they killed their opponents in cold blood in a non-duel style, would this have been the case? Was dueling even an honourable way to resolve problems? It that as the nineteenth century progressed, duelling became less and less acceptable—which resulted in fewer duels, and its disappearance in the Maritimes.

Annabelle Babineau was a student assistant at the Harriet Irving Library. She is entering her first year of the English Masters Programme at UNB.

Comments Add comment

Segee Farm

Segee Farm

Thanks for your comment. In the research done for this piece, the documents did not indicate the first name of Mr. Segee who owned the farm at the time. In this time period, it was possible it was still in possession of the original loyalist or had been transferred to his sons. We have great resources to further your family history and potentially answer your question within The Loyalist Collection at the Harriet Irving Library, so please feel free to visit!

Segee Farm

We do offer limited research

We do offer limited research services, but you are absolutely right, the Provincial Archives of New Brunswick has a wonderful database of New Brunswick land documents (petitions and grants) available online.

Street vs. Wetmore Dual about 1821

Is there any record of the make of the pistols used?

Thank you.

Street vs. Wetmore Dual about 1821

Hello,

Not that we are aware of, but you may want to send a query to the Provincial Archives of New Brunswick as they may have more information.

Add new comment Comments