- Submitted on

- 2 comments

During the seventy years after the Loyalists arrived, New Brunswick and Nova Scotia remained a prosperous, albeit cold and unforgiving. When first settled, not only did Loyalist families have to cope with a drastic change in scenery and general quality of life, they also had to contend with the regret of what they had lost: thousands of casualties associated with the Revolutionary War, a slew of separated families, and £9 million in property losses, only £3 million of which was ever repaid by the Loyalist Claims Commission.

(From “Our greater country; being a standard history of the United States from the discovery of the American continent to the present time (1901).” Henry Davenport Northrop, 1901. Provided via Public Domain from Wikimedia Commons)

While in the American colonies, loyalists were prone to arrest, assault, robbery, and poverty; once in Canada, the lives of these dedicated loyalists and their descendants sometimes never improved. Due to the inherent economic struggles associated with the developing, colonial economy in New Brunswick and Nova Scotia, many new residents struggled to find meaningful employment and integrate themselves into the community.

Psychological turmoil, however, certainly did not end with the loyalist era. On the contrary, loyalist descendants and other immigrants still had to contend with dramatic shifts in climate, culture, agriculture, and industrial development. The War of 1812 also played no small role in the mental and emotional pain suffered by those living in the region.

This ultimate sense of despair was well documented within New Brunswick’s early newspapers, which Daniel F. Johnson neatly catalogued in his vital statistic database hosted on the Provincial Archives of New Brunswick’s website. Between 1784 and 1850, papers such as the New Brunswick Royal Gazette, the New Brunswick Courier, the Carleton Sentinel, and several others, reported numerous suicides within and around the New Brunswick area. These publicly announced suicides, along with other well-known examples including the case of Fyler Dibblee, make up a sample of 30 suicides reported by early New Brunswick newspapers.

In terms of occupation, military personnel, both during and after serving, died by suicide at a far higher rate than any other occupation. Out of the 30 suicides examined, 17 victims had some form of history in the military or local militias. That equates to 56.6% of the sample. Positions and ranks ranged from private and sergeant major to lieutenant and lieutenant colonel. Five of the subjects, or 16.6% of the sample, had no history in the military. Eight subjects, or 26.6%, had no identifiable occupation.

The data was starkly divided between the sexes, with men representing an overwhelming 84% of victims and women representing 16%. Of course, that is not to say women did not face hardship. Rather, women are instead more likely to resort to less violent and destructive suicide methods, making the likelihood of survival far higher. Modern studies regarding the subject have documented a well-established trend in which women tend to attempt suicide at a higher rate than men, while men die by suicide over three times more than women.

Yet, to truly gather any semblance of understanding, it is important to learn about the lives and stories of these victims in more detail. While statistics can be helpful, they rarely accurately depict the complicated situations and circumstances surrounding the individual cases that they represent. In order to combat that problem, this post will outline just a few of the many stories of those that suffered the mental, emotional, and psychological tolls of Maritime life during and in the half century after the Revolutionary War.

One of the more well-known cases documented in the sample was that of Fyler Dibblee. Fyler, born in 1741 in Stamford, Connecticut, was a university graduate and lawyer. While in Stamford, Fyler served as the leader of the town’s local militia and representative in the Connecticut General Assembly. In 1763, Fyler married Polly Jarvis Dibblee and the couple had five children across the next ten years of their marriage; Walter, William, Peggy, Ralph, and Sally. However, by the time the American Revolution came along, Fyler’s successes as a lawyer and father could only get him so far. A devout loyalist, Fyler and the rest of his family were soon labeled as traitors to the American people and successively attacked, robbed, and betrayed by the American state.

Some form of limited relief came once the family travelled to Saint John, New Brunswick. However, while free from Patriot attacks, the Dibblee’s were far from immune to the woes poverty. Unable to find stable employment, Fyler quickly racked up significant debt. Now dejected and destitute, Fyler fell into a deep depression, gripped by the anxiety and fears instilled in him by his time in the United States. According to his brother in law, William Jarvis, Fyler’s crushing depression soon became too much to bear: “whilst the Famely [sic] were at Tea, Mr. Dibblee walked back and forth in the Room, seemingly much composed: but unobserved he took a Razor from the Closet, threw himself on the bed, drew the Curtains, and cut his own Throat.” Fyler Dibblee died of suicide on May 6th, 1784.

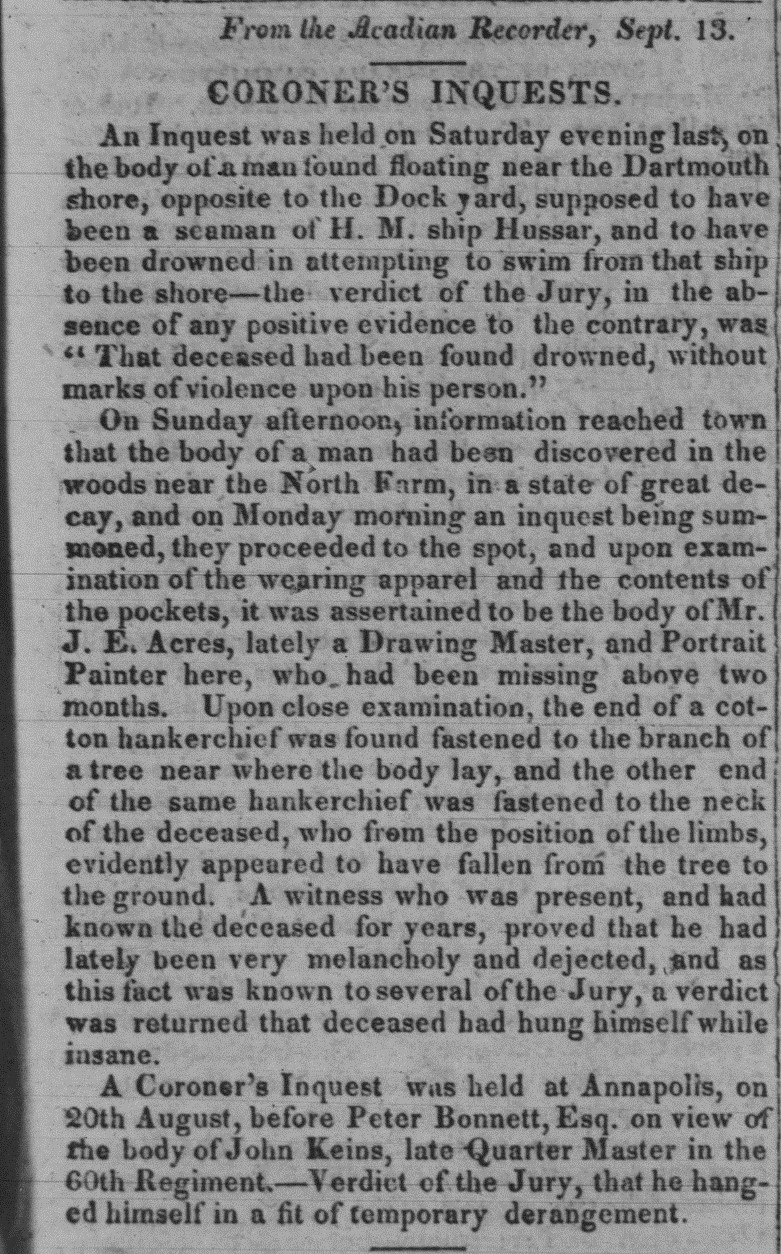

(UNB Libraries, Microform Newspaper Collection)

One notable victim included in the sample was John Edward Acres, often shortened to J.E. Acres. Acres was baptized on May 14, 1780 at St. Mary-at-Lambeth Parish in Surrey County England. He remained in London for around 35 years, where he studied art at the Royal Academy. In 1803, Acres married Sarah Sparrow, and in 1815, temporarily moved to Sydney, Cape Breton. In September of that year, Acres relocated to Halifax, where he worked as a renowned drawing-master and miniature painter. From 1817 to 1828, Acres travelled between Sydney and Halifax, working as a professional artist and teacher of “very considerable skill,” focusing primarily on miniature work. John Edward Acres died of suicide in 1828, as reported by The New Brunswick Royal Gazette.

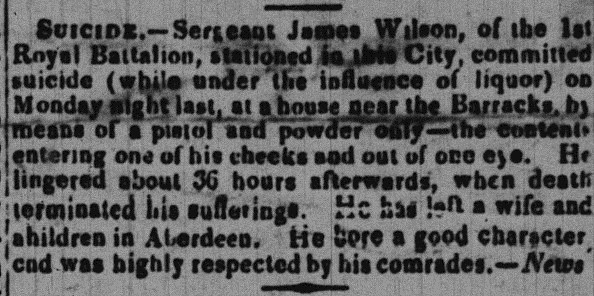

(UNB Libraries, Microform Newspaper Collection)

Another victim, a man named James Wilson, served as a Sergeant for the 1st Royal Battalion stationed in Saint John. Wilson died of suicide on Monday November 13, 1848 “while under the influence of liquor.” Wilson passed “by the means of a pistol and powder only - the contents entering one of his cheeks and out of one eye.” Sadly, Wilson suffered for another 36 hours after the event, at which point “death terminated his sufferings.”

Stories such as these were all too common in eighteenth- and nineteenth-century New Brunswick and Nova Scotia. For many new residents, the transition to life in the new colonies was altogether far too stressful and psychologically demanding. Entire families were ripped apart, relationships were broken, and friendships were crushed, but many endured, contributing to the mix of cultures now found in the Maritime Provinces.

Harrison Dressler is a second year Arts student at UNB and is currently working as a student assistant in Microforms, Archives & Special Collections.

Suggested Readings

Maya Jasanoff, "The Other Side of Revolution: Loyalists in the British Empire," The William and Mary Quarterly, Third Series, 65, no. 2 (2008): 205-32.

Comments Add comment

new book featuring Timothy Ruggles

Fyler & Polly Dibblee: children

Fyler & Polly had SIX children; the first 5 were baptized in Stamford CT; the 6th was Ebenezer [named for his grandfather]. Eben was born behind enemy lines on Long Island; he came to NB with his parents and five siblings on The Union. [He is my ancestor & I have "proven" to both Fyler & Polly thru' the UELAC; therefore have satisfied the Society that Eben was the youngest of the six children]

Thanks

Add new comment Comments