- Submitted on

- 0 comments

One of the first motions recorded in the Journal of the House of Assembly of the Province of New Brunswick was that of Mr. James Campbell, a representative for the County of Charlotte, who moved to bring in a bill to regulate servants. Although this bill, proposed on January 24th, 1786, was rejected by the vast majority, the push for such law early in the history of the province reveals the desire to legitimize the institution of slavery in New Brunswick.

The desire to legitimize the institution of slavery finds it origins with the Loyalist settlers, accompanied their “servants”, who arrived to British North America after the American Revolution. For clarification, servant and slave were interchangeable terms; in 1899, according to Methodist minister and early historian, T.W Smith, the title “servant” was a euphemism for a slave at this time and place, and even more so, asserted that most servants were actually slaves:

[S]till-enslaved Negroes brought by the Loyalist owners to the Maritime Provinces in 1783 and 1784 were classed as “servants” in some of the documents of the day. Lists of Loyalist companies bound for Shelburne, [Nova Scotia], made out, it is probable, under the direction of British officers whose dislike to the word “slave” would lead them to use the alternative legal terms, contain columns for “men, women, children and servants,” the figures in the “servants” column being altogether disproportionate to those in the preceding columns.

Fyler Dibblee is an example of a Loyalists who brought “servants” to the Maritimes. Dibblee was an

attorney-at-law from Stamford, Connecticut, who boarded the Union at Huntington Bay, New York in April 16th, 1783 and arrived at present-day St. John, New Brunswick May 11th, 1783. He was listed on the ship passenger list alongside his wife, Polly, three children over the age of ten, one child under the age of ten, and two servants – the only two servants on the ship and among the first Black Loyalists to arrive in New Brunswick.

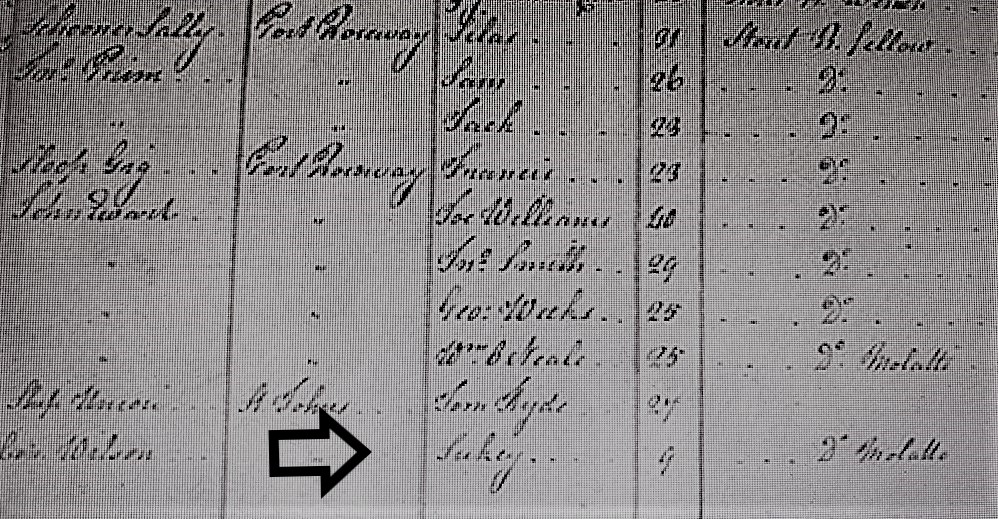

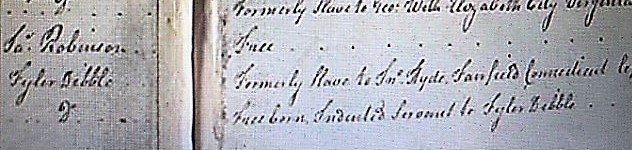

In the Book of Negroes – a list predominately made up of persons of colour that evacuated from New York between April to November 1783 – Tom Hyde, age 27 and Sukey, age 9, are listed as arriving in Saint John (or Parr Town) upon the Union and are named as Dibblee’s “possession”.

Tom Hyde, as written in the Book of Negroes, was formerly enslaved to John Hyde in Fairfield, Connecticut when he escaped to British lines and found employment with the Dibblee family. It is unclear as to whether Tom was enslaved to the Dibblees. Tom Hyde’s predicament is an example of what Thomas Peters – a black community leader, influential in settling black Canadians to Sierra Leone in West Africa – stated in his 1790 “humble petition.” Peters’s “humble petition” was to Lord Grenville, one of His Majesty’s principal Secretaries of State, in regards to free blacks who “have already been reduced to Slavery without being able to attain any redress from the King’s court”. Accordingly, to be a “free black” had very little meaning and the ambiguity between a person of colour and enslaved person reveals that loyalist New Brunswick was more concerned with race rather than one’s legal status.

As to the young girl, Sukey, in the Book of Negroes, she is described as being of mixed parentage and free born, yet an indentured servant to Dibblee.

Although the life stories of Tom Hyde and Sukey disappear shortly after Fyler Dibblee’s death on May 6th, 1784, it is safe to assume because of her husband’s death, Polly Dibblee released Hyde and Sukey due to her impoverished situation. Although Polly presumably released Tom and Sukey, the City of Saint John restricted Black persons. The Charter of the City of Saint John incorporated April 30th, 1785, placed severe restrictions on persons of colour and once again reinforced that one’s racial identity is a determinant factor rather than one’s status as to be free or not to be free.

Next Post: “Institutional Discrimination in the 1785 Saint John Royal Charter”

Sources Used

“Arrival of the Black Loyalists: Saint John’s Black Community: Heritage Resources Saint John,” Heritage Resources and New Brunswick Community College - Saint John.

Guy Carleton, 1st Baron Dorchester, “Book of Negros” in Papers, The National Archives, Kew (PRO 30/55/100) 10427 p. 1 African Nova Scotian in the Age of Slavery and Abolition.

Harvey Amani Whitfield, “Introduction: Slavery in the Maritime Colonies,” in North to Bondage: Loyalist Slavery in the Maritimes, (Vancouver, BC: The University of British Colombia, 2016), 16.

I.Allen Jack, “THE LOYALISTS AND SLAVERY IN NEW BRUNSWICK ST. JOHN, N.B (Communicated by Sir J. Bourinot, and read May 26, 1898) Transactions of the Royal Society of Canada, Second Series, Vol. IV, 1898-99, pp.137-185. Fort Havoc, Wallace Hale, comp. Provincial Archives of New Brunswick.

Lorenzo Sabine, “DIBBLEE, FYLER,” in Biographical Sketches of Loyalists of the American Revolution with an Historical Essay, (Boston: Charles C. Little and James Brown, 1864), 380.

“The Union Transport, 287 tons, Captain Consett Wilson, from Huntington Bay, NY April 16th 1783, New York, NY April 24th 1783 and arrived at St. John, NB May 11th 1783,” Loyalist Ships, Dominion Line.

Thomas Peters to Lord Grenville, “The Humble Petition of Thomas Peters, A Negro,” National Archives, London, UK, in Black Slavery in the Maritimes: A History in Documents, ed. Harvey Amani Whitfield (Peterborough, Ontario, Canada: Broadview Press, 2018) ,79.

T.W Smith, “The Loyalists and Slavery,” in The Slave in Canada, (Halifax, N.S.: Nova Scotia Print. Co., 1899), 30.

See The Loyalist Collection:

Journal and Votes of the House of Assembly of the Province of New Brunswick: 1786 - 1819.

Isabelle Goguen is a student assistant for the Microforms Unit at the Harriet Irving Library. She is a graduate of UNBSJ with a Bachelor of Arts degree in English and History with a minor in Psychology.

Add new comment