- Submitted on

- 0 comments

In a 1975 edition of Acadiensis, scholar Murray Barkley described the “Loyalist experiment” in the provinces of New Brunswick and Nova Scotia as a gradual process of ‘mythmaking,’ an “attempt to establish an exclusive Elysium in the North […] based on a hierarchical social structure […] large land-holdings, and a corporate, self-sufficient community of loyal, well-disposed subjects.”

The colony of New Brunswick, Barkley might argue, was therefore essentially carved with the blade of a knife, structured to favour the topmost elements of society – white, landed elites – at the expense of the mass of toilers propping it up with their blood, bones, and muscle. The benefits of these social relations trickled down from the top of the structure, filling the pockets of the middle and upper middle classes, presuming, of course, that they were white and sufficiently fulfilled the image of the “gentile” New Brunswick citizen.

Just some examples of these beneficiaries include William Burtis, Robert Campbell, and Thomas Mullins, three subjects of The Loyalist Collection’s broader “New Brunswick Loyalist Journeys” project. In temperament and personality, Burtis, Campbell, and Mullins strove for their self-interest above all else. They were the perfect sort of men to thrive in colonial New Brunswick.

Loyalty during the American Revolutionary War was a fickle thing. Whereas when the Loyalists submitted their petitions for land grants in the late 1780s, their contributions to the war were described as steadfast and unwavering, during the war itself, allegiances tended to shift and falter according to material circumstance. Historian Mary Beth Norton, for example, has argued rather convincingly that prescribed roles of gender and class had decisive impacts on the writing of Loyalist claims and petitions after 1783. These documents relied in heavy amount upon untruth, exaggeration, and the written fulfilment of presupposed colonial identities.

For example, when captured by American forces, William Burtis wrote a letter that described “very strong marks of contrition, a high sense of his error, & an earnest wish to live than he might by his conduct evince his sincerity” toward the Revolutionary cause. Complications such as these were easily omitted from land petitions and claims in an effort to portray their authors through only the rosiest of lenses.

Dubious claims and outright lies littered the pages of William Burtis’ land petitions. Writing to the New Brunswick government in 1804, Burtis claimed that he had “never received any reward from government except two hundred acres of land.” Of course, this was a falsehood, as Burtis had received over 400 acres of land spread out across his lots in Parr Town (Saint John), Carleton, Long Reach, and Grand Lake within two years of arriving in New Brunswick. He continued, claiming that “Long Island” and the “Duck Islands” contained around 300 acres of unowned land. They instead contained “above 1200 acres.” Whether Burtis’ claim was one based on willful ignorance or acute deception remains unknown.

Immoral actions abound, Burtis went so far as to sue multiple family members over a number of petty squabbles. These include cases made against John McKeel, potential brother-in-law and husband to his sister Ann (McKeel) Burtis, and Richard Bonsall, the then father of William’s second wife Sarah (Reid) Burtis.

Rather than be punished for his instances of deception, trickery, and immorality, Burtis was thoroughly rewarded, and he accrued hundreds of acres of land and over £1500 in legal settlements within his lifetime.

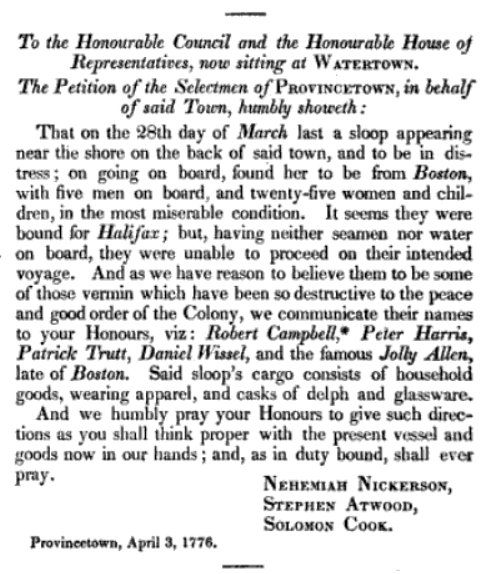

Robert Campbell’s exploits were similar to Burtis’ only in their tendency toward villainy. Campbell, upon fleeing from Boston in 1776, captained a vessel known as the sloop Sally. Aboard the Sally were thirty passengers in total, travelling under Campbell’s guard towards Halifax, Nova Scotia. Campbell, prior to the voyage, had guaranteed to his crew that he was indeed a veteran seafarer of twenty or so years, experienced with his craft and all the duties that it entailed. However, soon after undocking, the Sally collided with two British vessels. The blows inflicted major damage to the Sally’s hull. By the time night had fallen, the friendly British fleet were out of sight, and the sloop Sally and its thirty passengers were left in total darkness. In a fit of rage, one passenger – a man named Jolley Allen – confronted Campbell: “You are the man that has brought me into all these difficulties I am now in; and I do insist upon you doing your duty on board this vessel as long as I am in it, both by night and day.”

The severity of the situation soon became clear. Campbell had lied through his teeth; he had in fact, never sailed outside of a freshwater lake. “[Campbell] had never learned navigation,” wrote Jolley Allen, “he never was on salt water before…. which he had made a fair acknowledgment to me.” After having landed in Cape Cod, officials arrested Campbell and his passengers: “[they] called him a fresh-water captain; that they should not choose to hang a salt-water captain, but a fresh-water captain It would give them the greatest pleasure imaginable.”

Campbell eventually made his way to New Brunswick and settled in Saint John. He brought with him an enslaved person, euphemistically refereed to as a “servant” in official state documents. In an attempt to prove himself a loyal and gentile subject, Campbell made sure to expunge his Loyalist claim of any implicating information. Campbell never received even a word of reproach for his actions by the colonial government.

He was awarded over four-hundred acres of land for his self-inflicted troubles.

Thomas Mullins was a Loyalist firebrand – In 1777, he manufactured a set of false keys that he later used to free a handful of Loyalists from a goal run by the Continental Army. Mullins was also a slave owner and adulterer. To highlight the former events while downplaying the latter seems a major disservice to the historical record, and a simultaneous aid to the colonial legacies that the Loyalists helped enact.

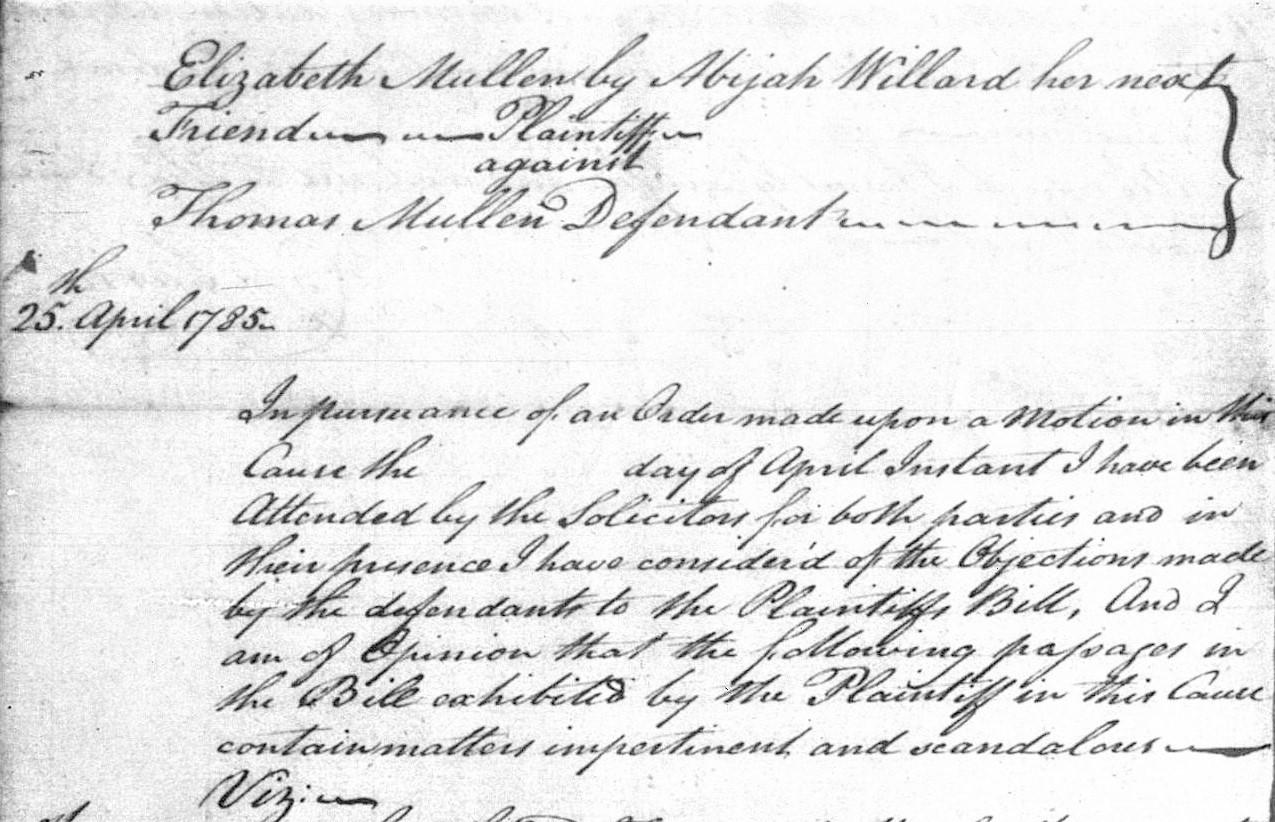

When Thomas Mullins came to New Brunswick in 1783, he left his home, as well as a wife named Elizabeth, in the state of Massachusetts. His personal and familial loyalties soon proved rather dissoluble, with Mullins succumbing to the temptations of an extramarital affair. At some point between his banishment from his home in 1778 and his arrival in New Brunswick in 1783, Thomas met and fell in love with a young woman named Prudence Brown. It seems evident that Thomas and Prudence had quite a connection, since upon coming to Saint John, the two decided to move in together. During their budding relationship, the couple threw caution to the wind, and arranged to be legally married. Thomas now had two wives, two illegitimate children, and one wholly complicated romantic life.

Thomas (for reasons unknown) later invited Elizabeth to visit he and his family in Saint John. When Elizabeth finally made sense of the situation, she fled, furious, to New Brunswick’s Chancery Courts. Her petition was initially thrown out by the court and deemed “impertinent and scandalous.” It was only after her sustained stringent legal attack that Mullins was forced to pay damages.

Like Campbell, Mullins was the owner of two enslaved Black persons. He never acknowledged their humanity, and rather than set them free, sold them to a new owner in 1783.

Mullins was granted over two hundred acres of land upon arriving in New Brunswick, including a lot in Long Reach and another in the city of Saint John.

Settler colonialism dyed every facet of life in 18th and 19th century New Brunswick with its touch, propping up the lives of upperclassmen while subjugating and denigrating the status of women, racialized persons, and the province’s budding working classes. By building an “Elysium” on the backs of the colony’s labouring class, women, Black individuals, and Indigenous Nations, the territory’s Loyalist presence came to be a dominating and domineering one. The lives of William Burtis, Robert Campbell, and Thomas Mullins stand as stark examples of the lopsided relations inherent to settler colonialism – a haunting past that still directly affects our very real, and very actionable, present.

Harrison Dressler is in his fourth year in the fields of History, Political Science, and Anthropology at the University of New Brunswick. He was a researcher and writer for the “New Brunswick Loyalist Journeys Project” and is currently working at the UNB Art Centre and The Brunswickan.

Sources Used

Barkley, Murray. “The Loyalist Tradition in New Brunswick: The Growth and Evolution of an Historical Myth.” Acadiensis, vol. 4, no. 2, 1975.

Bell, D.G. Early Loyalist Saint John: The Origin of New Brunswick Politics, 1783-1786. Fredericton, N.B.: New Ireland Press, 1983.

Norton, Mary Beth. “Eighteenth-Century American Women in Peace and War: The Case of the Loyalists.” The William and Mary Quarterly, vol. 33, no. 3, 1976.

Slumkoski, Cory. "Winslow Papers: 'Indian Schools' in New Brunswick." Accessed November 13, 2021.

Spray, William. The Blacks in New Brunswick. Fredericton, New Brunswick: Brunswick Press, 2021.

Spray, William A. “The Settlement of the Black Refugees in New Brunswick 1815 - 1836.” Acadiensis, vol. 6, no. 2, 1977.

Snook, Edith. “The Recipes of Jonathan Odell and 18th-Century Settler Colonialism in the Maritimes.” Acadiensis, vol. 49, no. 2, 2020.

"W. Burtis, R. Campbell, and T. Mullins," in New Brunswick Loyalist Journeys (UNB Libraries, 2021),

Add new comment