- Submitted on

- 0 comments

Jamaica was the most famous and wealthy sugar island in the British Empire, but with this wealth came big risks that shaped the experience of plantership. The climate, though, that gave also took away - routine threats of devastation were very real from the impact of powerful hurricanes, as reflected today in the images of hurricane Dorian. Disruptions for American loyalists during and after the American Revolution were common, and for one, William Vassall, also an absentee Jamaican sugar planter, life became even more complicated as the 1780s continued to unfold.

The recent hurricane events in the Caribbean coincided with work in a new title in The Loyalist Collection, the British secretary of state’s Original Correspondence with Jamaica, to spark this post. Luckily another title, William Vassall’s Letter Books, was also available to provide vivid personal accounts demonstrating the losses and issues planters faced who found themselves engaged in, what must have seemed, a never-ending struggle against nature.

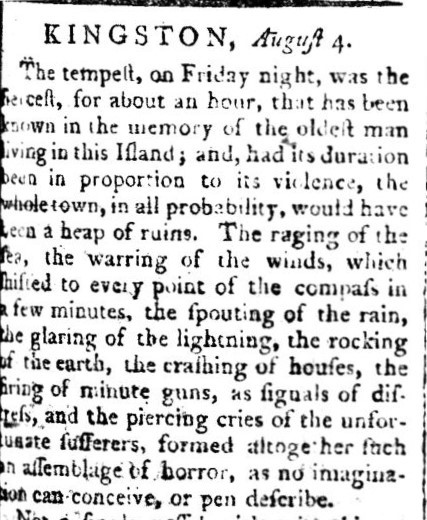

Jamaica had had no significant storms during the 1760s and early 1770s, but then got hit with 5 hurricanes in 7 years from 1780 to 1786. Buildings demolished, ships submerged, shipping and trade thrown into disarray, fields and crops destroyed, and scarcity and death ensued. Eyewitnesses described the physical destruction before them in their letters to the Jamaican government– “blown to shivers”, “laid flat”, “shattered to pieces”, “wash’d away”, “stript”, “a picture of distress.” The Jamaican newspaper, the Cornwall Chronicle, contributed to our sensory understanding in an era without the immediacy of the internet by having published the following report days later, and published elsewhere weeks later:

As a perceived American loyalist or tory, in 1780, William Vassall, now in England, was already dealing emotionally with the results of what he called “cruel and unmerited treatment” in Rhode Island, and the financial fall out from his property having been confiscated in both Rhode Island and Massachusetts, when he finally received word, 5 anxious months after the fact, of “a most melancholy account of the extreme damage done” at his Green Island Estate (also written as Green River) in Hanover Parish by “the most dreadful Hurricane ever known in the memory of man” on the 3rd of October. He wrote exasperatedly, “Not the appearance of a building . . . all being thrown down level with the foundation, & all the Canes & provisions destroyed . . . the last 4 years [I had] met with a continued series of heavy distresses. One following close on the heels of another. I hope . . . God . . . has some good things yet in Store for me and I shall in future largely experience his goodness.” Fortunately for large property owners such as Vassall, potential profits from sugar production would keep him and other planters rebuilding after storms.

In Vassall’s letters, drought also appeared to have been affecting his crop production and bottom line, so after the second hurricane the next year, 1781, he realised he “must use the utmost prudence & Circumspection to guard against ruin.” He recounted some of the havoc created by these disasters:

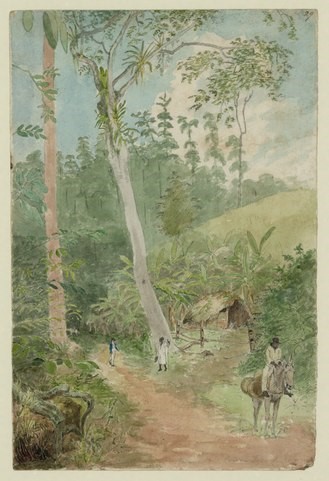

“Negroes were taken off from plantation Works to build new homes for themselves, to plant provisions and to assist in getting Timber for the other buildings & I was obliged to send extra supplies from England. … to Erect new buildings of every kind at an enormous Expence, to buy provisions at Exchange prices, not only to feed my own Negroes but also to feed the Tradesmen employed in the new buildings, to hire Jobbers which was vastly chargeable, to pay high Taxes and my crops for 1781 & 1782 was so greatly reduced, that instead of supplying me with anything for the maintenance of my family, I was obliged to advance upwards of 3000 pounds sterling over and above the whole [?] proceeds of my Crops …to prevent the Estate from going to Wreck & Ruin”.

Emotionally, he admits that he has been so affected “that every Autumn I fear the same unhappy Event”.

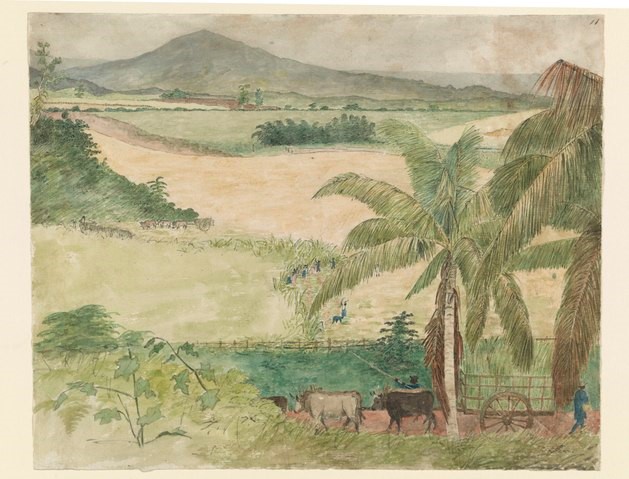

Unfortunately, “horrid devastation” occurred again with the “dreadful hurricane” of July 30, 1784. Jamaican Governor Alured Clarke reported to the secretary of state at England “its baneful influence . . . extended in a great degree over the whole face of the country . . .The Plantain-walks are almost everywhere destroyed, and the ground provisions have suffered so much, that Famine and its certain forerunner, Rebellion of the Slaves, must inevitable ensue, unless the most speedy and ample relief is obtained.” Letters to the Jamaican government by representatives of plantations illustrate their situation post hurricane. William Crombie in his letter presented in council, explained the “Negroes will not have a Morsel to Eat as they always depend on their Plantain Walks.” William Mitchell, Potosi Estate, St. Thomas in the East, provided an even clearer reality – [I] “find myself destitute of every support for my Negroes. I have not a single Plantain Tree standing. Those Plantains that are on the Ground will not be more than a melancholy respite from future want . . . my whole mind is occupied with the Idea of an approaching Famine.”

The hurricane affected Vassall’s canes, plantain and corn. Additional repercussions occurred in England, where complaints about the quality of his sugar imports arose amidst already poor yields from “ordinary” plants. To complicate matters even more, the end of the American Revolution and changes in the political geography of the region had important consequences – orders passed in-council passed by the British government in July 1783 maintained restrictions on trade with America. Vassall wrote, “I am sorry there is a poor market for produce; I hope some way will soon be found out to open a market with America”.

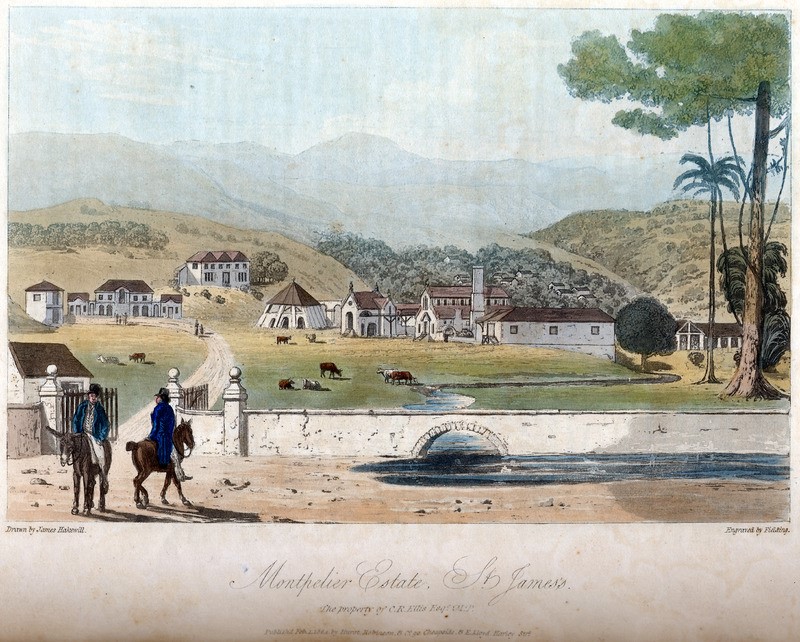

(Courtesy of Wikisource under Public Domain; original by James Hakewill in his work A Picturesque Tour of the Island of Jamaica, London: Hurst and Robinson, 1825)

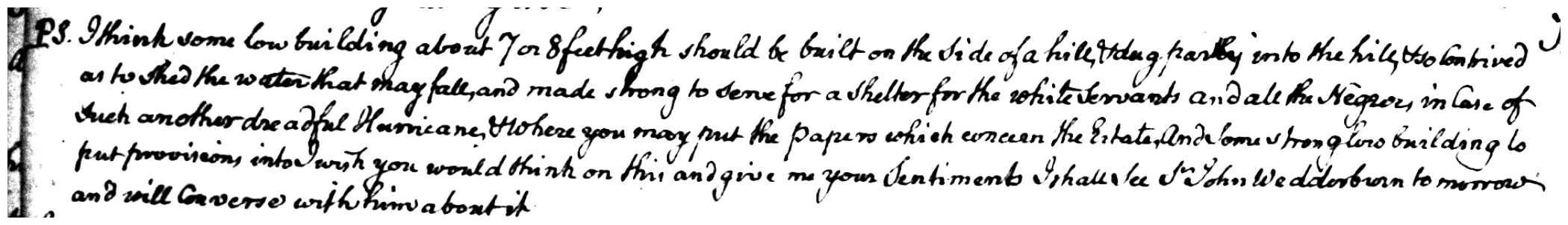

Even with the “repeated misfortunes”, financial difficulties, and precariousness of it all, Vassall was able to adapt and rebound to varying degrees and successes. The 1780 hurricane had him realise the financial “impropriety of expensive buildings” and determined in future to build “low strong snug & the least expensive buildings”, and the 1785 incident had him rethink planting and depending on plantains for provisions as they blow over so easily. Good reasons for continued optimism included increased prices for his products. After the 1785 hurricane, he indicated that sugar sold at “good prices” and expected rum will rise as well (which he also produced). The secretary of state’s and Vassall’s records contribute to our understanding of the mental and physical world of planters during times of natural disasters and accentuate the central role hurricanes played.

Christine Jack is Manager of Microforms, Harriet Irving Library, University of New Brunswick.

Recommended Secondary Sources

Wallace Brown, “The American Loyalists in Jamaica,” The Journal of Caribbean History, 26, no. 2 (Jan. 1, 1992): 121.

Matthew Mulcahy, Hurricanes and Society in the British Greater Caribbean, 1624-1783 (Johns Hopkins University Press, 2008).

Add new comment