- Submitted on

- 0 comments

1776 was a year full of victory and bloodshed for Loyalists and Patriots alike. From prominent American and British officers like George Washington and Richard Howe, to everyday individuals like the Irish-born Charles Cooke, the fate of the American Revolution was a matter of life or death.

Most likely born in 1731, Charles Cooke emigrated to New Jersey in 1766 with strong hopes of creating a prosperous business alongside his brother and life-long business partner, Robert. The two settled near Crosswicks, a small community in Burlington County, New Jersey where they worked as general merchants and plantation owners for the better part of 10 years. The Cooke brothers had no idea of the extent in which the American Revolution was about to affect their lives.

By the summer of 1776, the British Army had managed to secure key victories across the North-Eastern United States, including the capture of New York City. The Patriots had been forced to retreat to Pennsylvania, leaving New York and New Jersey virtually free for British occupation. General George Washington was none too pleased with the events that had transpired in the North, writing to Robert Morris (a key financer of the Revolution) about his doubts and hopes regarding the war: “I agree with you, that it is in vain to ruminate upon, or even reflect upon the Authors or Causes of our present Misfortunes, we should rather exert ourselves, and look forward with Hopes, that some lucky Chance may yet turn up in our Favour.”

However, Washington was insistent on taking matters into his own hands, eventually deciding to craft a plan to retake New Jersey and bolster his army’s morale. Rallying his 2,400 troops, Washington set off across the Delaware River on Christmas morning of 1776. What would follow would come to be known as the Battle of Trenton, one of the most decisive and important victories for the Patriots during the American Revolution.

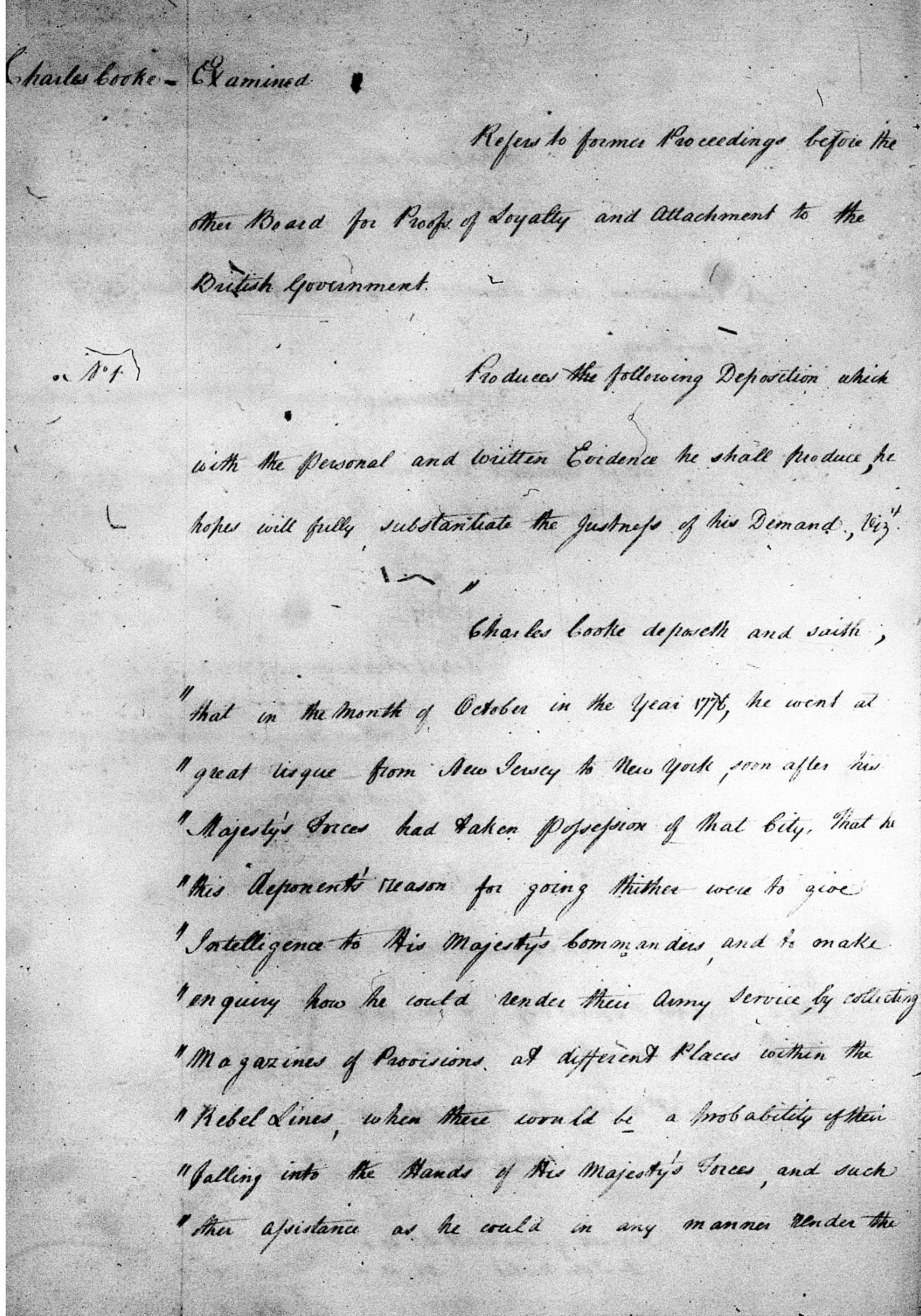

(Great Britain Audit Office. Claims, American Loyalists: Series I (AO 12): 1780–1835. Vol. 74, reel 17, originals The National Archives, England)

Winter looked far different for Charles Cooke, a dedicated Loyalist and hearty Irishman. During the war, Charles was forced to pay large fines for himself and five of his family members when they refused to take up arms against the British. His house had been confiscated and looted and he was forced into hiding in New Jersey, prior to the British Army capturing New York in the summer of 1776. Fed up with how the Americans had been treating him, Charles fled “the vicinity of Philadelphia,” and planned to meet with Admiral Richard Howe in order to convey “intelligence of importance” to the British Royal Army. At the time of his departure, New Jersey had been in total unrest. Patriots and Loyalists alike were being beaten, raped, and robbed, with the roads from Trenton to Princeton being nearly unusable for British and Hessian messengers. General William Howe himself was almost killed by a group of Patriot farmers firing on his patrol on his way back from New York. As Charles Cooke put it in his post-war claim for compensation in 1786, “the New Jersey shores were almost lined with rebels.”

Once in New York, Charles met with Cortlandt Skinner, a brigadier general of the New Jersey Volunteers who fought under allegiance to the British. Skinner commanded Charles to once again return to New Jersey in order to procure provisions for the British Army, who would be arriving in Trenton in December of that year. Secretly working behind “rebel lines,” Charles managed to collect and store “a large quantity of beef and pork” at a set of storehouses that he had erected near Trenton on the Delaware River. Charles successfully evaded the Patriot forces, supplying the incoming Royal Army with sizable rations which they received on December 8th, 1776.

George Washington faced his first trial on December 25th, while crossing the Delaware river. With his army behind him, Washington crossed the barely frozen waters of the Delaware, his army doing its best to traverse the harsh and craggy ice. The army crossed the river with minimal casualties and began their march at around four o’clock in the morning. Soon enough, however, word spread regarding Washington’s advancing troops. In Trenton, Hessian forces sounded the alarms and prepared for the incoming army: George Washington’s surprise attack was foiled.

Despite the Hessians’ small tactical victory, the American blunder wouldn’t matter in the end. Despite a slew of Hessian defenses and counter-attacks led by German commander Johann Rall, the British auxiliaries would inevitably fall victim to Washington’s sheer numbers and superior tactics. After all was said and done, the American army had managed to accrue more than 100 British casualties, with 896 of the Hessian troops being taken prisoner and 400 escaping. Only two of Washington’s men died, and three more were wounded.

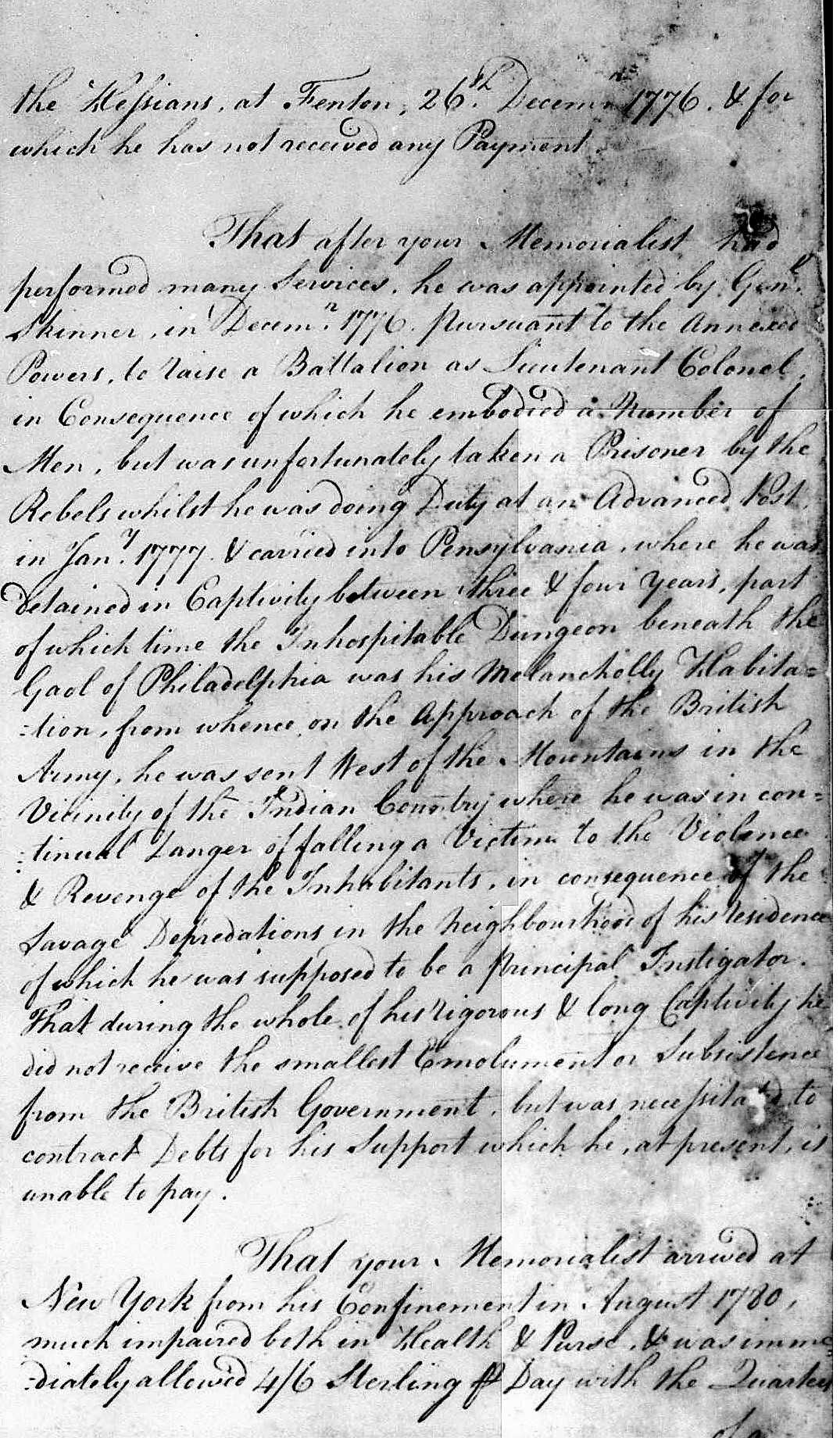

(Great Britain Audit Office. Claims, American Loyalists: Series II (AO 13): 1780–1835. Vol. 108, reel 114, originals The National Archives, England)

However, Charles’ story doesn’t end at the Battle of Trenton. While he never actively participated in the battle, Charles succeeded in his mission to supply the Royal Army with provisions. Charles was then appointed by General Skinner to raise a battalion of men directly after the Hessians lost control of Trenton in December 1776. While rallying men for the British cause, Charles was unfortunately taken prisoner by the Americans and forced to serve over three long years of jail time in Pennsylvania. Be that as it may, being a prisoner of war didn’t keep Charles pinned down. While on parole in Philadelphia, Charles managed to purchase 395 barrels of flour from two men named David Sproat and Samuel Kerr. Using the false name of William Lennox, Charles sent the barrels to a storehouse in Chestnut Hill, a village located around 9 miles west of Philadelphia. The barrels were received by the Royal Army and used as regular rations, which “proved to be a reasonable supply.” Charles would later be sent to Shamokin, Pennsylvania where he would be held until 1778. Upon release, Charles would briefly live in Saint John, New Brunswick before permanently settling in England.

After successfully taking Trenton, George Washington would march North and win yet another battle in Princeton. Soon after, Washington and his army would withdraw to Morristown, New Jersey and stay there for the Winter. By 1783, further Patriot victories would secure United States’ independence and formally end the Revolutionary War.

When it comes to significant historic events like the Battle of Trenton, it’s easy to get bogged down in battle maps, tactics, and stories of daring and courage during battle. People often forget the stories of the simple countrymen working behind the scenes to fight for their beliefs. While the lives of these men and women are almost never as glamorous as the war heroes, their stories are quintessential in accurately telling what truly happened during the American Revolution.

Recommended Secondary Sources

Alfred Hoyt Bill, New Jersey and the Revolutionary War, Vol. 11. The New Jersey Historical Series, (Toronto, Ontario: D. Van Nostrand Company, 1964).

Henry B. Carrington, Battles of the American Revolution: Battle Maps and Charts of the American Revolution, (New York: Arno Press, 1974).

David Hackett, Fischer, Washington's Crossing, Pivotal Moments in American History, (New York City, New York: Oxford University Press, 2004).

Harrison Dressler is an Arts student entering his second year at the University of New Brunswick and is currently working as a summer student in the Microforms Unit.

Add new comment