- Submitted on

- 0 comments

With the scarcity of sources for people of African descent in North America during the eighteenth century, the Book of Negroes is an amazing resource—particularly for those individuals who immigrated to what was to become eastern Canada. The Book was produced at the end of the American Revolution in New York and it nominally recorded Black Loyalists during a time when people of African descent were all too often recorded as mere numbers. Those listed in the Book included both enslaved and free people, but the stability of either state was tenuous in the post-American Revolution Maritime provinces.

The Book of Negroes has risen to prominence recently in popular media and culture with Lawrence Hill’s fictional work, The Book of Negroes, published in 2007. Hill follows the invented character of Aminata Diallo from Africa to slavery in South Carolina, through the American Revolution, to Nova Scotia, and back to Africa via Sierra Leone. A television miniseries based on Hill’s book was broadcast in 2015 starring Aunjanue Ellis.

Why was the Book of Negroes created?

Sometimes called the “Inspection Roll of Negroes”, the Book listed Black Loyalists in New York City in 1783 who intended to go to Nova Scotia, which also included New Brunswick at that time. As well, ships sailed from New York to Quebec, England, Germany, and Jamaica. George Washington had sought the return of slaves who had left their owners during the course of the war to join the British; the British, however, did not comply with Washington’s demand. The British military Commander-in-Chief, Sir Guy Carleton (1724-1808), did agree to make an account of the Black Refugees in preparation for the possibility of patriot slave owners asking for compensation for their losses. Carleton also agreed to hold a Board of Inquiry to handle the claims of slave owners, and some individuals were returned to their previous situations. Therefore, the Black Loyalists’ passage on ships leaving New York was not assured.

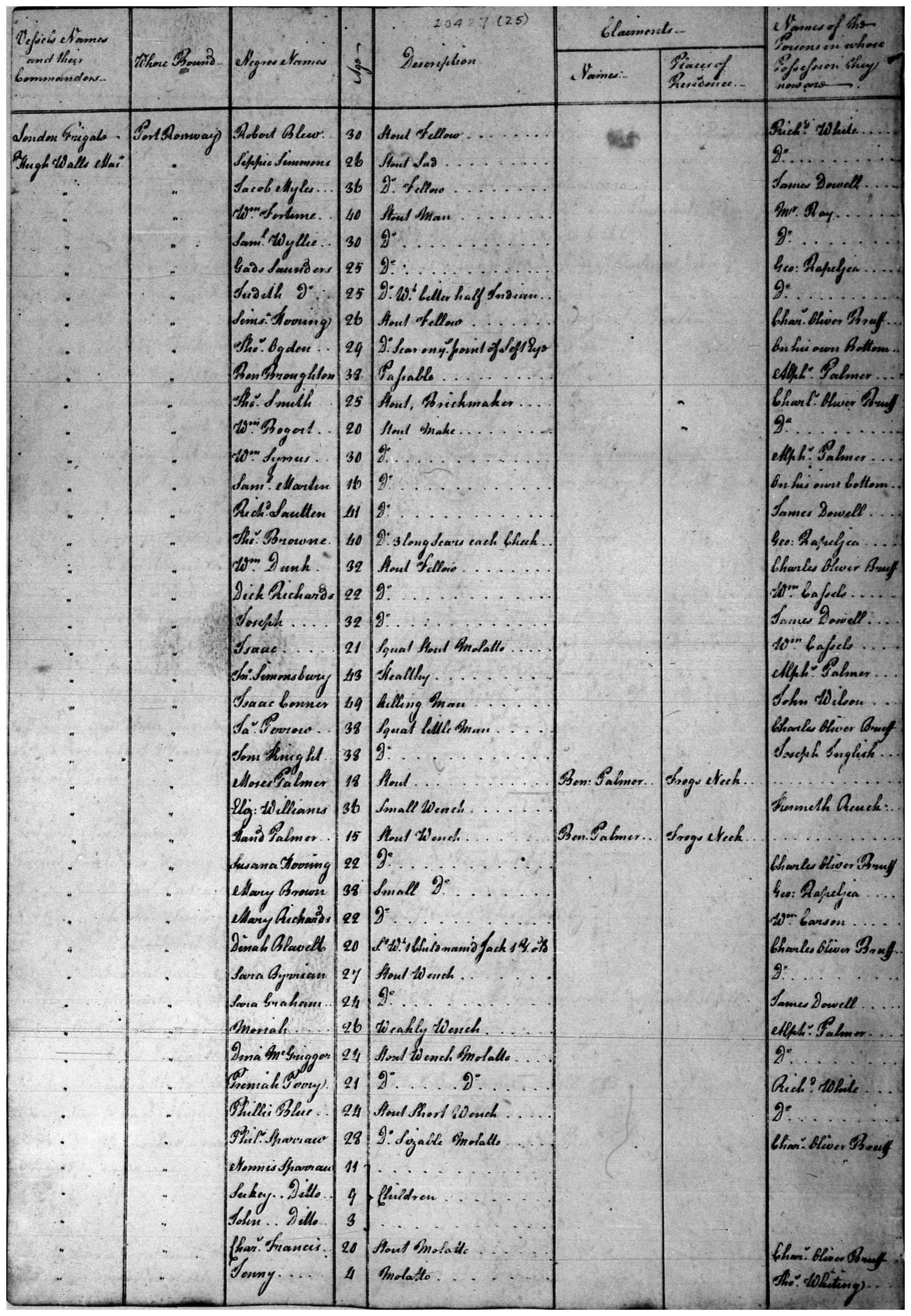

The information compiled in the manuscript includes: ships’ names and their commanders; where said ships were destined to sail; the name, age, and a physical description of approximately three thousand people; possible slave-owning claimants; and other notes such as location of former owners or if the individuals were free born.

A range of descriptions were used for identification and evaluation purposes, most of which came across as reductive, demeaning, and derogatory. The most common adjectives used to portray individuals in the document include “stout,” “ordinary,” “likely,” and “fine,” with more specific descriptive words characterizing physical appearance, ability to work, and ethnic heritage appearing less frequently, such as: “ugly,” “tall,” “small,” “thin,” “squat,” “weakly,” “sickly, “nearly worn out,” “worn out,” “sound,” “passable,” “half Indian,” and “Guinea born.” Specific scars (sometimes indicative of an African birth) and trades were at times noted as well. These descriptive words were combined with a noun: “fellow,” “boy,” “lad,” “girl,” “negress,” “wench,” “Molatto”, “Black,” and “infant” were common. Examples taken from the Book of full descriptions follow: “stout fellow,” “blind of one eye, fine boy,” and “snug little wench.” The finished product appears as a bureaucratic human catalogue.

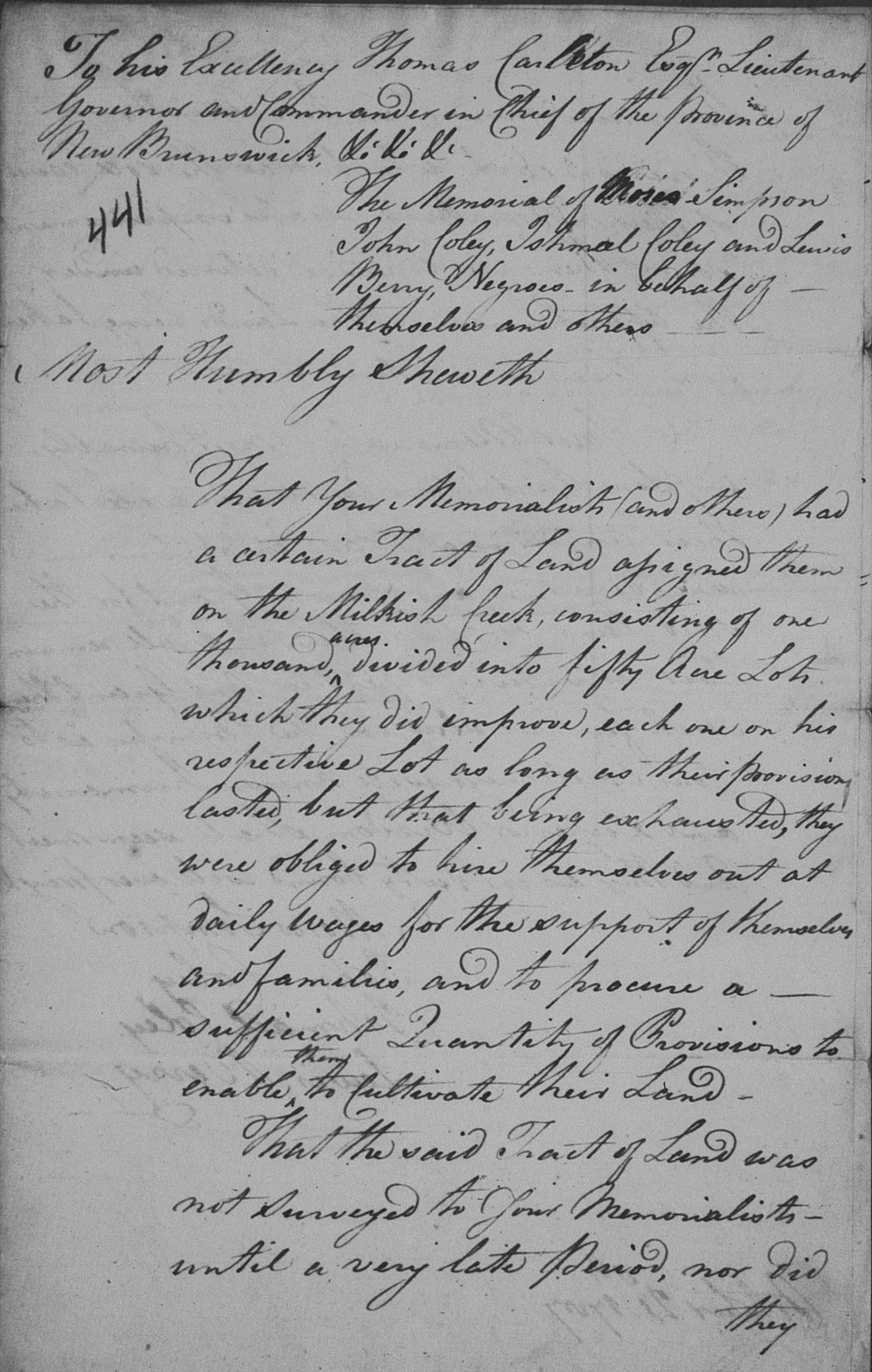

A New Brunswick Settler

John Coley, found in the Book of Negroes as “Jack Coley”, settled in New Brunswick and is listed on a land petition concerning a grant in Milkish Creek, Kings County. Coley came to the St. River with three children on the ship Bridgewater, in the possession of White and recorded as “formerly slave to David Coley Fairfield Connecticut.” Ishmael Coley also appeared on the petition, and he likely knew or may have been related to him, as Ishmael had also been enslaved in Fairfield but to Ebenezer Colley. The petition explained that the memorialists had received limited provisions, and therefore were only able to do limited improvements on the land because they were forced to search out wage labour to support themselves and their families. They asked that the land still be granted to them and that they be allowed time for more planting of crops. This brief insight into Coley’s life shows the extreme tribulations which Black Loyalists had endured and continued to face after resettlement.

When combined with other primary sources, the Book of Negroes allows people who were often invisible in the historical record to be traced, reconstructing their significant and unique life stories.

Sources

There were two original versions of the Book: one created by the British and one by the Americans which display slight variations between the two copies. The British original rendering is held by the British National Archives, while the American accounting is held in the American National Archives. Carleton’s copy of the Book of Negroes is freely available online in a searchable version (manuscript and transcription) on the Nova Scotia Archives website and on the site Black Loyalist. A print version of the American copy of The Book, edited by Graham Russell Hodges, is part of The Loyalist Collection: The Black loyalist directory : African Americans in exile after the American Revolution. The Loyalist Collection holds two microform copies of the British iteration in the Papers Relating to the Negro Refugees: 1783-1839 from the Nova Scotia Public Records and a copy in the British Headquarters Papers: 1747-1783.

Harvey Amani Whitfield, North to Bondage: Loyalist Slavery in the Maritimes, Toronto : UBC Press, 2016.

Leah Grandy holds a PhD in History and works as a Microforms Assistant at the Harriet Irving Library.

Thanks to Annabelle Babineau for documentary research on Black Loyalists in New Brunswick.

Add new comment