- Submitted on

- 0 comments

Acts of espionage and covert operations were widespread during the American Revolutionary War, being utilized by both the British and their North American foes. However, it is the latter group that greatly depended on such stealthy tactics as they were outnumbered in infantry, equipment, and funds. It was at this point in time that the adventures of Silas Deane began, a man who helped achieve victory for the struggling Patriots.

Born in Connecticut in 1738, Deane attended Yale University and went on to practice law for a short time before becoming a successful business merchant. In 1768 he began his political career by serving in the Connecticut House of Representatives and from 1774-1776 was a delegate to the Continental Congress. After his stint as a delegate, Deane was chosen to travel to France for a secret endeavor aimed at securing aid for the struggling American Colonies in their fight against the British; Deane’s efforts would play a pivotal role in determining the outcome of the Revolutionary War.

(William Johnston [Public domain], via Wikimedia Commons)

After its loss in the Seven Years War, France remained bitter towards the British and wished to see their longtime rival’s influence diminish. Thus, the French were quite sympathetic to the American’s plight; however, because the United States was not yet recognized as a sovereign state and also because France did not want to incite tensions with England, there was a great deal of reluctance to directly and openly supply the Patriots with equipment. Therefore, a plan was devised, in part by Deane, to covertly allow the French government to ship necessities to America. This plan was outlined in a letter from Caron de Beaumarchais (a French diplomat who greatly supported American independence) to King Louis XVI:

Let us consider the details of the scheme. The unvarying impression of this affair…should be the delusion, that your Majesty has nothing to do with it, but that a Company is about to entrust a certain sum to the prudence of a trusted agent, to furnish continuous aid to the Americans by the promptest and surest methods, in exchange for returns in the shape of tobacco. Secrecy is the essence of all the rest. (Silas Deane and Charles Isham. The Deane Papers. New York, NY: New-York Historical Soc., 1891.)

After Jean-Marc Nattier [Public domain], via Wikimedia Commons

In essence, a private corporation was to be established, called Roderigue Hortalez and Company, which the French Government would use to channel both funds and equipment (mainly gunpowder) to the Americans. Silas Deane, acting as America’s secret envoy to France, was constantly in contact with Beaumarchais and the fake company in order to ensure that the proper necessities were ordered and delivered. As a result of Deane’s efforts, the Americans were able to prevail during the campaigns of 1777; ultimately, more than two thousand tons of supplies were shipped overseas, including “five hundred and fourteen thousand musket balls, nearly twenty thousand pounds of lead, more than three thousand bombs, and more than eleven thousand grenades” (Peter Andreas, Smuggler Nation: How Illicit Trade Made America, Oxford University Press, 2013).

In addition to procuring war supplies, Silas Deane also oversaw the handling of top secret despatches (official military reports) written by American Commissioners in France such as Benjamin Franklin and Deane himself, which were to be shipped overseas to the American Congress. In 1777, Deane procured the services of Captain Joseph Hynson, who would ensure that the secret documents were safely transported to the United States. However, unbeknownst to Deane, sometime after being hired to work for the American Commissioners in France, Hynson had come into contact with a British agent who persuaded him to work as a double agent for England; apparently, Hynson was mainly concerned with making a lot of money, regardless of who “signed the cheques”. Thus, a plan was organized in which Hynson was to deliver the despatches to the British once they were ready to be shipped out; but, in a last minute change of plans, Deane chose a Captain Folger to transport the documents to America while instructing Hynson to command a brig in western France. Acting quickly while Folger was distracted, Hynson removed the despatches from their packet and replaced them with blank papers. The next day, Folger set sail for America while Hynson fled to England.

Upon being informed that Hynson went to England, Deane assumed he had defected; Deane’s thoughts were reflected in a letter he wrote to Jonathan Williams, an American military engineer: “The wrong-headed, conceited Fool [Hynson] has at last turned out one of the most ungrateful of Traitors…has fled into England, there to help himself by telling all & much more than he had knowledge of”. However, Deane had not yet realized that Hynson had stolen the secret documents: “It is fortunate for us that he knows nothing…it is hoped that his new Patrons will believe everything he invents to serve himself.” (Silas Deane and Charles Isham, The Deane Papers, New York, NY: New-York Historical Soc., 1891.)

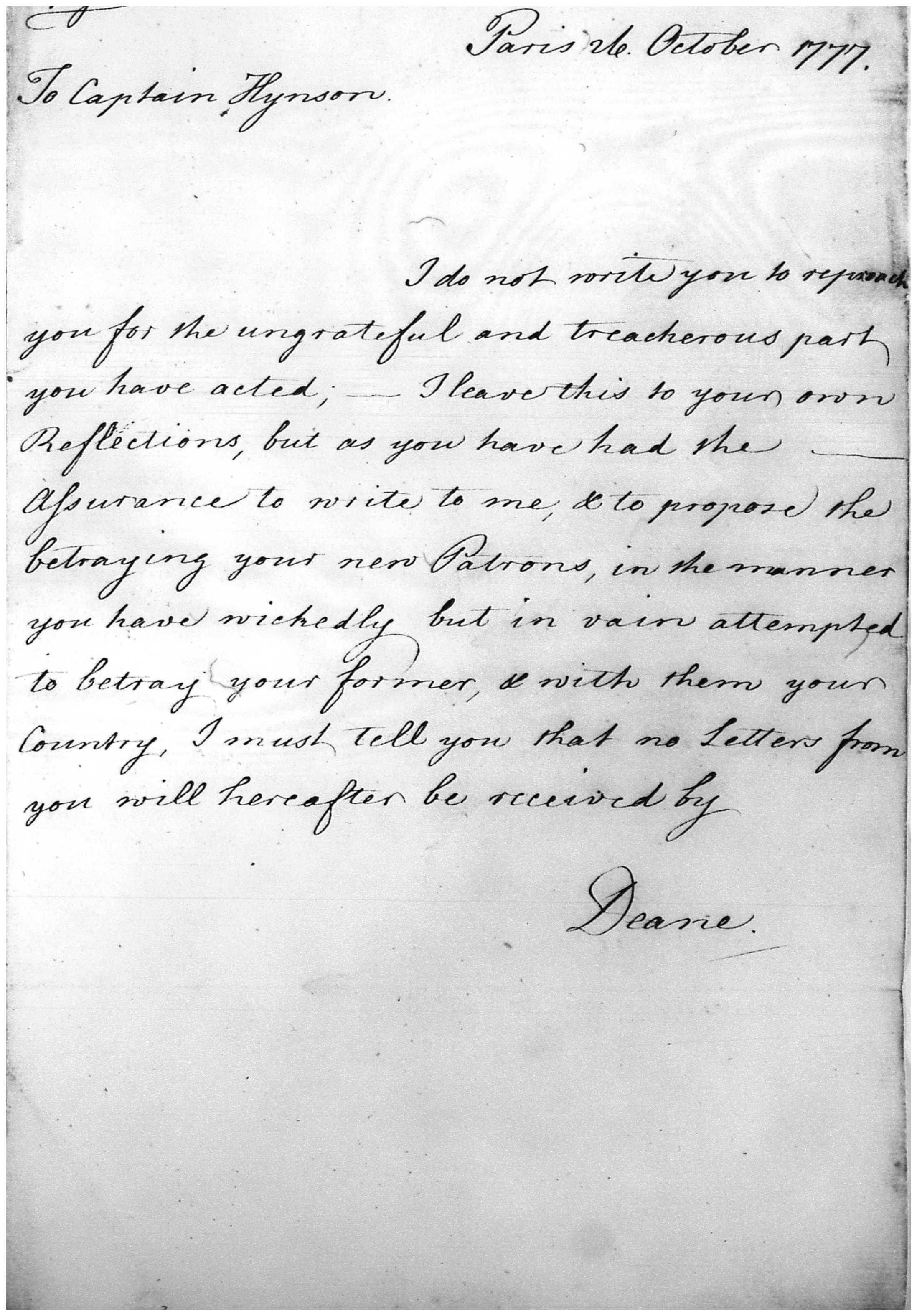

Finally, in yet another act of betrayal, Hynson wrote to Deane offering to supply him with information regarding the British. Fed up with his selfish and backstabbing ways, Deane replied to Hynson with a brief, harsh letter that put an end to their correspondence.

“I do not write you to reproach you for the ungrateful and treacherous past you have acted; --I leave this to your own Reflections, but as you have had the—Assurance to write to me, & to propose the betraying your new Patrons, in the manner you have wickedly but in vain attempted to betray our form, & with them your Country, I must tell you that no Letters from you will hereafter be received by

Deane”

(William Eden, 1st Baron Auckland, Material relating to the American Revolution from the Auckland Papers : 1757 - 1781)

Following the Revolutionary War, both Deane’s reputation and wealth declined; he was accused of financial impropriety while the value of investments he had made plummeted. Ultimately, Deane lived in Europe for much of the remainder of his life. He succumbed to an unknown illness and died in September 1789 in Great Britain.

Greg Watts is a student assistant for the Microforms Unit at the Harriet Irving Library. He is currently in his fourth year of Economics at St. Thomas University.

SUBJECT WORDS: espionage, Silas Deane, American Revolution, patriots, France, Joseph Hynson

Add new comment