- Submitted on

- 6 comments

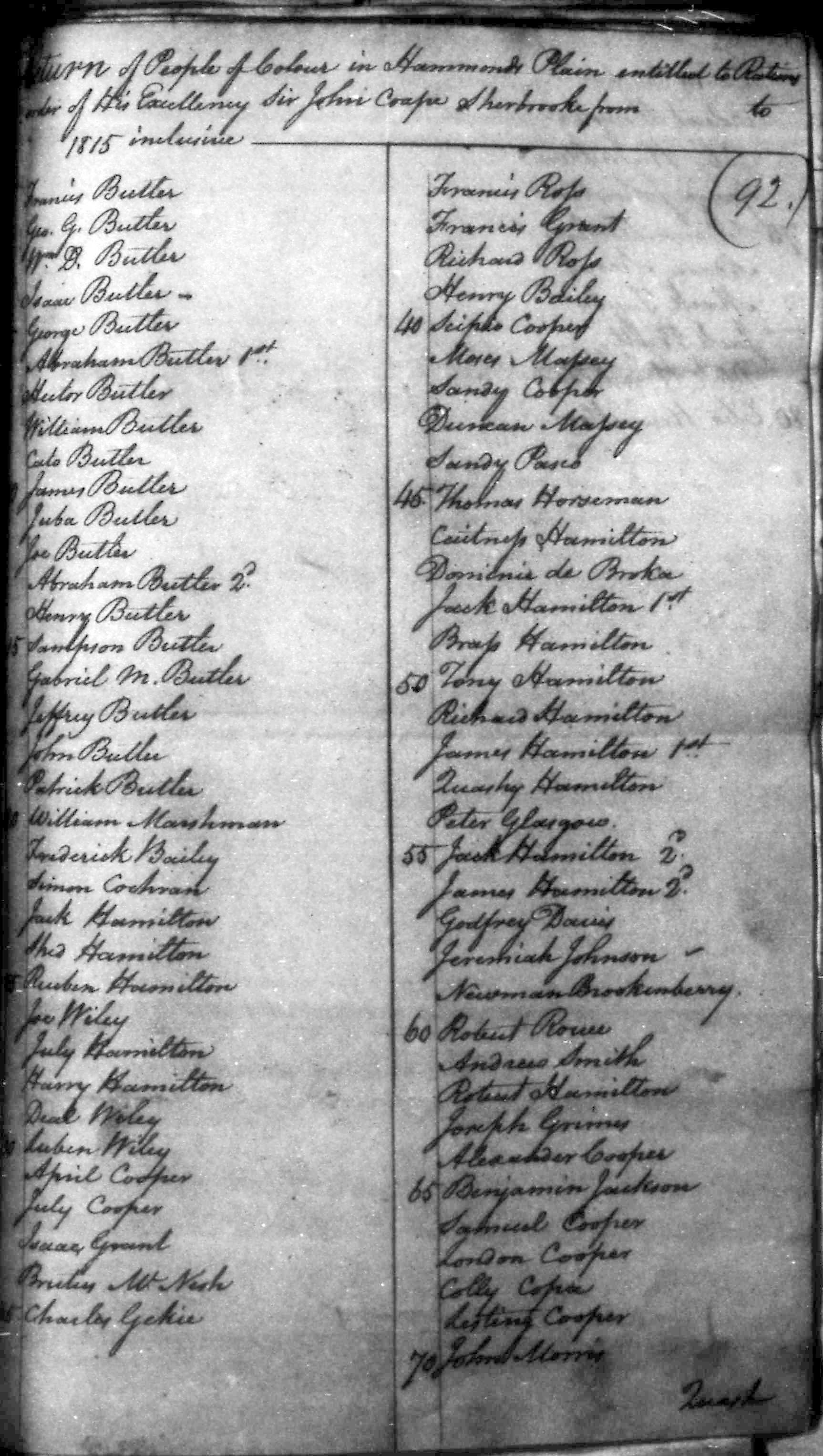

During the War of 1812, an estimated 2,000 slaves escaped America and arrived at Nova Scotia. This number was undoubtedly influenced by Vice-Admiral Cochrane’s proclamation of 2 April 1814, wherein it is stated that “all those who may be disposed to emigrate from the United States will, with their families, be received as……Free Settlers to the British possessions in North America or the West Indies, where they will meet with all due encouragement.” Initially, the Lieutenant-Governor was very encouraging about the Black Refugees’ futures and indicated that he would do “everything to alleviate their distress and render their situation comfortable.” Today it is understood that that there is a relationship between overcrowded and poor living conditions and the spread of disease. Moreover, we are aware that poverty and poor health are inextricably linked, and marginalised groups are often the worst affected. Found at Hammonds Plains, Nova Scotia was one such marginalised group in the early nineteenth century; they were relegated to the fringes of society with a lack of access to rights, resources and opportunities - causing vulnerability. In the winter of 1827, Dr. John Carter, John Starr and Rev. Robert Willis visited this black community of refugees to investigate a “fever similar to scarlet fever” which was heard to be of epidemic proportions. Within the reports that followed, are the details which show the links between health, poverty, and poor living conditions.

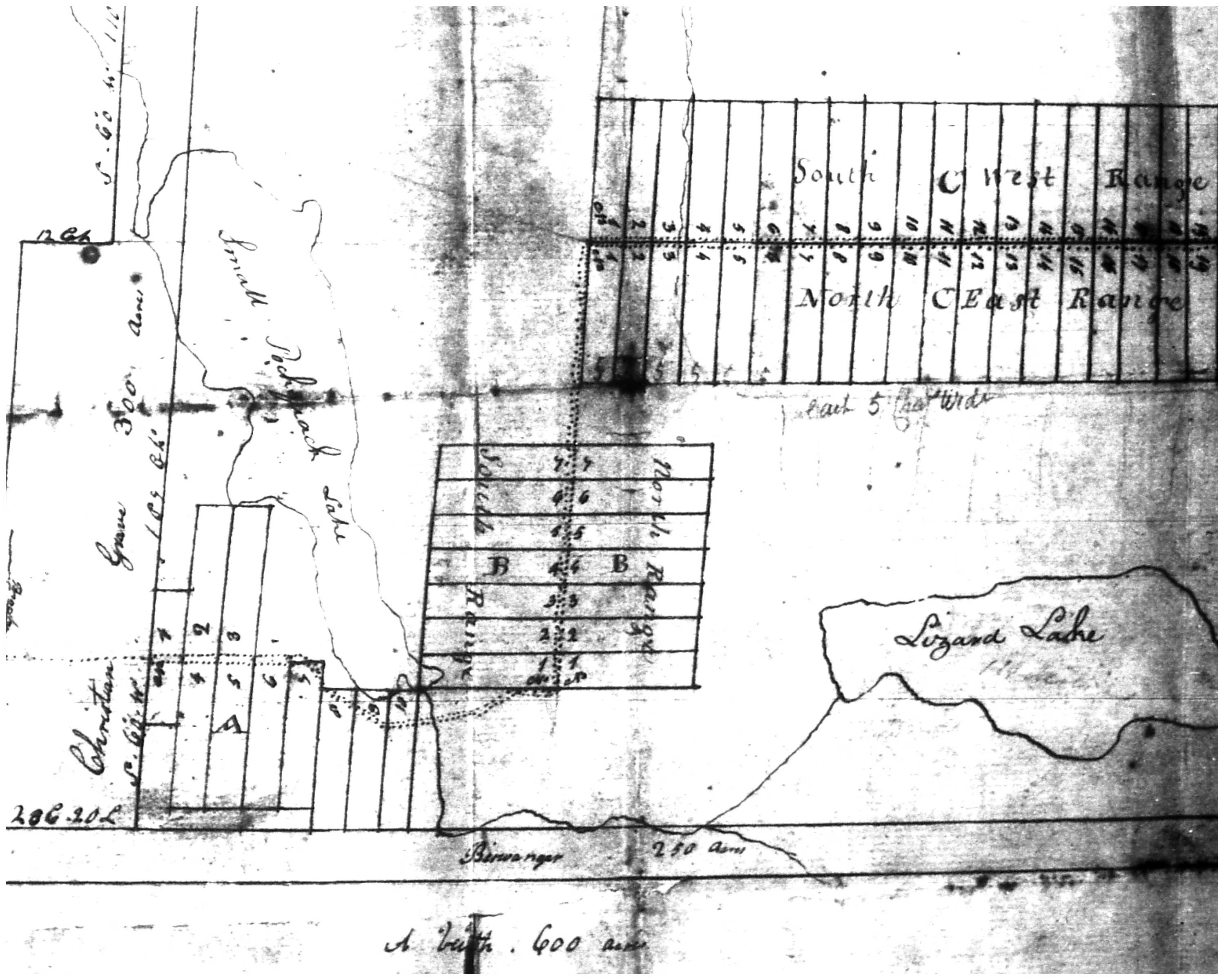

Hammonds Plains (approximately 30 kms from Halifax) had a population of approximately 500 by the end of 1816, and the settlers received a license of occupation for ten-acre lots, often referred to as “waste lands.” (Already one sees potential problems: long distances from market and land too small in size for sustainable food production or for wood to keep the fires burning. This was in addition to unfortunate circumstances such as bad weather, economic downturns, and racism.) Distress was all too familiar and the government distributed grants for such necessaries as potato seeds, foodstuffs, and medicine to the community for more than thirty years. By the end of the first decade, one Halifax citizen’s observations published in The Acadian Recorder on 12 February 1824 was that the black refugees were “worse off free in Nova Scotia than they had been as slaves in the U.S.A. in circumstances of the most extreme poverty and wretchedness, especially during the long winter season.”

After being asked to investigate the “suffering” and extent of the disease in the community, both Rev. Willis, Rector of St. Paul’s Anglican Church in Halifax, and Dr. Carter, assistant staff surgeon with the Army, visited and provided assistance at Hammonds Plains. Both accounts were relayed to the Lieutenant-Governor, via Bishop Inglis, John Starr, and Dr. Alexander Baxter. The terms found in the text are very telling: “distressed”, “suffering”, “destitute”, “diseased”, “abodes of wretchedness”, “unfortunate people”, “naked”, “rags”, “huts”, and the one that really stood out – “distressed inmates.” Within the accounts, our eyes are opened to the details of the seriousness and often fatal consequences of this raging epidemic, and much more: the catastrophic effect on their economies; the mobility complications due to the non-existence of roads and the wide distances between homes; the lack of firewood, clothing and blankets to keep families warm (“scarcely a covering of rags for their bodies”); the close quarters of many people living under one roof which allowed more easily the spread of infections; and the extreme shortness in supply of food and medicine (“some don’t even have this [potatoes] and must beg from neighbours”). The Bishop surmises the effects of the fever are due to “want of clothing, bedding, nourishment and medicine.” Here we see one dilemma: a family was too poor to even get the transportation needed to get the help for their sick at the poor house in Halifax.

What is also revealed in these accounts are the charitable inclinations and reactions to this obvious suffering. The school master, Mr. Campbell, is highly praised for his kind efforts in the community - giving much of himself and reducing the prices of the goods he sells. The church showed advocacy, concern, and assistance on behalf of the church - the Archdeacon helped the family abovementioned with their transportation; and local citizens assisted such as Mr. Holland who gifted 100 hammocks. The government also showed its support by forming a committee to provide continuous supervision, in this instance providing medical and other supplies – molasses, biscuit, meat, tea and clothing.

The medical officer believed the fevers were associated with the epidemic prevalent in Halifax; but it is also true that certain political decisions and indecisions were a factor as well. Between 1825 and the summer of 1827 there was no health officer at the Halifax port to inspect the fever-ridden ships as had previously been done. Furthermore, in 1825, the British Parliament amended the Passenger Act removing the requirement of vessels carrying passengers to the colonies to have medical assistance on board to facilitate emigration from Ireland. However, even Dr. Carter acknowledged the link between poverty, living conditions and health when he deduced the situation, in this case, was and would be exasperated by these factors. The host of major social, medical and public health problems shaped how the Hammonds Plains community members experienced the epidemic and how the epidemic affected them.

Primary Sources

Letters utilised for this blog entry are included in the Papers Relating to the Negro Refugees: 1783-1839 (predominantly 1815-1839) and found in The Loyalist Collection. These are also available electronically on the Nova Scotia Archives’ website under the title African Nova Scotian Diaspora, Selected Government Records of Black Settlement, 1791-1839.

Christine Jack is the Manager of Microforms at the Harriet Irving Library.

SUBJECTS: health, disease, Nova Scotia, Black History, refugees, War of 1812

Comments Add comment

This article

Thank you very much for your

Thank you very much for your comment and encouragement. We have been concentrating on pulling out documents from The Loyalist Collection concerning people of African descent to help in the recovery of lesser known histories.

Hammonds Plains

Scipio cooper

Scipio cooper

Scipio cooper

Add new comment Comments