- Submitted on

- 0 comments

While conducting other research in The Loyalist Collection at the Harriet Irving Library, a collection titled “Indian Affairs: A Collection of Manuscripts: 1761 – 1864” from New Brunswick caught my eye. The first document on the reel was a Peace and Friendship Treaty signed between the “Jediack tribe of Indians” and the British government at Nova Scotia. I immediately had to know more. What I found was that this treaty was not just a singular, one off treaty but was actually part of a series of treaties signed within a two year span, and also part of a string of treaties signed between 1725 and 1779 in the Maritimes that are collectively known as the Peace and Friendship Treaties. I had not heard of the “Jedaick tribe” that was named in the treaty. What I found was that Jediack is a variation of Shediac. The modern day place of Shediac in New Brunswick derives its name from the Mi’kmaq group indigenous to the land. It is plausible it was misspelled by the English. The name Shediac comes from a Mi’kmaq word Es-ed-ei-ik, meaning running far in/far back. The French most commonly spelled it Gedaique or Chediac but there are up to 16 variations of spellings on early maps.

Just like the Numbered Treaties in the Western territories, that were signed a century later beginning in the 1870s, the Peace and Friendship Treaties are contentious. Were they fair and signed willingly, or were they signed under duress? Were the conditions of the treaty properly communicated and understood by both sides before signing? These are questions many debate when studying the Numbered Treaties and the same applies to the lesser known Peace and Friendship Treaties.

This particular treaty was signed on June 25, 1761 by the Mi’kmaq. It was part of a series of treaties that were signed in 1760 and 1761, though the entirety of the Peace and Friendship Treaties encompass the years from 1725 to 1799. The treaties in 1760/61 were signed at a time of great upheaval and change in the colonies of Nova Scotia, as well as in the colony of Quebec. For a long period of time the French had inhabited Nova Scotia (Acadia) and had established productive trading relations and alliances with the Indigenous peoples in Nova Scotia, especially the various bands of the Mi’kmaq. Years prior in 1713, the Treaty of Utrecht had been signed between Britain and France. Along with other concessions, the French ceded Acadia but kept part of the territory (what is now New Brunswick) and Ile Royale (Cape Breton). The French began building the Fortress of Louisbourg on Cape Breton shortly after this.

When war and conflict broke out, as the British and French continually tried to assert dominance in this region, the Indigenous peoples most often sided with the French. The Seven Years War began in 1756 (also referred to as the French and Indian War in North America), and this pattern of alliance was no different. The North American front of the war was fought between the British and the French, heavily aided by Indigenous allies, hence the name “French and Indian War.” At first, the war looked to be in favour of the French, but in 1758 with the final capture and destruction of Louisbourg on Ile Royale (Cape Breton), the British quickly capitalized on their victory, gaining control of Quebec City in 1759 and then Montreal in 1760. Though the war dragged on for another 3 years, it seemed obvious that the British would emerge victorious. They had ended the French dominance in what is now Canada. The Treaty of Paris was signed in 1763, with France ceding all its territory in North America to the British.

With the British victory looming, the Mi’kmaq in the Maritimes signed onto treaties in 1760 and 1761. There will always be debate over the context in which these treaties were signed, but it is safe to assume that the various Mi’kmaq bands were under great pressure to agree to some form of treaty, with the other option being risk to life and limb as enemies of the British. The British had been strategically rounding up and deporting Acadians since 1755, who had been friends and allies to the Mi’kmaq. The threat of a similar fate was looming.

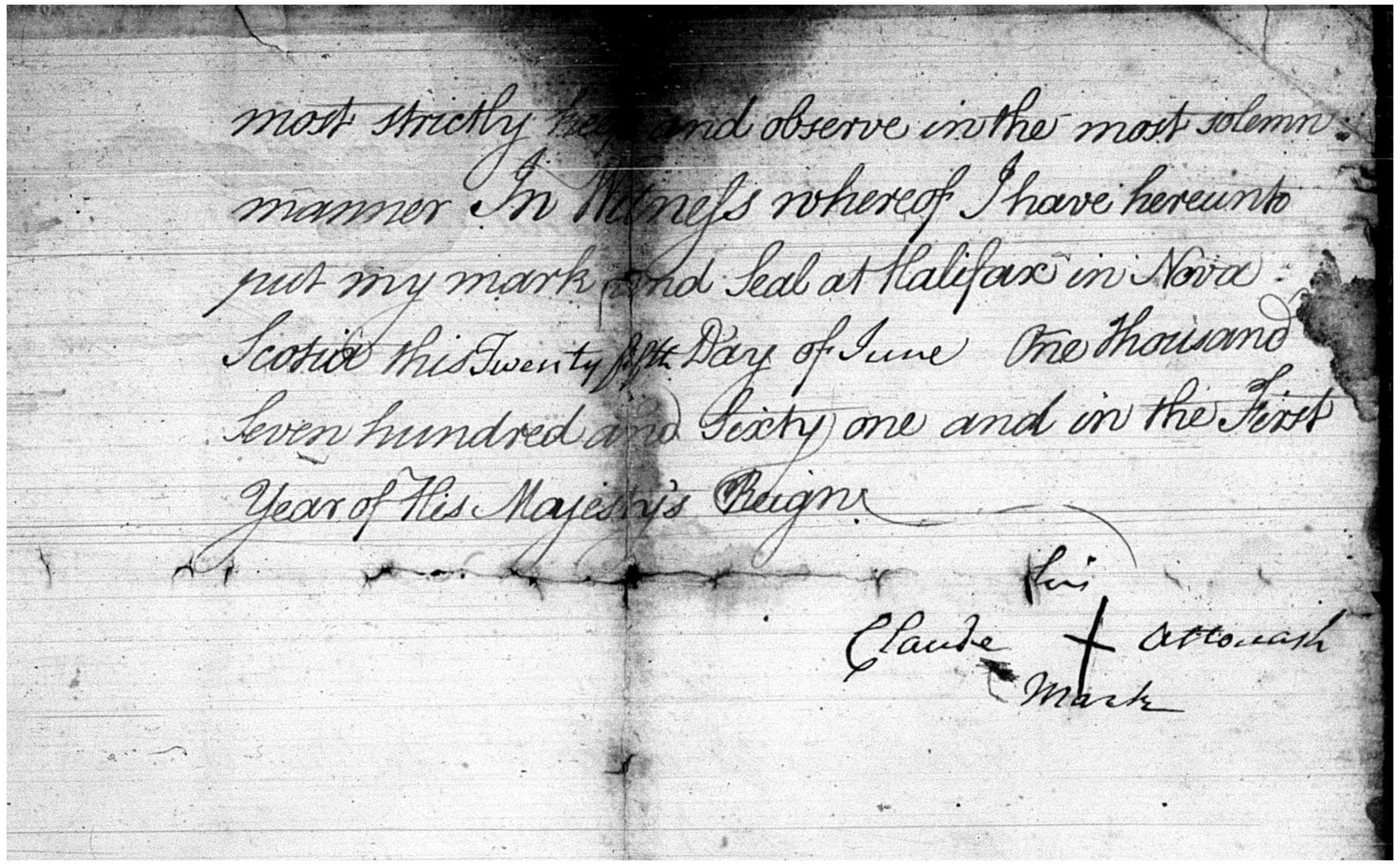

(New Brunswick, Indian Affairs, Indian Affairs : A Collection of Manuscripts : 1761 – 1864, University of New Brunswick Archives)

The contents and terms of this particular treaty, like so many others in Canada, were dictated by the British from a position of power. The treaty reads like a set of conditions that Indigenous people agreed to observe. It is hard not to notice how one sided the treaty reads, with each paragraph or new clause beginning with something like “I do promise for myself and my Tribe” or “I do promise and in behalf of my Tribe.” I could only find one clause in the entire treaty which places some sort of conditions upon the English, it reads:

That if any Quarrel or Misunderstanding shall happen betwixt myself and the English or between them and any of my Tribe, neither I nor they shall take any private Satisfaction or Revenge, but we will apply for Redress according to the Laws established in his said Majesty Dominions.

The Mi’kmaq, after establishing strong, mutually beneficial relations with the French and Acadians are cut off from this source of trade and friendship. Attouash, on behalf of his tribe, promises to not “assist any of the Enemies of His most sacred Majesty King George” and to not “hold any manner of Commerce, Traffick nor intercourse with them.” Not only that but they must only engage in trade at established locations that the British will determine:

And I do further Engage that we will not Traffick, Barter or Exchange any Commodities in any manner, but with such persons or the Managers of such Truckhouses as shall be appointed or established by His Majesty's Governor at Fort Cumberland or elsewhere in Nova Scotia or Acadia.

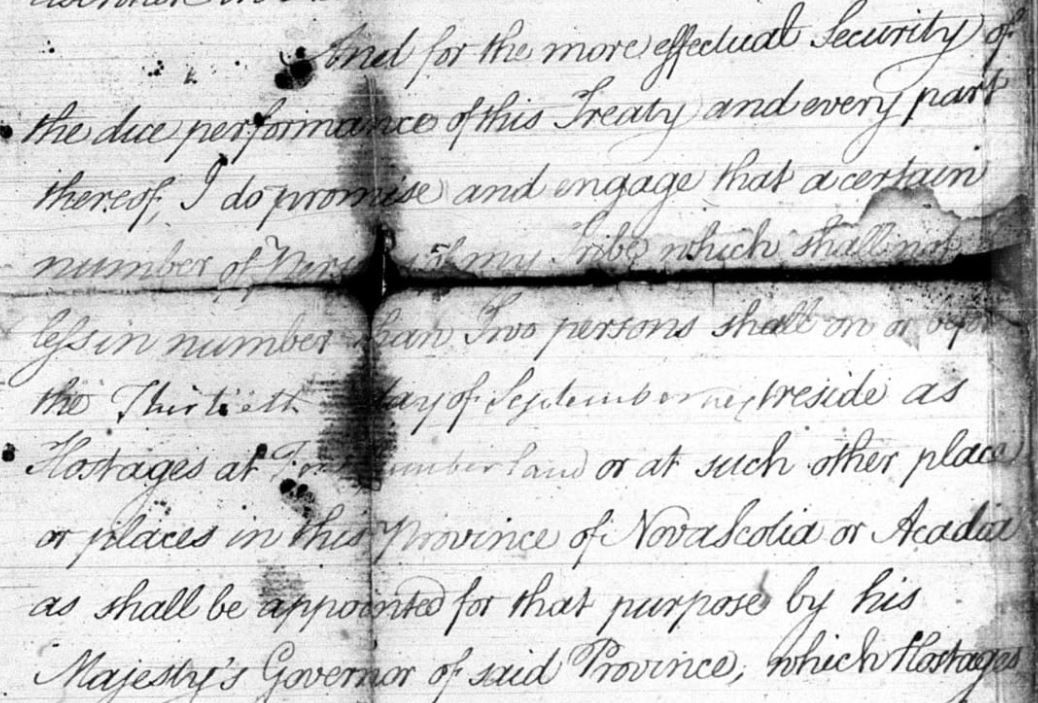

Furthermore, the British would be allowed to hold Mi’kmaq hostages at any of their forts in Nova Scotia to dissuade others from breaking the conditions of the Treaty:

Using the title of “Peace and Friendship Treaty” implies that it is an equal partnership which should place equitable conditions on both sides entering into an agreement. In many cases in Canadian history, we see similar conditions stated within the above mentioned treaty. Clearly, it was not really about “peace and friendship,” it was about establishing control over a region by backing Indigenous peoples into corners and pushing restrictive powers on them all in an effort to control sweeping amounts of territory.

Recommended reading:

William C. Wicken, Mi’kmaq Treaties on Trial: History, Law and Donald Marshall Junior, (Toronto: University of Toronto Press, 2002).

Ken Coates, “Breathing New Life into Treaties: History, Politics, the Law and Aboriginal Grievances in Canada’s Maritime Provinces,” Agricultural History 77, no. 2 (2003).

Sarah Isabelle Wallace, “Peace and Friendship Treaties,” The Canadian Encyclopedia, May 28, 2018.

Note: A digital copy of this document is available through UNB Archives and Special Collections via the Indian Affairs Collection (MG H 54, Item 1, Box 1).

Oriana Visser is a student assistant and researcher in Microforms at the Harriet Irving Library. She is going into her third year as an Honours History student at the University of New Brunswick.

Add new comment