- Submitted on

- 0 comments

(Public domain, courtesy of Wikimedia Commons)

If you were to wander down the Las Vegas Strip today, you would be blinded by the neon lights and the fancy water features of the casinos. In today’s society, you would be hard-pressed to imagine gambling in any other way. However, this practice of weighing risk versus reward has existed for millennia; wall paintings from Pompeii and Red-Attic vases from Greece depict men playing games of dice. Over the centuries, different games were invented in many places, and new gambling cultures began across the world.

In Great Britain specifically, gambling was first officially legislated around the sixteenth century; this made the games of cards, lotteries, dice etc. a purely recreational pastime. By the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries, at the cusp of the Industrial Revolution, gambling or “gaming” returned as a commercial activity, with the rise in horse-betting, lotteries, and establishments built for the sole purpose of gambling. These buildings began as early as the 1600s, but only really took hold in Britain with the rise in urbanization and commercialization of the eighteenth century. Sometimes they operated under the guise of a “gentleman’s club” if the patrons were wealthy, but mostly they were called “Gaming Houses”—what we would call casinos. These establishments became common-place in Great Britain, and consequently in both the United States and in Canada. By the late eighteenth and early nineteenth century the morality of these establishments came into question, and several different Acts banning the practice of gambling were passed. In spite of governmental restrictions, people often decided to take a risk and continue their beloved games for the sake of a reward. The County Court Records from Saint John, New Brunswick demonstrate that while technically against the law, gambling was still a very pervasive part of society.

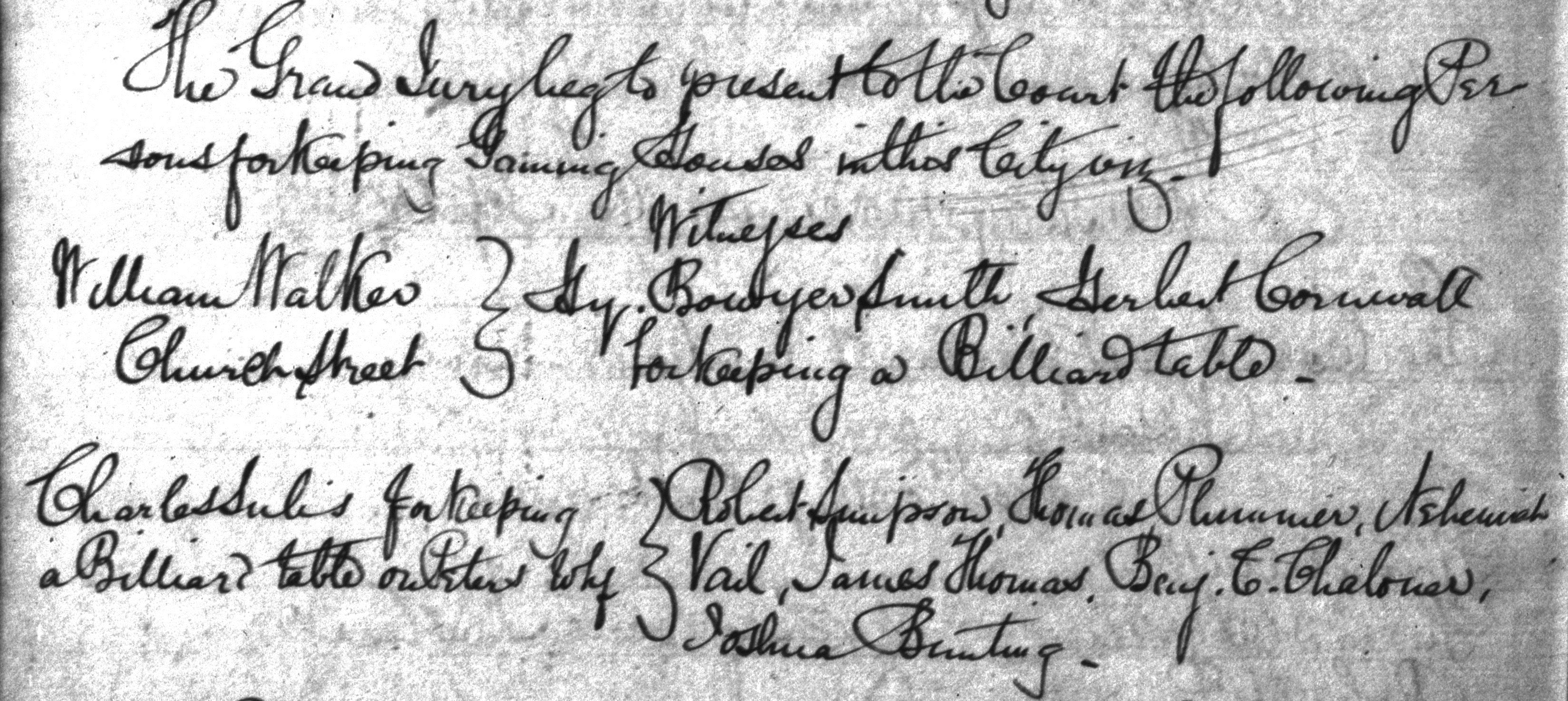

Since gambling on a whole was illegal, it would have been difficult for business-owners to set up establishments meant to promote the custom. This explains why, in Loyalist Saint John, a “gaming house” refers not to a specific type of building, but rather to any place in particular where gambling was being practiced. Taverns were often the easiest place for many people to gather, but taverns meant people, and people meant witnesses; unless all the patrons were trusted, gambling in a public space was especially risky. Sometimes, as was the case of William Walker and Charles Sulis, the practice took place in their homes: in September, 1830, they were both indicted at the Court of General Sessions for keeping a billiard table as a means of gambling.

“The Grand Jury beg to present to the Court the Following Persons for Keeping Gaming Houses within the City:

William Walker Church Street … for keeping a Billiard table

Charles Sulis for keeping a billiard table on Peters Wharf

Billiards was a common activity in Loyalist Saint John; these ones in particular, though, were being used for gambling which made them an illegal trend and punishable by law. Although indictments were made against these two men, they were never formally charged.

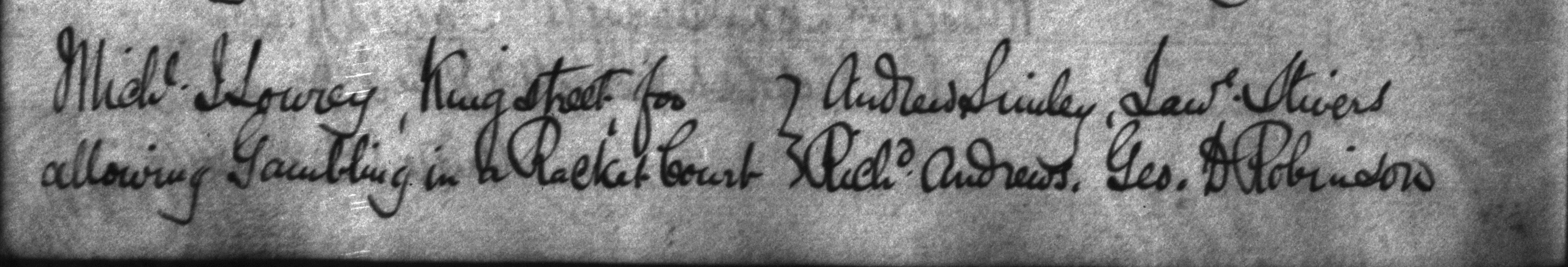

Another frequent culprit of gambling was the sport of tennis, or racket:

“Michael J. Lowrey, King Street, for allowing Gambling in Racket Court…”

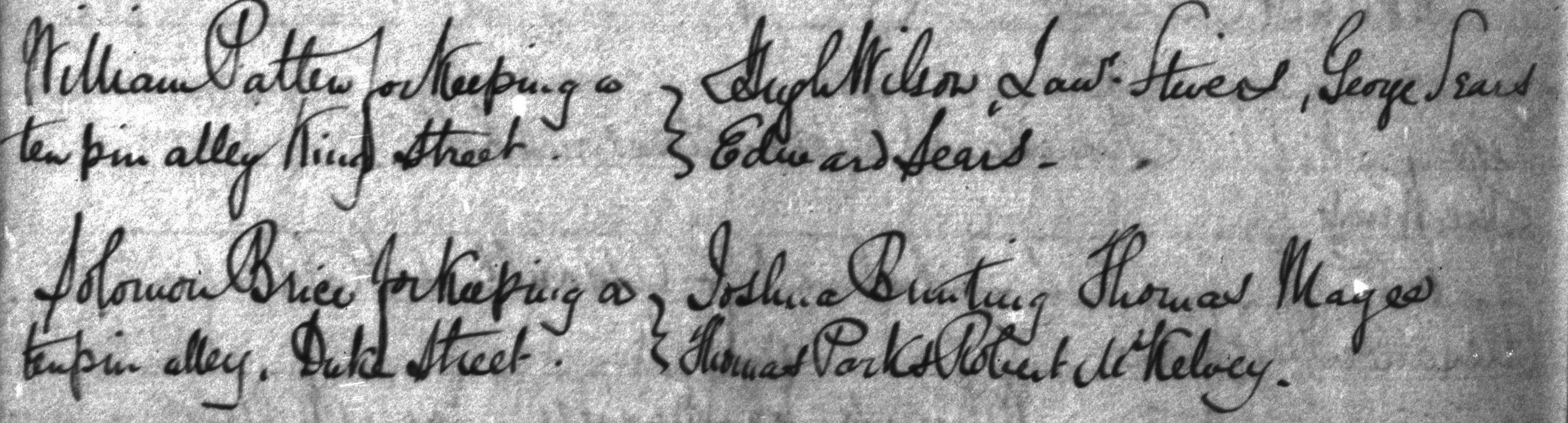

Mr. Lowry here turned an entire racket court into a “gaming house” when he allowed gambling to take place there. Like Charles Sulis and William Walker, he was never formally charged. Both of these indictments were used more as warnings than as cause for a trial. But again, a billiards table and game of racket are fairly ordinary examples of gambling. To avoid the anti-gambling laws, people of Saint John had to get a little creative sometimes, as was the case of Solomon Brice and William Patten in September 1830:

“William Patten for keeping a ten pin alley King Street

Solomon Brice for keeping a tenpin alley Duke Street”

As can be read here, both men were indicted for having kept a ten-pin alley in the City of Saint John. Unless there is another way to use a “ten-pin alley”, these men were indicted for facilitating bets on bowling. It’s ridiculous enough that this crime was brought up in court, but even more outlandish that it was this activity—not the billiards table or the racket courts—that actually progressed to a trial: both Brice and Patten were found guilty and were fined for allowing behavior that was regulated or prohibited on moral or ethical grounds.

Many other examples of Saint John Loyalists partaking in the illegal fun of gambling can be found in the Saint John County Court Records. Check them out!

Secondary Sources

Ashton, John. The History of Gambling in England. London: Duckworth, 1898. E-book.

Leyden, Susan Kathleen. Crime & Controversies: Law and Society in Loyalist Saint John. Saint John: Saint John Law Society, 1987. Print.

Cora Jackson is a student assistant for the Microforms Unit at the Harriet Irving Library. She is currently in her fourth year of her Bachelor of Arts degree at UNB in Joint Honours History-Classics.

Add new comment