- Submitted on

- 0 comments

A portion of “Loyalists in the Classroom: Students reflect on historical sources” is reposted with the kind permission of our friends at Borealia: A Group Blog on Early Canadian History.

Many people have asked me over the years: “why offer a course on the Loyalists of the American Revolution?”

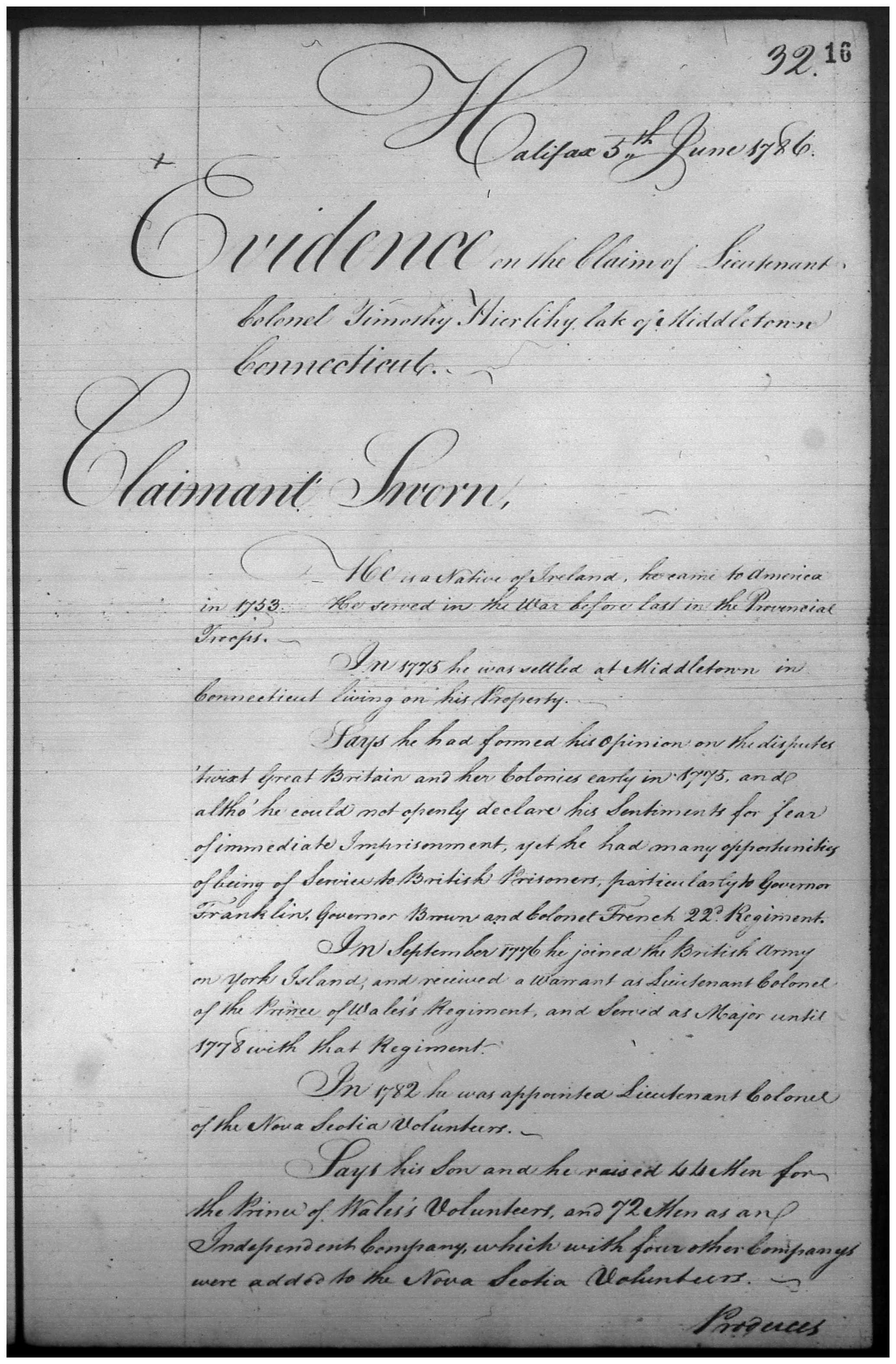

I approach this course as an example of the rewards of “doing” microhistory. By studying this group, students are able to practice their critical skills by assessing primary sources. This opportunity is enriched by the proximity of The Loyalist Collection at UNB Libraries which is one of the richest collections of British and North American colonial records on the continent. Thus, it is imperative to get students into the collection, although it is large and intimidating. The staff in charge of The Loyalist Collection are doing a wonderful job at making the collection more accessible.

By studying the Loyalists, students also come to appreciate what goes into the crafting of historical categories and historical interpretations. For example, in this course we tackle such questions as:

- Who/what was a Loyalist? (not an easy question to answer, as Chris Minty notes in his Borealia posting “The Future of Loyalist Studies”)

- What happens when we apply the categories of gender, race, ethnicity and class to our population?

- Are there merits to approaching this topic from the perspective of loyalism(s)?

- What was involved in “choosing sides” during an event like the American Revolution?

- Were the Loyalists “refugees” like the Syrians of today? Did they experience a “refugee crisis”?

- To what degree was the “American Revolution” a “revolution” or a “civil war”?

Another reward of teaching Loyalist history at UNB is engaging with students from the Atlantic region, many of whom have Loyalist ancestry. Such students craft exquisite research projects by placing their own families within the larger context of the colonial period.

At UNB, it is also possible to call on a range of resident scholars who are interested in the history of the Loyalist era. It has been important for students to see the enthusiasm of researchers in action. Presenters have included Gwendolyn Davies on female Loyalists, David Bell on political unrest in New Brunswick and New York, John Leroux on Loyalist architecture, and Chantal Richard on comparing Loyalist and Acadian identities.

Kings Landing, New Brunswick.

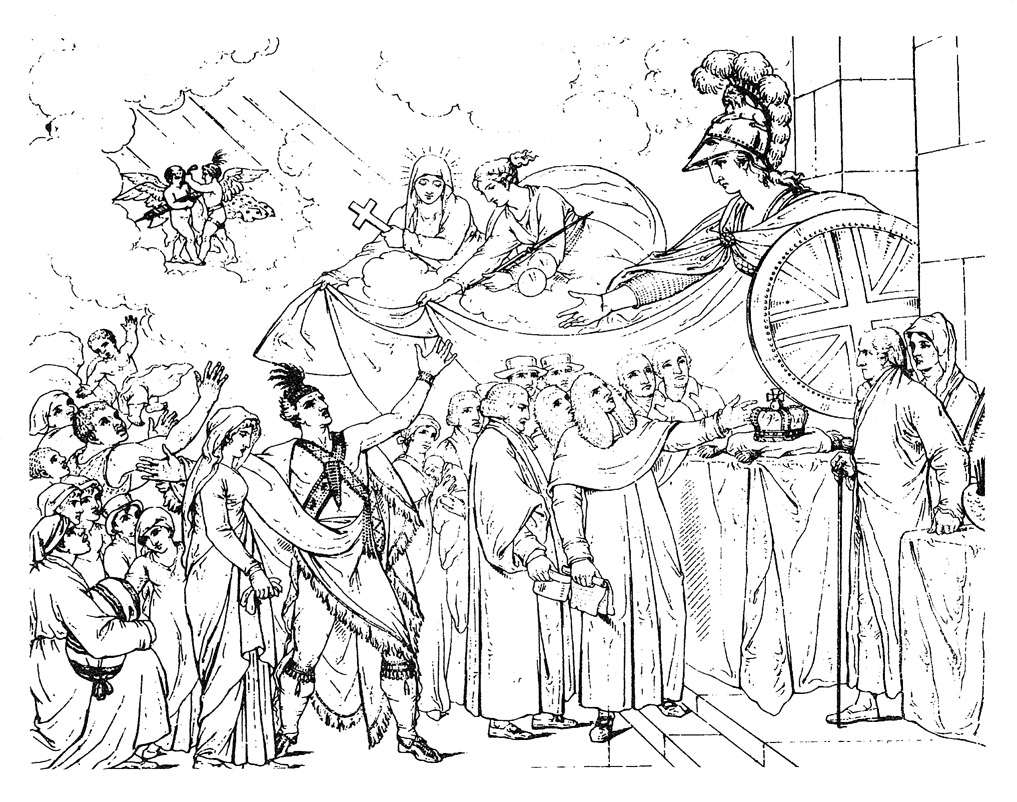

Despite the richness of “the local” in New Brunswick, the most challenging yet rewarding exercise has been to place this course within the multiple contexts of colonial North America, the Atlantic World, the British Empire, and global history more generally. Students respond well to the realization that one can study this population through multiple lenses. I think they have enjoyed comparing and contrasting the experiences of Loyalists in such diverse places as Nova Scotia, Sierra Leone, the Bahamas, Jamaica, and England. I am also very excited by the new literature emerging amongst young American historians on various aspects of Loyalist history, including the reintegration of Loyalists back into the United States.

So, I think I will continue to offer this course as long as I am able, and it will continue to evolve as the literature evolves. Now, back to marking …

Bonnie Huskins teaches Canadian and American history at the University of New Brunswick and St. Thomas University. She studies the local history of Atlantic Canada within the context of a wider web of Atlantic World connections and comparisons. She is also the Loyalist Studies Coordinator at UNB.

Add new comment