- Submitted on

- 0 comments

“What fearful shapes and shadows beset his path amidst the dim and ghastly glare of a snowy light! –With what wistful look did he eye every trembling ray of light streaming across the vast fields from some distent window!” Ichabod Crane was often “thrown into complete dismay by some rushing blast, howling among the trees, in the idea that it was the Galloping Hessian on one of his nightly scourings!”

(Public domain, via Wikimedia Commons)

“The Legend of Sleepy Hollow” by Washington Irving (b. 1783), now known a as classic work of American literature, was first published in 1820 as part of The Sketch-Book of Geoffrey Crayon, Gent. Irving was a son of New York City merchant, but had strong family connections in Westchester County, New York and stayed in Tarrytown as a child, during which time he became enchanted with the area, including the village of Sleepy Hollow. In 1835 he bought a cottage in Tarrytown and was buried at Sleepy Hollow Cemetery upon his death in 1859.

The upstate New York combat zone during the American Revolution made the region around Sleepy Hollow, located between New York City and West Point, a confusing no man’s land or “Neutral Ground” which hosted a traumatic mix of British troops, Germans mercenaries, and patriot militiamen. As described in another of Irving’s short stories, “Wolfert’s Roost”: “In a little while the debatable ground became infested by roving bands, claiming from either side, and all pretending to redress wrongs and punish political offences; but all prone in the exercise of their high functions, to sack hen-roots, drive off cattle, and lay farm-houses under contribution: such was the origin of two great orders of border chivalry, the Skinners and the Cow Boys, famous in revolutionary story; the former fought, or rather marauded under the American, the latter under the British banner.” Residents were caught in the middle of opposing allegiances which resulted in a localized civil war. Irving’s “The Legend of Sleepy Hollow” published forty years after (a generation removed from the trauma of the American Revolution) used elements of historical events described in contemporary documents held within The Loyalist Collection. The short story was to become a famous, early work of American fiction and a part of the fabric of American culture.

The figure of the Hessian plays the role of the ethereal villain in the tale and the imagined enemy of the past: “The dominant spirit, however that haunts this enchanted region, and seems to be commander-in-chief of all the powers of the air, is the apparition of a figure on horseback without a head. It is said by some to be the ghost of a Hessian trooper, whose head had been carried away by a cannon-ball, in some nameless battle during the Revolutionary War, and who is ever and anon seen by the country folk, hurrying along in the gloom of night, as if on wings of the wind.” The symbolism of a ghoulish and wild horseman is a fairly common image in mythology and legends from around the world (Odin, dullahan, Ghost Riders, jhinjhār, Four Horsemen of the Apocalypse, Herne the Hunter, etc.). Literary critics such as Robert Hughes have characterized the story as a transformation of the traumatic history of the American Revolution into satire and an outlet for telling tales of survival and death, essentially making historical events into ghost stories.

(Public domain via Wikimedia Commons)

The historical reality of the Hessian is much different than the poetical and imaginative description in Irving’s work. The term “Hessian” refers to the special German auxiliary troops used by Great Britain during the American Revolution; to be specific, it refers to soldiers from the German principalities of Hesse-Cassel and Hesse-Hanau who had developed a great reputation as warriors, but troops were also sent from Brunswick, Waldeck, Anspach-Beyreuth, and Anhalt Zerbst. The Hessians served under their own officers, and a treaty agreement existed between former allies during the Seven Years War King George of England and German rulers, who received payment rather than going directly to the soldiers. Much of the negative connotation surrounding Hessians for Americans emanated from the idea that foreign mercenaries were being used against British subjects and patriot propaganda, such as stories of cannibalism perpetrated by Hessians. The Hessians, in turn, saw the patriots as ungrateful subjects living in wealth for rebelling against their king as well as voicing sympathy for loyalists and enslaved people of African descent.

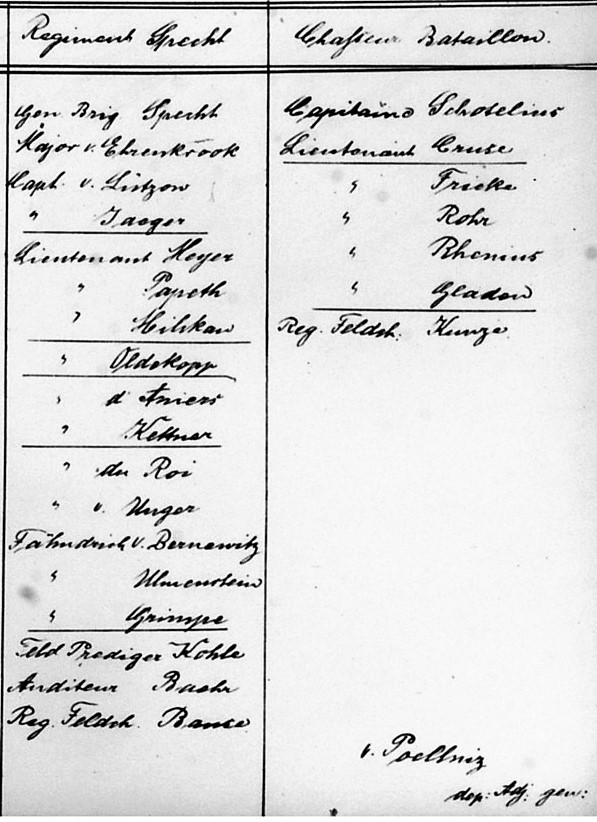

The Loyalist Collection holds a copy of the Hessian Documents of the American Revolution: 1776 - 1783, known as the Lidgerwood Collection, from Morristown National Historic Park in Morristown, New Jersey. The Lidgerwood Hessian Transcripts include accounts of military campaigns (including detailed battle accounts) and offer a record of the life and experiences of the German soldiers in America. They also give insight into the patriot, loyalist, and British forces.

Hessian officers were mainly career soldiers; however, rank and file soldiers were a mix of veterans, young farmers who had only had limited militia training if any, and recruits who were often gathered using aggressive and coercive practices. They were knows for their corps of Jaëger (translated as “hunters”) armed with short, heavy rifles. Sleeves on the German uniform coats were cut short to make the soldiers appear larger. Many units were referred to regularly by English or French translations of their German names. Six women were permitted for each company; therefore, woman and children accompanied the Hessians.

Out of the approximately 30,000 German soldiers who served during the American Revolution, one quarter died, and a few thousand chose to remain in North America at the end of the conflict. The American Congress used various strategies to tempt the Hessians to desert, although it was often relationships forged with local women while on garrison duty or being kept as a prisoner which enticed the German men to leave the army. It is often difficult to trace the lives of former Hessian soldiers, due to name variations and the presence of other German settlers prior and after the war. Although the retained, group memory associated with Hessians in North America is negative, they became integrated into the fabric of many communities across the continent. Indeed, they certainly did not remain to haunt the population as headless horsemen.

Next week: Part 2, The Hanging of Major André

Secondary Sources

Rodney Atwood, The Hessians: Mercenaries from Hessen-Kassel in the American Revolution, New York: Cambridge University Press, 1980.

Robert Hughes, “Sleepy Hollow: Fearful Pleasures and the Nightmare of History,” Arizona Quarterly, vol. 61, no. 3 (Autumn 2005), pp. 1-26.

Jacob Judd, “Westchester County” in Joseph S. Tiedemann and Eugene R. Fingerhut, eds., The Other New York: The American Revolution Beyond New York city, 1763-1787, Albany, New York: State University of New York Press, 2005.

Merz, Johannes Helmut, The Hessians of Nova Scotia, Seventh Town Historical Society, 2005.

___________________, The Hessians of Upper Canada, Ameliasburg, ON: Seventh Town Historical Society, 2008.

Philip R.N. Ratcher, King George’s Army 1775-1783: A Handbook of British, American and German Regiments, Reading, Berkshire: Osprey Publishing Ltd., 1973.

Leah Grandy holds a PhD in History and works as a Microforms Assistant at the Harriet Irving Library.

Add new comment