- Submitted on

- 0 comments

Slave-based sugar cultivation on the island of Jamaica was nothing if not brutal. In the late eighteenth century, it was also rapidly industrializing. By professionalizing management practices, embracing technological change, and increasing rates of reproduction among enslaved populations, planters could momentarily distinguish themselves in a crowded scene of ever-competing estates.

One man, an absentee planter and American loyalist named William Vassall, whose volumes of letter books have survived over two centuries of wear and tear, celebrated just such a process. “It is a planter’s interest,” writes Vassall, “to make a good crop, & at the least expense possible. In order to do this he must consider in what manner he can improve his land so as to make the same quantity of sugar with the least labour, and with the smallest expense.”

One such measure was the gradual transition away from “skimming coppers” to what he calls “coch coppers”, a technology that required marginally more fuel than its predecessor while producing more sugar of a higher quality. Another agrarian innovation on Vassall’s plantation was his discovery of the “Trelawney method” of ratooning sugarcane, which saw the canes groomed, temporarily excavated, and refilled with manure to speed their growth after cultivation. These innovations, he proclaimed, would aid in greatly reducing “the hard labour of the estate… & these will be a very great if not a total saving of hired labour.”

Still, technological innovation could only stunt the disabling effects of sugar cultivation so much. Poor nutrition, dramatic rates of infant mortality, the naturally strenuous conditions of sugar production, and inhumane punishments including whipping were still widespread throughout the island. The era’s plantations were notorious for serving meagre and innutritious rations to their bondspeople. Vassall himself is on record in serving his enslaved population plantains and sugars, as well as oatmeal, pears, and beans “to give to the Negroes for a change of diet, to give to weakly & sick Negroes, & to children, and to guard against illness.” On his plantation, most of the enslaved seem to have lived in “snug stone or brick house[s]” constructed in nearby glades and fields. His managers were told to care for the sick and the infirm, high quality reserves were left for those with a want for them, and some measure of housing was provided for the enslaved. Vassall’s strategies for preserving his estate’s labour force might therefore seem relatively involved and conscientious.

Yet, no matter Vassall’s efforts, his plantation’s slaves died regularly and without prejudice. In January of 1790, his estate was struck with what he calls “the rot”, a form of contagious and debilitating sores. By February of that year, one “fine field Negro woman” had died of the influenza. This continued without repose for multiple years, with Vassall writing in December of 1791 that he hopes “the Negroes have all got well.” In a particular telling passage, Vassall writes to his friend and plantation manager John Graham to ask what he thinks “is the reason that my Negroes on Green river Estate are so much more afflicted with sores than on any other estate.” While exact explanations were never expounded upon in his letters, Vassall was aware that his estate was constantly ravaged by disease, death, and malnutrition – even more so than the other plantations located in the region. William Vassall’s efforts to ameliorate the conditions of the enslaved, no matter how limited in scope these ameliorations were, had failed miserably.

As an absentee planter, Vassall owned and operated the Green River plantation from across the Atlantic Ocean. He lived in Clapham Common, London, England, and therefore had to employ a host of managers, lawyers, and overseers to manage sugar production on the island. This meant that many employees remained little more than faceless names to the likes of William Vassall.

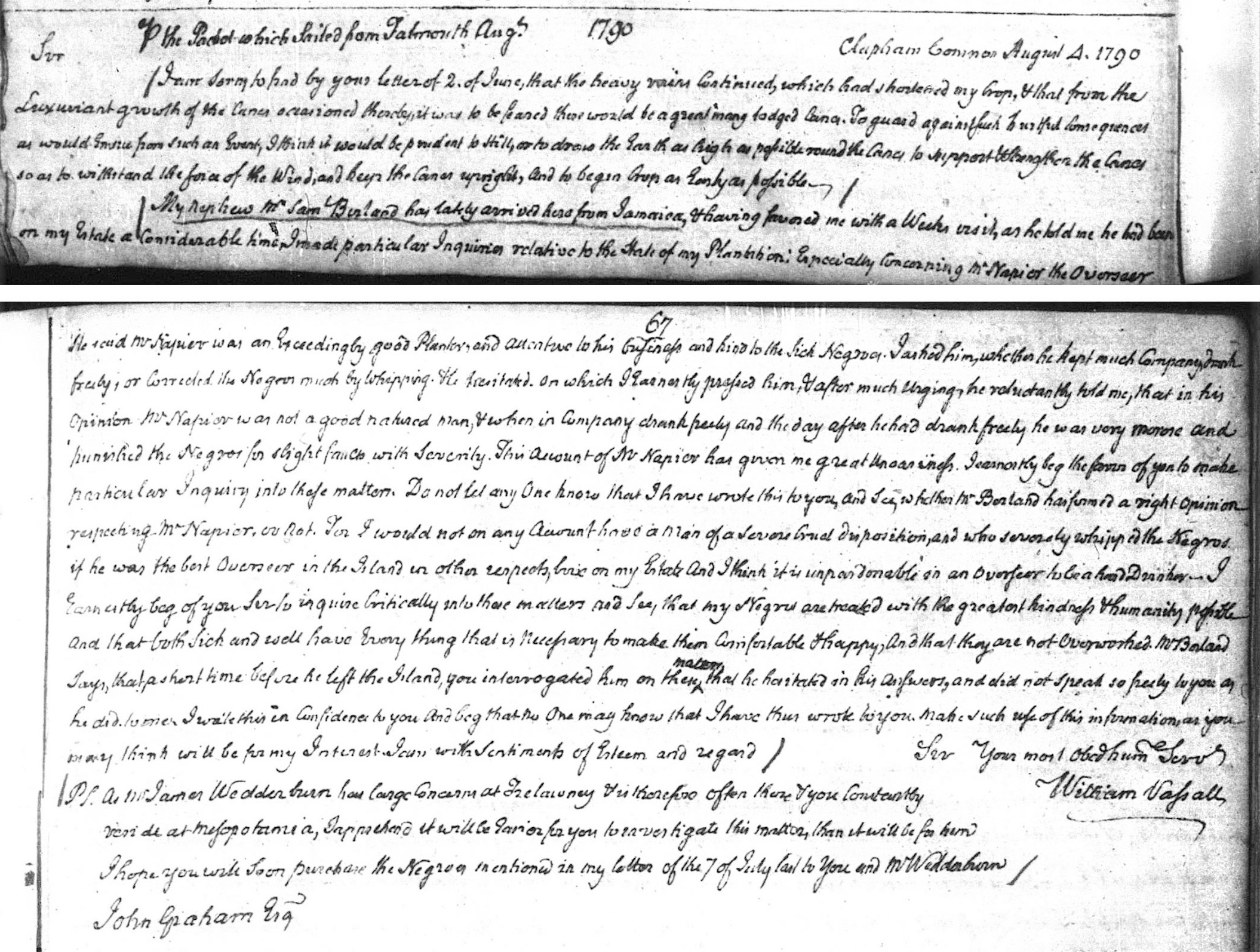

For instance, in the month of August 1790, Vassall took particular interest in the seemingly hazy character descriptions of one “Mr. Napier”, the estate’s long-term overseer. Up until this point, Vassall believed Napier to be “an exceedingly good planter and attentive to his business and kind to the sick Negroes.” It was only once Vassall’s nephew Samuel Borland visited him in Clapham that Napier’s true nature began to come to light. Still, the interrogation was extensive and slow going. Vassall writes that upon being questioned, Borland “hesitated, on which I earnestly pressed him.” Only “after much arguing,” did Borland “reluctantly” tell Vassall “that in his opinion Mr. Napier was not a good natured man, & when in company drank freely and the day after he had drank freely he was very morose and punished the Negroes for slight faults with severity.” Vassall himself seems shocked that such abuses could occur on a sugar plantation, stating that “I would not on any account have a man of a severe cruel disposition, and who severely whipped the Negroes if he was the best overseer in the island in other respects, live on my estate and I think it is unpardonable in an overseer to be a hard punisher.” The very professional hierarchies that Vassall had imposed on his estate counterintuitively limited the amount of direct control he had on his plantation and the enslaved people that lived there. Borland and other lesser officials were clearly afraid to speak up, with Vassall writing “that a short time before he [Borland] left the island, you [John Graham] interrogated him on these matters that he hesitated in his answers, and did not speak so freely to you as he did to me.”

Sugar plantations were by nature coercive institutions, where severe punishment and monetary incentives led individuals to shirk their employer’s professional and moral directives. On the plantation, Vassall’s ability to enforce principled stances and a perverted form of “humane” slavery was limited at best, and a fool’s errand at worst. While amelioration efforts did take place on his estate, their successes were lacklustre and barely curbed the rampant rates of death and disease on the plantation. Finally, the nature of being an absentee planter meant that Vassall’s own moral imperatives were of secondary concern to the officials and overseers actually running the plantation, often leading to unforeseen and undocumented abuses and malpractices.

Sources Used

Keith Mason, "The Absentee Planter and the Key Slave: Privilege, Patriarchalism, and Exploitation in the Early Eighteenth-Century Caribbean," The William and Mary Quarterly 70, no. 1 (2013): 79.

Kenneth Morgan, "Slave Women and Reproduction in Jamaica, C.1776-1834," History 91, no. 302 (2006): 231-53.

William Vassall. 1715-1800. Letter Books : 1769 – 1800, UNB Libraries, The Loyalist Collection.

Harrison Dressler is a third year History and Political Science student at the University of New Brunswick, currently working as Research Intern at AIDS New Brunswick.

Add new comment