- Submitted on

- 0 comments

The quest to pinpoint historical places, even those from the late eighteenth century, can prove a difficult endeavour for researchers and requires the skills of both Sherlock Holmes and an experienced historian. In New Brunswick, for instance, two main cites existed under alternate names for the early period of loyalist settlement: Parrtown or Parr Town for Saint John and St. Anne’s Point for Fredericton. In the process of creating a GIS story map plotting the lives of loyalists in York County, New Brunswick, and transcribing New Brunswick county court records, we at the Micoforms Unit of the Harriet Irving Library have had to do some serious detective work to make a final determination on settlement and community sites, land grant locations, and geographic features.

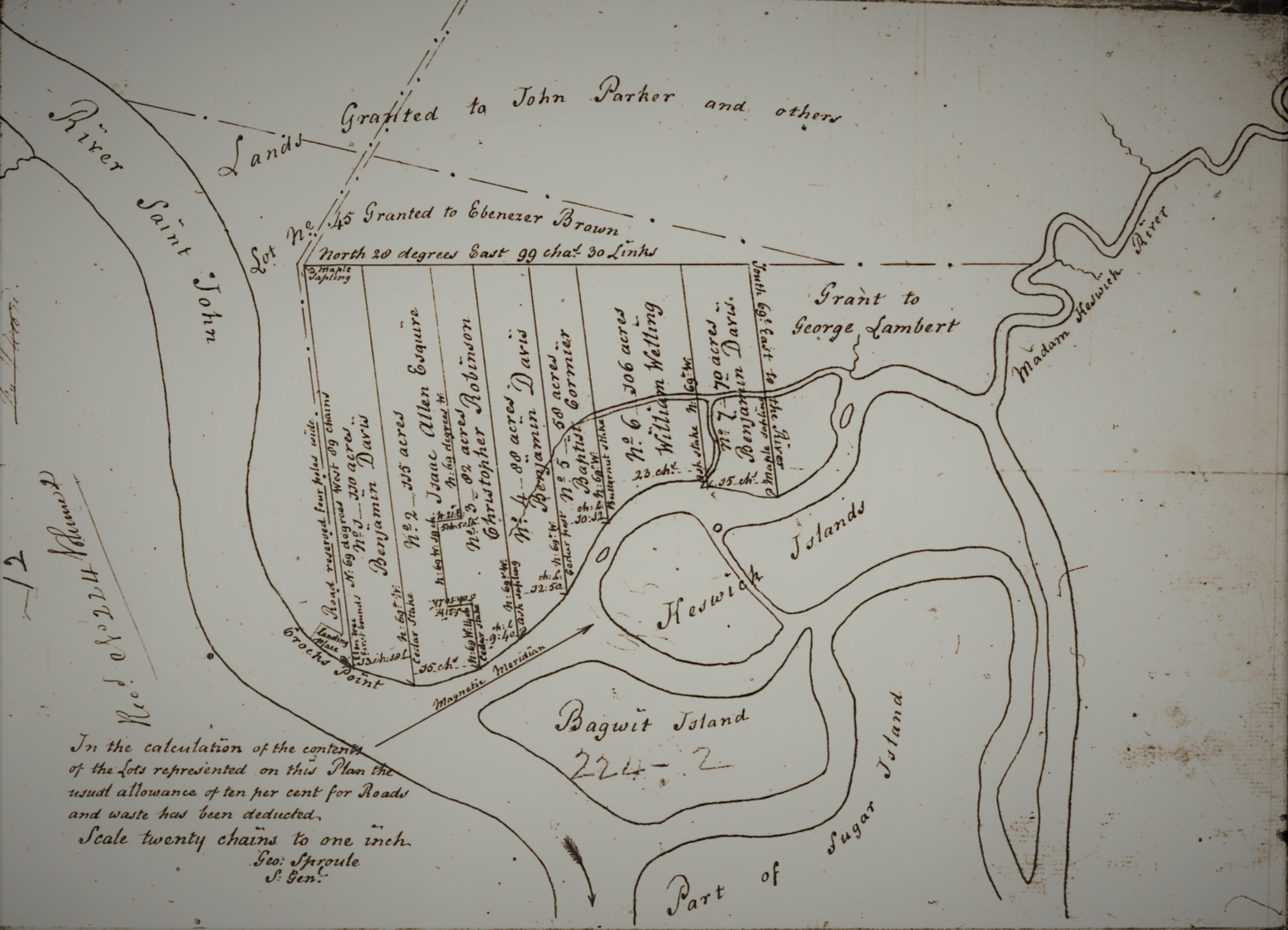

(p. 12, RS686, Provincial Archives of New Brunswick)

In a world where borders were measured in increments such as “five chains from the small butternut tree” or described as “bounded by William McRaw’s property,” exact latitudes and longitudes are difficult to map with precision, particularly when the landscape has changed greatly due to hundreds of years of agriculture and waves of settlers from various cultural backgrounds. As well, the spelling of place names was far from standardized in the eighteenth and early nineteenth century. For example, Northumberland County is particularly challenging when locating place names due to the prevalence of both indigenous and Francophone names, modified through Anglicization.

Place Names from Early Northumberland County Court Records

|

Early Nineteenth Century Version |

Modern Name |

|

Bay Devin/ Bay Devon |

Bay du Vin |

|

Niguac/ Negawaak |

Neguac |

|

Rushebucto |

Richibucto |

|

Buctush |

Bouctouche |

|

Rustigouche |

Restigouche |

|

Shediack |

Shediac |

|

Nepissiquet River |

Nepisguit River |

|

Point Aux Car |

Point aux Carr |

The Case of Scudawabeskeck Creek

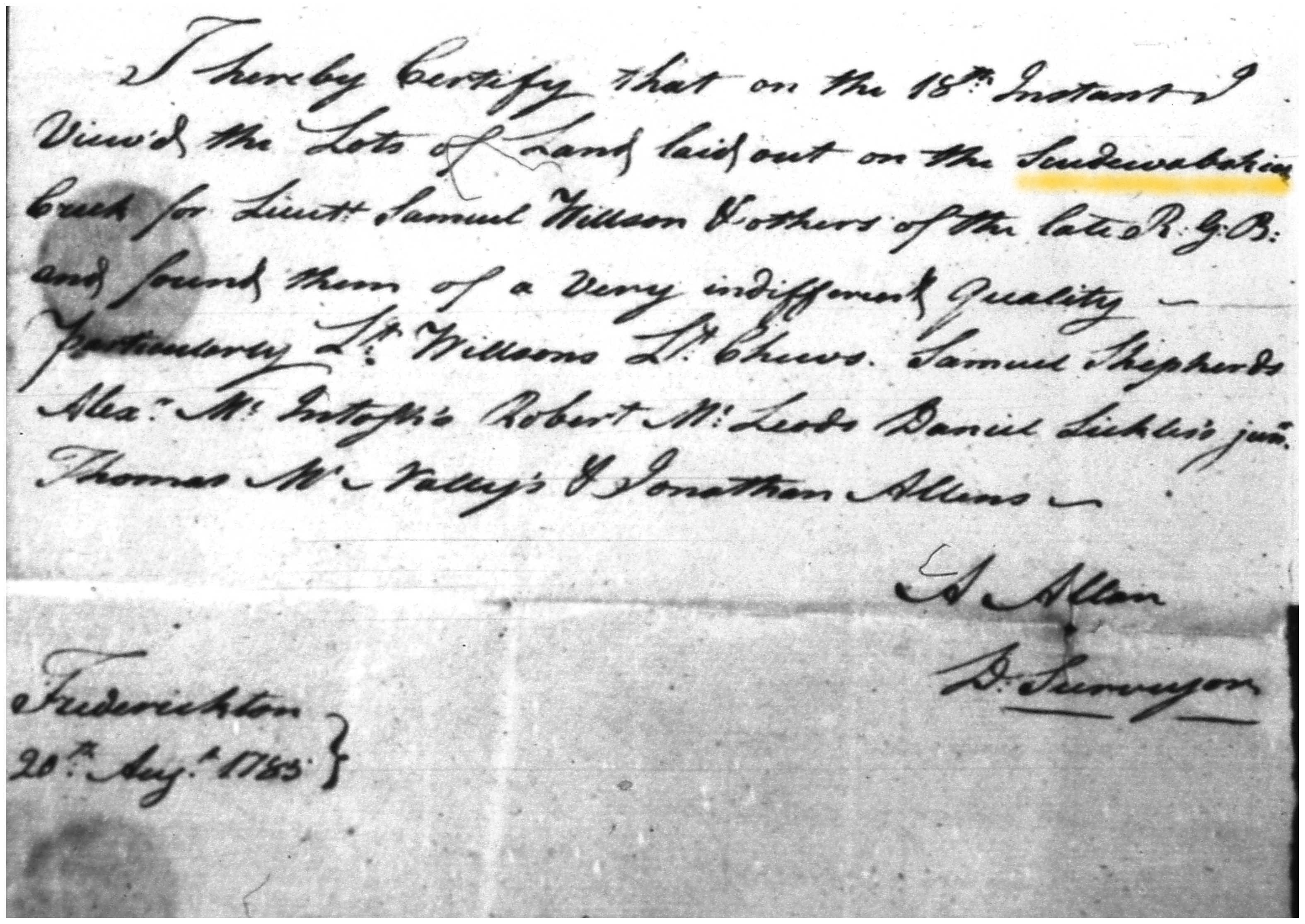

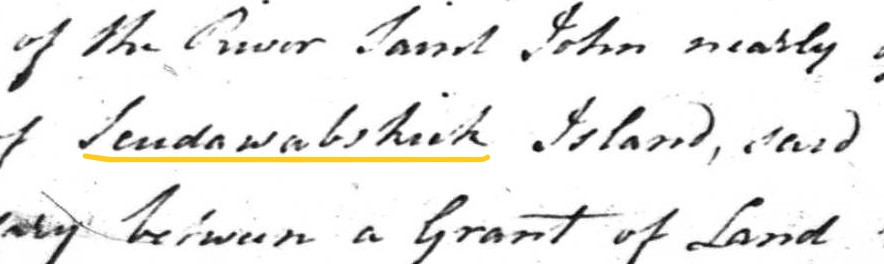

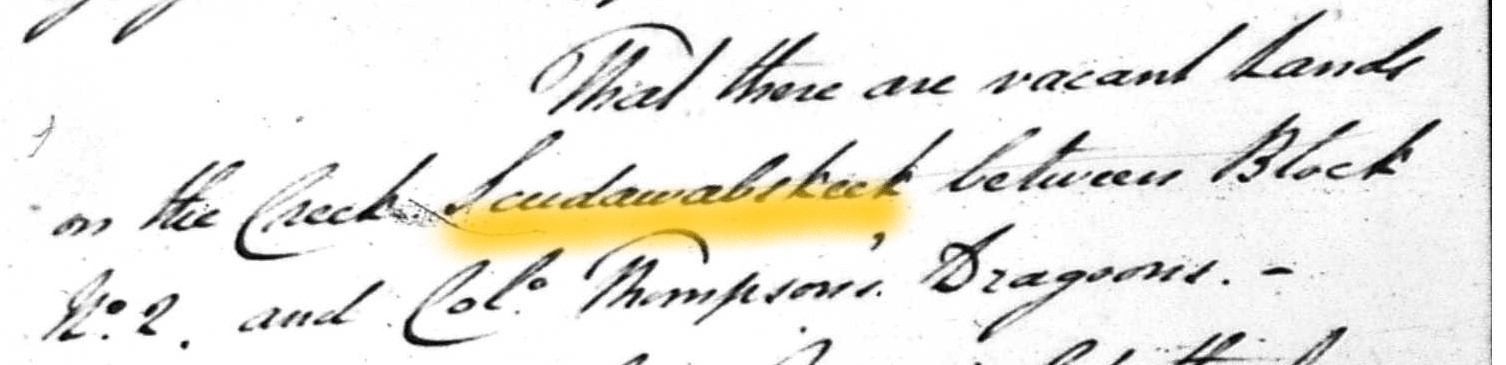

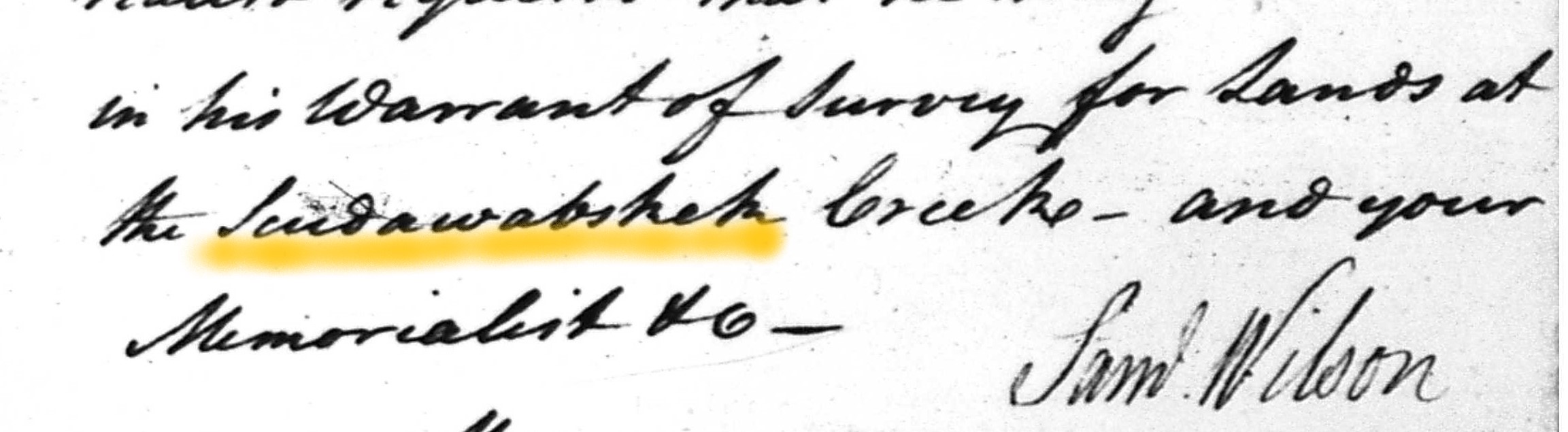

One particular place name caused our staff extreme consternation: the “Scudawabeskeck” Creek on which American Revolutionary veteran Lt. Samuel Richard Wilson had requested lands to be surveyed for a small number of the Royal Garrison Battalion who had chosen to settle in New Brunswick. A few clues offered possibilities for the locale of the mysterious body of water such as the names of regiments and grantees adjacent to the surveyed land on the Creek. The people of the period seemed to all innately know where the waterway was found, but it is not evident to a modern reader. The name of the creek is recorded variously as “Scudawabsheck”, “Scudawabekeek,” and “Scudawabskek”.

(New Brunswick, Surveyor General, Land Petitions: 1783-1834, The Loyalist Collection)

These were colonial versions of the original Wolastoqiyik name “Eskootawopskek,” later called “Scoodewapscook” or “Skoodewabskook” for the waterway (and also community) which now known as Longs Creek after loyalist Abraham Long. There was also an island (now flooded due the construction downstream of the Mactaquac Dam) which was renamed “Wheeler’s Island”, but originally called Scoodewapscook Island and mentioned in the colonial documents. All these clues and documents came into place to allow the discovery of a location of the mysterious creek.

In the end, Wilson and his compatriots did not find the land on Longs Creek and New Market suitable for their habitation and asked for land in other locations; Wilson ending up with a plot directly across from the mouth of Longs Creek on the opposite side of the St. John River.

New Brunswick can be an especially difficult subject when searching for historical locations because of the reformation and additions of counties and geographic changes. For instance, the Madawaska region in the northwest of the province was originally part of York County. Geographically, the construction of the Mactaquac Dam leading to the disappearance of Bear Island (among other islands) from which the community still located on the St. John River’s shore draws its name. Many other regions outside of New Brunswick have also undergone geographic shifts in the past two hundred years.

Where in the World is That Loyalist?

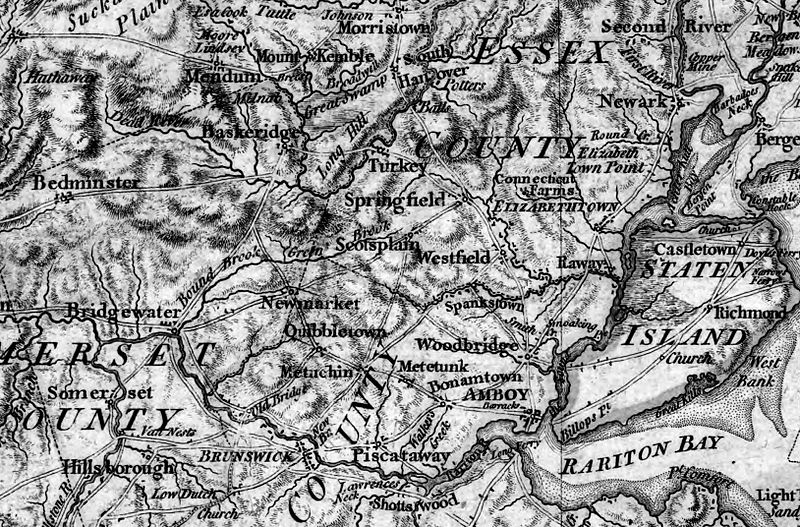

When delving into the origins and military careers of loyalists during the American Revolution, American place names can also present a significant test. Maps of New York and New Jersey have altered since the time of the Revolution, whether through community amalgamation or renaming. Many locations in and around New York City were important gathering points for loyalist and British regiments including “Lloyd’s Neck” (now Lloyd Harbour, Long Island), Paulus Hook (sometimes spelled “Powles” and currently a community in Jersey City, New Jersey), and Yellow Hook (now known as Bay Ridge, New York City). In some cases, the location of a loyalist’s original home, where they were stationed during the war, and their place of settlement must all be researched and verified in order to place them on a present-day map.

(William Faden [Public domain], via Wikimedia Commons)

By observing the change of place names and locations, we can see the rise and fall of communities as well as shifts in the environment. Although technology offers new way to present and analyze historical data, detailed research to confirm and clarify data cannot be replaced.

Recommended Sources:

Place Names of Atlantic Canada by William B. Hamilton

Place Names of New Brunswick, Provincial Archives of New Brunswick website

Leah Grandy holds a PhD in History and works as a Microforms Assistant at the Harriet Irving Library.

Add new comment