Anthony Casteel’s Account of Scalping Proclamations in Colonial Nova Scotia

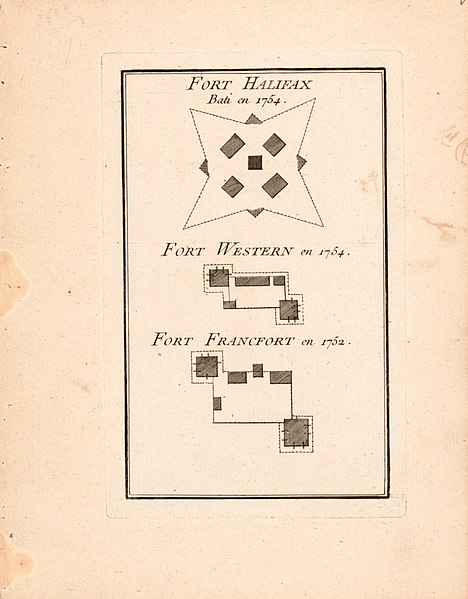

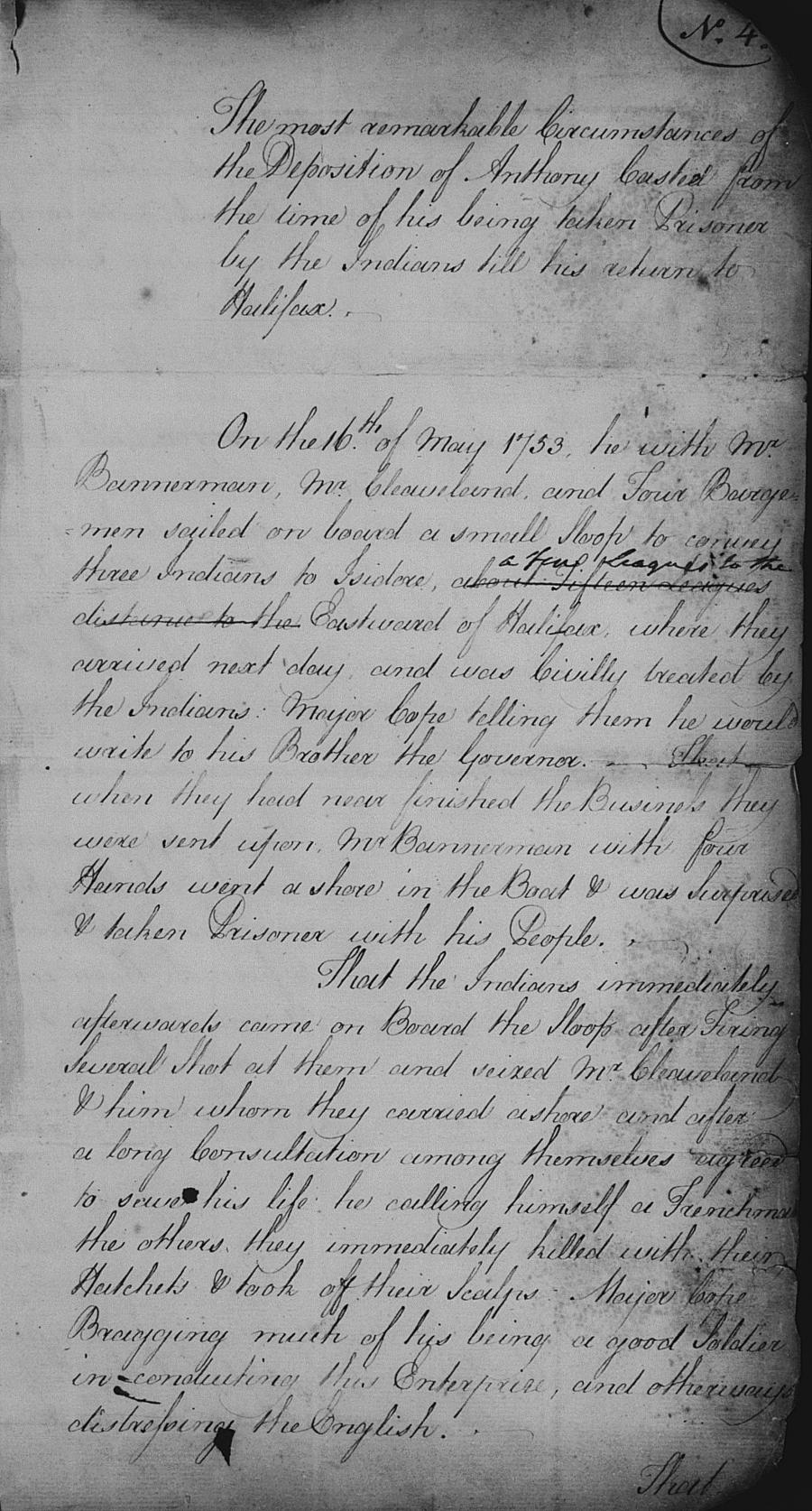

In 1753, English linguist Anthony Casteel, along with his crew, were taken hostage by Mi’kmaq warriors in Jeddore, Nova Scotia between the months of May and June. Casteel left Halifax, presumably from the town fort, to negotiate with neighbouring Mi’kmaq leaders.

However, during this time, regional hostilities escalated among the English, French, Indigenous, and Acadian parties which problematized Casteel’s presence in Mi’kmaq territory. These tensions were the result of a variety of factors, including French puppeteering of Mi’kmaq warriors against Britain’s imperial presence; English expansionist and settlement efforts on Mi’kmaq territory; and lastly, the intensification of English and French scalping bounties. Casteel noted that the aggression towards himself and the later death of his crew transpired as a result of a recent confrontation in which two English men, James Grace and John Conner, had stolen "forty barrels of provisions” from the Mi’kmaq community which was “given to them by the [English] Gov[ernor]."

Suffering a shipwreck soon after their theft, Grace and Conner were found "drenched with water, [and] destitute of everything." They were then taken in by the Mi’kmaq and "cherished, with kindly entertainment." Upon their first opportunity, Grace and Conner killed three women, two children (one an infant) and two men. The Englishmen arrived in Halifax on April 15 with six Mi’kmaq scalps "to claim the Wages of the atrocious deed." This event had occurred one month before Casteel's capture, and so the ensuing hostilities between the English and Mi’kmaq arose from Grace and Conner’s transgression.

Casteel was the sole survivor of his crew’s capture by Mi’kmaq warriors―owing to his false claim that he was a French citizen, and not English. His fluency as a translator aided in his disguise, as well as a fabricated backstory of being "Taken in a French vessel in the War” of Father Le Loutre―which explained his presence aboard the English vessel. Shortly after their capture, Casteel's crew (Captain Baunerman, Samuel Cleveland, and four bargemen) were killed and scalped by Mi’kmaq warriors. In his deposition, Casteel recalled that the Mi’kmaq Chief later said to Casteel that he was fortunate to be a Frenchman otherwise he too would have been killed. The Chief expressed his surprise that the "English began first: They had done no harm for a long time" but the "killing their people [the Mi’kmaq]" would be met with retaliation and an escalation in warring tactics to match the atrocities of the English. This escalation in warfare was owing to the financial incentive of the scalping bounties, in which English officials offered a monetary ‘reward’ for each Mi’kmaq scalp claimed. The French also issued bounties for English scalps to prevent further imperial interference in the region. It is clear that the Mi’kmaq and Acadian communities were caught in the middle of a colonial power struggle between the French and British empires.

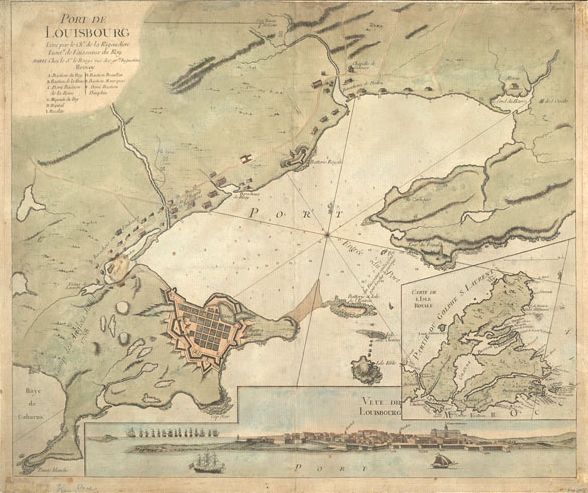

Casteel was eventually released after having a benefactor, James Morris, pay a ransom of 300 livres (pounds) for his life. Once out of danger, Casteel revealed to the French Governor that he was an Englishman upon his arrival at the Fortress of Louisbourg. Casteel was later permitted transport to the English stronghold of Halifax after an intense investigation into his true country of birth. It is interesting that Casteel adopted a French identity, as English nationalistic rhetoric characterized the French in derogatory language. Casteel’s disguise, although saving his life, required a momentary abandonment or betrayal of his national identity of Protestantism (as the French practiced Catholicism), despite his claim that he would “sooner be cut to pieces than stay away from my own country people and my family.” Casteel’s case demonstrates the malleability of religious and national identity to prioritize the welfare of the individual.

Instances of scalping were still prominent six years later in the Siege of Quebec, as witnessed by Edward Coats. In his personal journal, Coats writes that on July 23, 1759, the “Canadians and Indians” continued to Scalp every person who “[fell] into their hands” during the battle. Coats reveals that British troops were ordered by King George II of England on July 4 to “Carry on the War in this Country with the utmost Lenity, that he expects the troops under his Command will follow his Example that the Inhuman Practice of Scalping either by Indians or others may be put a stop to.” This demonstrates that Cornwallis’s 1747 scalping bounty was characterized as a necessity to settle Halifax and the surrounding area, while its practice by Indigenous warriors was seen as “inhuman” and stood in contrast to the “honourable” military actions of the English. This goes to show that the British Empire issued scalping bounties to benefit their expansionist agenda in North America, but demonized its implementation by Indigenous groups and others.

Historical context to Scalping Proclamations

Scalping bounties which targeted Indigenous inhabitants of North America were first issued by British colonial officials in the early-seventeenth and eighteenth-century, and were enacted in Acadia―a colony of New France which historically comprised the Maritime Provinces, eastern Quebec, and a portion of Maine―and northeastern American colonies. The earliest scalping bounties were issued in New England during the Susquehannock War (1675–77), and later during King William’s War (1688–97). In 1696, the Massachusetts General Court revived the anti-Indigenous legislation which encouraged white citizens to form companies, or private armies, to carry out acts of legal violence against Mi’kmaq men, women, and children and to be financially compensated upon the presentation of an “Indian” scalp. This bounty sought to disrupt the alliance between the Mi’kmaq and Acadian communities who the English believed were united under the banner of French imperialism and it, therefore, posed a threat to British supremacy in Atlantic Canada. The Mi’kmaq and Acadian parties were irrevocably affiliated with French imperialism through a blanket association with the warring operations of neighbouring Indigenous communities and also French privateering activities in the region. This legislation demonstrates that scalping proclamations issued by colonial parties were well established in the region of Maine and the Maritime colonies decades before Governor Edward Cornwallis’ genocidal declaration of the 1749 Scalping Proclamation in order to settle the land surrounding the English stronghold of Halifax in Nova Scotia.

Zoe Louise Jackson is a student assistant for the Microforms Unit at the Harriet Irving Library. She is currently in her last year of her Bachelor of Arts degree at UNB in History Honours.

SUBJECTS: scalping proclamations, Anthony Casteel, Edward Coats, Siege of Quebec, Edward Cornwallis, Acadian, indigenous peoples, First Nations, imperialism

Primary Sources –The Loyalist Collection

Anthony Casteel, “The most remarkable circumstances of the Deposition of Anthony Casteel from the time of his being taken Prisoner by the Indians till his return to Halifax,” Nova Scotia Legislative Council, Journals: 1758―1835.

Edward Coats, “A Private Journal of the Siege of Quebec,” Journal of the Siege of Quebec: 16 February 1759―18 September 1759.

Select Secondary Sources

Geoffrey Gilbert Plank, An Unsettled Conquest: The British Campaign against the Peoples of Acadia, (Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press, 2001).

__________________, "The Changing Country of Anthony Casteel: Language, Religion, Geography, Political Loyalty, and Nationality in Mid-Eighteenth Century Nova Scotia," Studies in Eighteenth-Century Culture 27 (1998): 53-74.

Add new comment