- Submitted on

- 0 comments

Our first post on palaeography generated a lot of interest and discussion (thank you, readers!), so we decided to create another post with even more background, tips, examples, and help for those trying to interpret historical cursive writing from the British Atlantic World.

(Public domain via Wikimedia Commons)

Some History of Cursive Writing

Early, British cursive, common by the fourteenth century, is termed Anglicana script, but also known as charter hand or court hand. Secretary hand followed, and was popularized in book production because of its rounder, quicker strokes which facilitated the copying process. Cursive comes from the root Latin word curo, meaning “run”, as the pen was kept on the paper, thus increasing speed.

During the Early Modern period, most writers could use multiple hands, or styles of writing. Different hands became associated with branches of the English courts such as Chancery, Exchequer, and King’s Bench. Iron gall ink or carbon (soot) were the common writing mediums, used in combination with quill pens (most often from goose, swan, and turkey feathers), which necessitated a pen knife for sharpening. Popular writing surfaces were rag paper—which was problematic because it was uneven, absorbent, and needed to be treated with size made from hooves and skin of animal, and vellum—which was greasy and needed to be used in conjunction with pounce (usually powdered pumice or cuttle-fish bone), all of which were quite expensive.

The Document as a Physical Object

It is important to remember that each document we examine also exists as a physical object, which should be taken into consideration during a document analysis.

To start thinking about a document as a physical object, ask the questions:

- Where did the writing surface itself come from?

- Is this an original or copy?

- Have there been insertions or excisions of text?

General Factors Affecting Writing

Writing differs from writer to writer, but it is important to note that there can be huge variations in style regionally and culturally. Variety is also demonstrated in speed of writing, i.e. whether the writer was working quickly or slowly. Some immediate and physical and mental factors which can shape writing include:

- The health of writer and injuries

- The writer’s care and concentration levels

- The age of writer

- Fatigue

- The mental condition of writer and stress

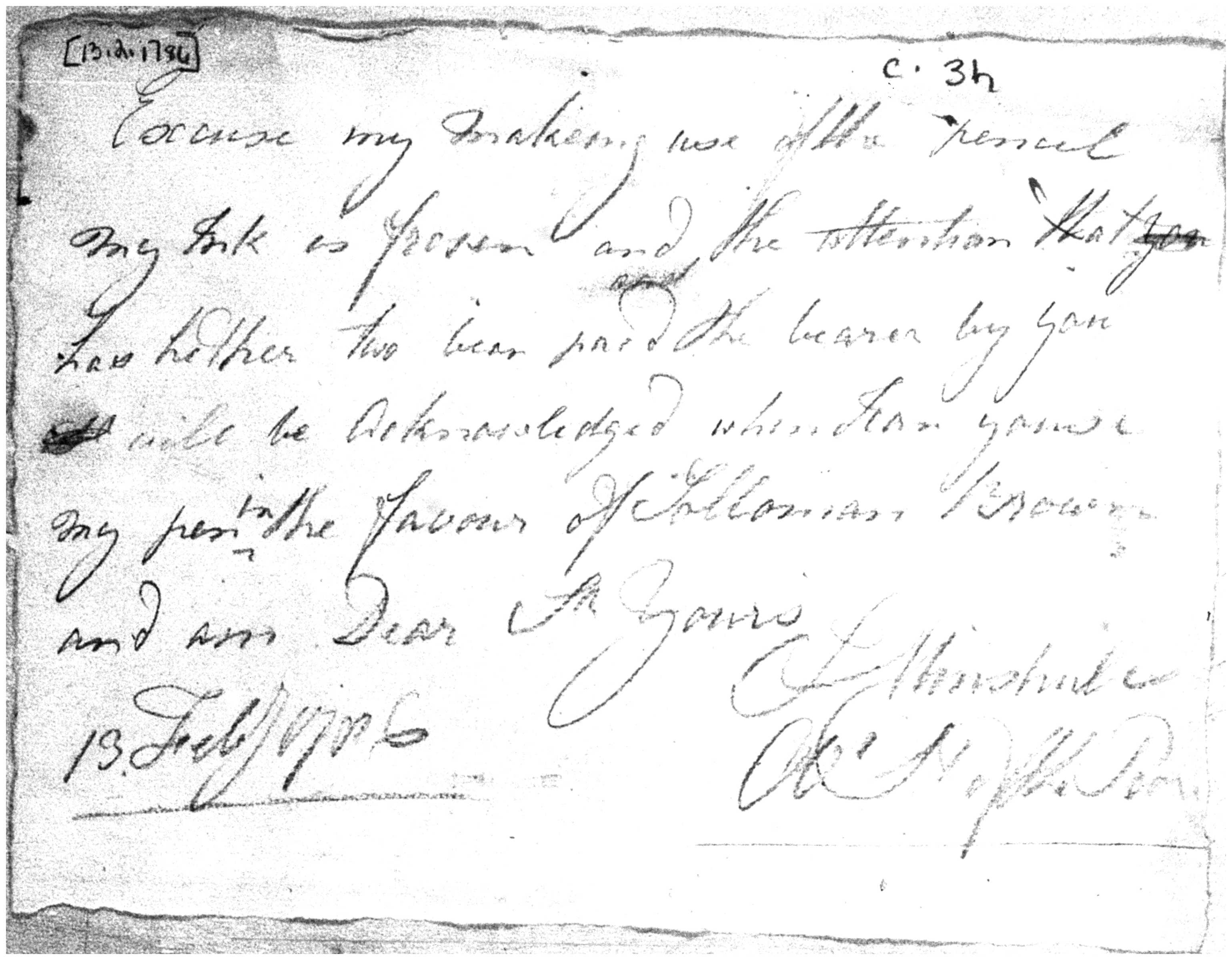

- The influence of substances such as drugs and alcohol

- Writing conditions (e.g. battlefield, in a carriage, temperature)

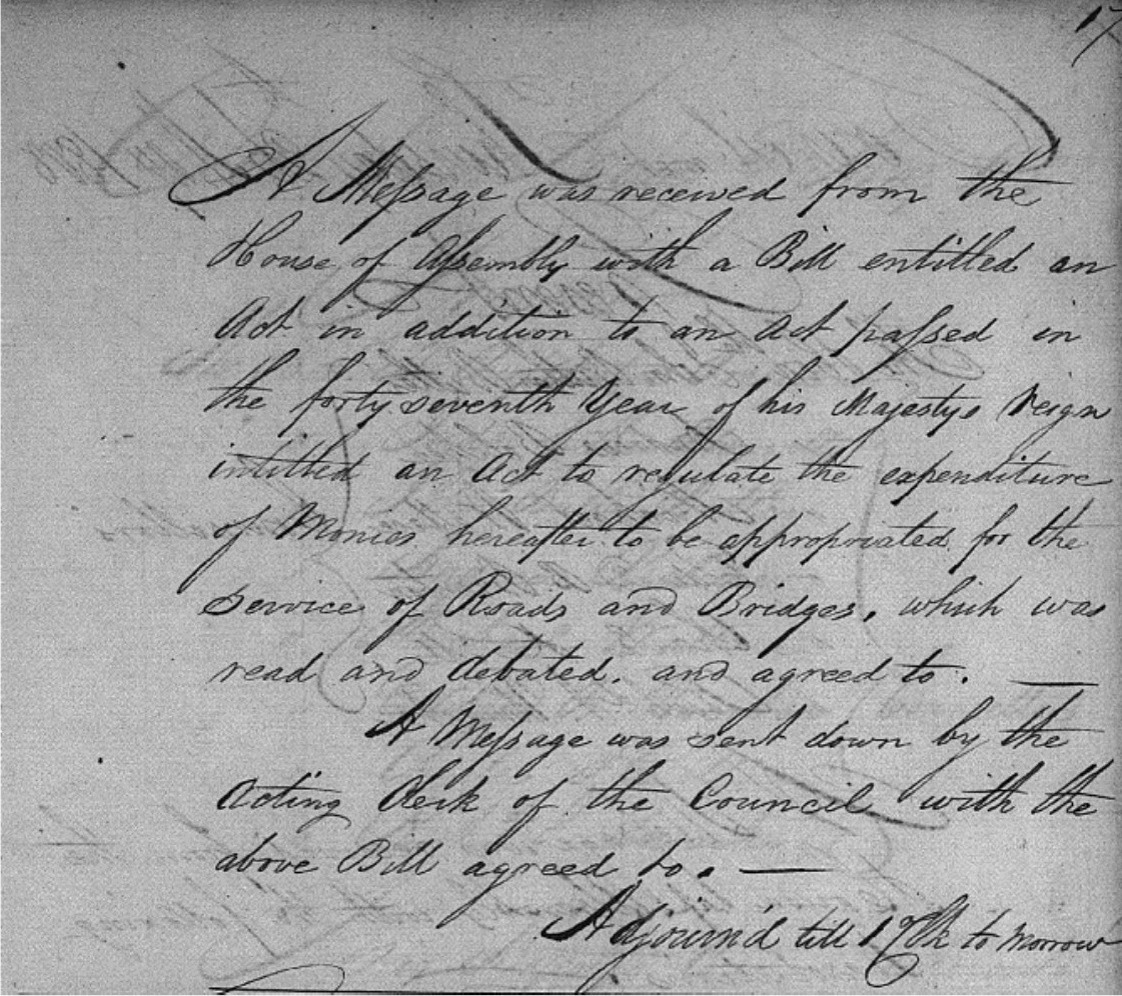

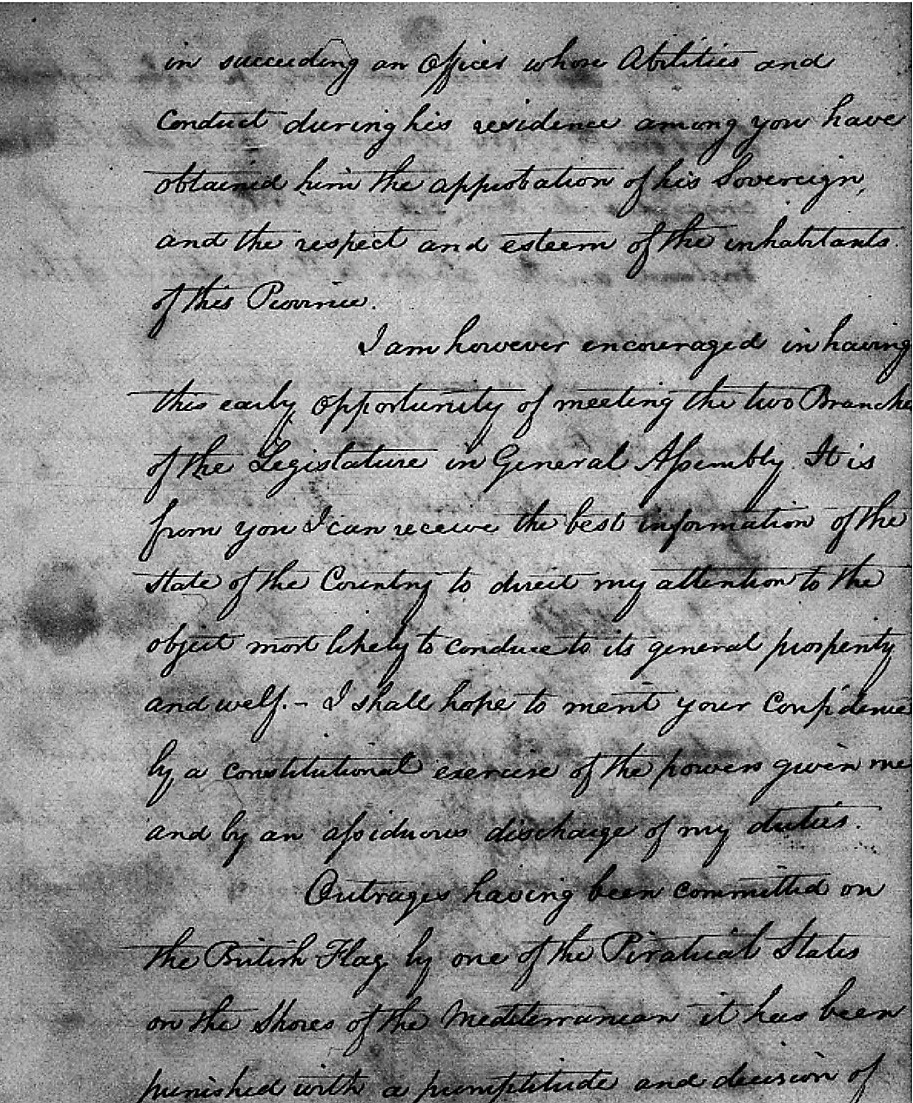

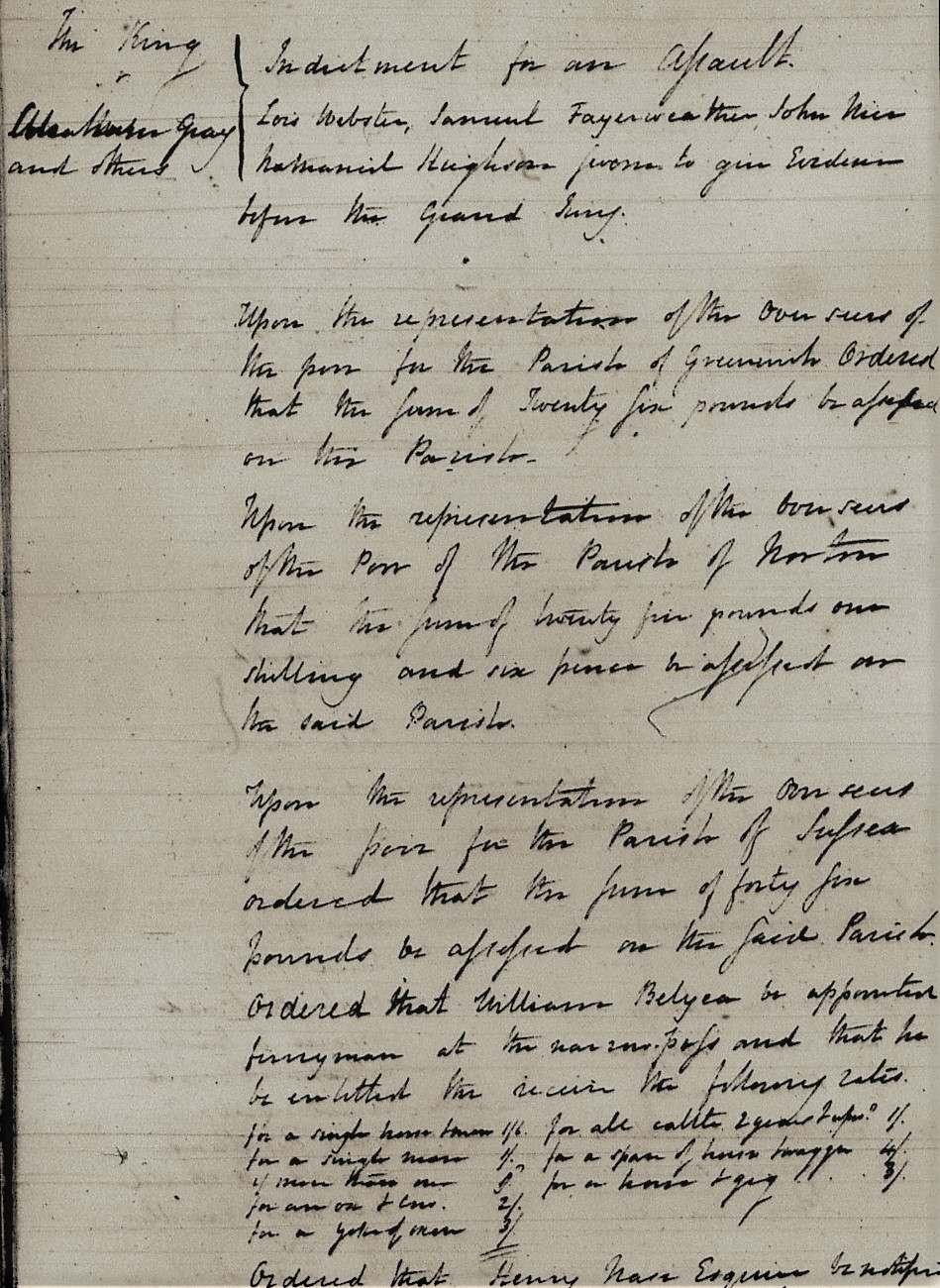

Note: All writing samples featured in this post are drawn from The Loyalist Collection.

Next week: More Palaeography Basics, Part 2

Leah Grandy holds a PhD in History and works as a Microforms Assistant at the Harriet Irving Library.

Add new comment